The Historical Significance of O'Connorville

Three Rivers District Council, Herts

Heronsgate Conservation Area Appraisal 2012 (pdf) Pp. 5-6

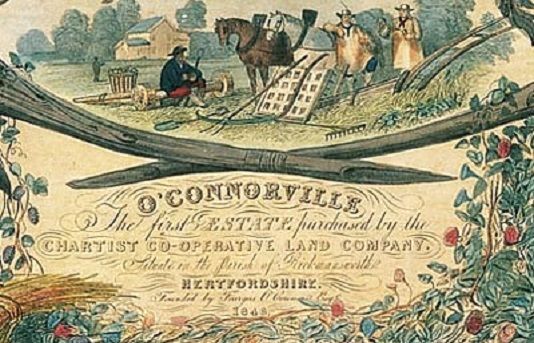

2.11 The story of the original Heronsgate settlement concerns one Chartist particularly, Feargus O’Connor. O’Connor was a man of contradictions. A brilliant man, Irish MP and Barrister, an intellectual who genuinely empathised with the plight of working class people; a thinker who was also a man of action. He became one of the leading and most famous members of the Chartist movement and, controversially, set up the Chartist Co-operative Land Society (or Company).

2.12 The Company had two main aims, the first was to liberate the working man and transport him and his family from the grim conditions of the mill, mine and factory to a life of self-sufficiency, subservient to no master and a healthy life in the country-side away from the polluted industrial cities. The second aim was to realise one of the main Chartist principles, that of universal suffrage – one man, one vote. By providing families with their own plot of land and their own house they would become landowners with the right to vote.

2.13 The way in which O’Connor set about this was to create a lottery; working men from all over the north and the midlands bought tickets (or shares) and there were great draws to see who had won the chance of a new life. The draws were very dramatic and highly charged events with the prize offering not wealth but health and freedom from the factory floor.

2.14 The glimpse of such an idyll was irresistible and thousands of working people saved 3d a week to purchase a £2.10s.0d share. One share gave you a chance of a 2 acre plot, 1½ shares a 3 acre plot, with 2 shares for the larger 4 acre plots. The financial plan was that £5,000 would be raised from 2,000 shares allowing the purchase of 120 acres (at £18.15s.0d/acre) with £2,250 to build cottage and buy stock.

2.15 Heronsgate Farm (103 acres) was bought by O’Connor for £1,860 (at a time when the Land Company had £8,081), and he personally supervised the laying out of the plots, the construction of the roads and of the houses. This was a major achievement as nothing in his life or upbringing gave him the practical skills needed to plan and construct the infrastructure and to design houses and employ builders to construct them. Appendix 2 , Historic Map 1872-1891 depicts Heronsgate otherwise referred to as O’Connorville.

2.16 The roads were to be nine feet wide, wide enough for a horse and cart. All the roads were named after industrial towns to give the new residents a sense of familiarity in these strange surroundings. A short access road (Stockport Road) left Long Lane following the line of the former farm access track. At right angles to this, a long road (Nottingham Road) bisected the site allowing space for the larger 4-5 acre plots to the south-west.

2.17 The area to the north-east was itself bisected by another long road (Halifax Road) which had the smaller 2 and 3 acre plots along it. It was not the most efficient layout as Nottingham Road had houses on both sides of it but Halifax Road had cottages only on the north-east side. The determining factor though was the variety of plot sizes with access to each plot. At the northwest end of Nottingham Road it turns sharp left and becomes Bradford Road.

2.18 The houses were built so that each related directly to its plot. O’Connor could have saved money by grouping the dwellings together but the relationship with the land was of over-arching importance. He did however save some money by building 18 of the houses as semi-detached pairs. The remainder were single storey dwellings and a variety of some individual houses making up the total of 35, the remaining plot being occupied by the school.

2.19 The plans were relatively simple. The semi-detached pairs had an entrance into a parlour in the side wing with the living room in the main part and a staircase up to the bedrooms. The cottages had a central entrance into the living room with the kitchen off to one side and a bedroom on the other.

2.20 Externally all were simply rendered and had slate roofs. The semi-detached houses and cottages had a central pedimented gable with a stylised version of the Charter – a tablet with two tabs. Some properties were provided with outbuildings for animals and crops, others were left for the first settlers to build what they required.

2.21 Following the development of Heronsgate, O’Connor proceeded quickly with the development of four other Chartist settlements at Dodford (Worcestershire), at Minster Lovell (Oxfordshire), at Snig’s End (Gloucestershire) and at Lowbands (Gloucestershire). The design of each of these settlements was different but the architectural styles (although not the materials used) were common to each settlement, as were the narrow lanes. There are close bonds between these five settlements although they are located many miles from each other.

2.22 A New Era

2.23 Things started to go wrong quickly. Many of the new settlers found coping with subsistence farming very difficult. Many abandoned the struggle. In 1847 when there was a very hard winter, rents were not being paid and contributions to the Company were falling. The main problem was that Feargus remained the owner of the land. He failed to get the Company registered either as Friendly Society with Charitable status or as a Land Bank company.

2.24 In both cases the problem was the same. The scheme was a Lottery and most contributors did not benefit at all, either by way of charitable relief or as a return on investment. In fairness to O’Connor, a Parliamentary Commission made it clear that, while the enterprise was illegal, it was not operating for the benefit of Feargus; quite the opposite, the Company in fact owed him money.

2.25 The Company had though to be wound up, despite the fact that Feargus, in receipt of no rents, went on building, went on juggling finances – while slowly going mad. He died in 1855 and had a hero’s funeral with tens of thousands following the funeral procession to Kensall Green Cemetery. It was said to be the last great Chartist demonstration. A statue was later erected in Nottingham, paid for by public subscription.

2.26 Meanwhile, the Estates were administered by the Court of Chancery and tenants made agreements to pay rent to seek entitlement to ownership, or properties were sold on at auction; a gradual process not fully complete until the 20th century as evidenced by the continuing payment of “Farm Rents”.

2.27 During this time, the concept of subsistence farming was superseded but Heronsgate did not decline. Those settlers who remained were people who had skills to offer the local communities, for instance cobblers, blacksmiths and carpenters. Small work-shops developed at each of the Chartist settlements.

2.28 But, there was a change of character as some people came to realise that it was possible to live in a pleasant environment at Heronsgate and, as transport improved, travel to work in local towns and London. As part of this process most of the original buildings were altered, many of the plots were sub-divided and new dwellings were erected. This growth was largely unplanned and mainly took place in the first half of the twentieth century.

2.29 The only alteration in the road layout has been the introduction of the cul-de-sac known as Cherry Tree Road, this and the houses were built in the inter-war years. Otherwise the layout of roads remains as set out by Feargus O’Connor in 1846.

2.30 Not only does the pattern of roads survive, but they are of the same (horse and cart) width, and now have well established hedgerows giving an even narrower feel to the road. They are very much country lanes despite their straightness. The hedgerows and the lanes are of importance to the character of the area. Appendix 3 details the original hedgerow boundaries.