Please Note that this article is the copyright of ©Ray Stroud 2018 and may not be copied, printed or used in any way without the permission of the author

In search of Jenkin Morgan

Ray Stroud recalls Ivor Wilks speaking at Newport in November 1989 “with such enthusiasm”

Wilks’ vivid description of the role played by the Pill milkman, Jenkin Morgan, “laid down a marker in my imagination”

Ray describes how this chimed with his own ‘detective’ approach to teaching and inspired the excursions he made into the archives

In search of Jenkin Morgan

In the early 1980s, history documentaries changed forever. To be brutally honest, history on the television back then was just plain boring. Other than a couple of outstanding programmes by Gwyn Alf Williams, my strongest memory is that of A.J. P. Taylor, standing virtually motionless, delivering unscripted talks to fixed cameras.

The new kid on the block was Michael Wood. In March 1981, the Radio Times reviewed the second series of In Search of the Dark Ages. It commented that this 32 year-old ‘history man’ glowed with ‘exuberance, charm and delight’.

Wood’s presentation of history was radically different. Forensically scouring the British landscape for clues, his style was new and innovative. He jumped out of helicopters draped in a sheepskin flying jacket, ‘in search of ’Alfred the Great, Athelstan and Eric Bloodaxe. Suddenly, these figures from the distant past were vividly resurrected, and commentators heaped praise on Wood for the infectious enthusiasm of this ‘new trendy BBC wonder-boy’. In the years that followed he came to make the phrase ‘in search of’ his own.

At the time, I was studying for a Postgraduate Certificate of Education (PGCE) and, without doubt, Wood influenced my approach to teaching history. It became important that history was seen as being exciting – even in a secondary school! As a ‘Newport boy’ I had always had a fascination with Chartism - as a kid I vividly remember pushing my fingers through the holes in the portico of the Westgate Hotel. It’s glaringly obvious to say that Chartism and the Dark Ages have very little in common. But the ‘New History’ of the 1980s was all about detective work. It was a template rolled out to all periods of history. Pupils were encouraged to look for clues, and teaching using source materials was very much in vogue. I had also been taught at Swansea University by David J. V. Jones and, in 1985, his pioneering book, the Last Rising came to represent a major milestone in my ongoing search for Newport’s hidden past.

Then, on 1st November 1989, Ivor Wilks gave a lecture at the Westgate Hotel. His book, South Wales and the Rising of 1839 had been published just five years earlier. He spoke with such enthusiasm about the background to the Rising and of the events that had elicited such a swift reaction from the State. As he described the role of the Pill milkman, Jenkin Morgan, he laid down a marker in my imagination. Perhaps it was the notion of a radical Chartist, hell bent on political revolution, returning home within six hours to deliver milk on the streets of Pill that struck a chord with me. From that point, I was in search of Jenkin Morgan.

An early nineteenth-century milkman.

By 1839, Morgan was already a prosperous milkman, tallow chandler and soap boiler; he was also ‘in possession of three houses, seven fine milk cows and other property’. After being apprehended and put on trial, he complained that his landlord, Thomas Prothero, had taken possession of his hay rick valued at £95. On the night of 16th January 1840, this rick was set on fire in an act of political revenge. It was no coincidence that this was the day when capital sentences had been passed on the Chartists at Monmouth. Despite offering a reward of £100 and petitioning the Home Secretary, the case was never solved, while Morgan continued to retain a strong sense of injustice throughout his years of imprisonment at the Millbank Penitentiary.

By 1839, a new radical landscape had emerged in the working-class districts of Newport and in Pillgwenlly in particular. This groundswell of popular support fed directly into a network of underground Chartist cells located throughout South Wales. Chartist lodges provided an organisational framework through numerous public houses and beer shops, and constituted a prominent threat to the Establishment. Indeed, by the spring of 1839, the authorities seem to have detected a change in the nature of both the crowd and the speeches at radical meetings in Newport. Processions tended to begin in the streets of Pill and there were real fears that navvies, canal boatmen, the unemployed and even criminals, were beginning to be affected by Chartist propaganda. One such street in Pillgwenlly was Quay Street, what today has become Church Street, and this was home to Jenkin Morgan

.

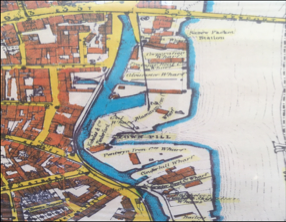

A section of the Tithe Map of 1845, showing the district of Pillgwenlly.

Morgan was, undoubtedly, a radical Chartist. He was a devoted disciple of Henry Vincent. He even spoke in the same biblical language as Vincent. In an argument with Maria Harper in April 1839, he had confidently predicted that ‘every one that would not join the Chartists’ would be ‘mown down like grass’. We also know from the records that Jenkin Morgan played an active role in the preparations for the Rising. He spoke of simultaneous risings across the kingdom, and made reference to a plan to take over the Newport Union Workhouse and its arsenal, together with the home of the magistrate Lewis Edwards, who lived nearby at Brynhyfryd. Edwards was deeply unpopular for declaring public assemblies to be illegal, and had been marked down by Frost as an ‘enemy of the people’. Morgan even had prior knowledge that the town was to be invaded by hundreds of men through the Malpas, Stow, and Cwrt-y-Bella turnpikes, and believed that the soldiers would be surprised and disarmed.

Having anticipated this armed struggle, Jenkin Morgan became heavily involved in the clandestine manufacture of weapons in Pillgwenlly. The trial evidence provided by the blacksmith William Stephens, reveals the extent of arming and drilling in Monmouthshire in the months preceding the Rising. It seems that Stephens, who had his own smithy in New Street, was responsible for the production of some of these pikes. He testified that Morgan asked him to make him a sharp pike ten inches in length. It seems that John Gibby, a thirty year-old blacksmith employed at William Evans’ foundry, also manufactured a large number of the weapons used by the Chartists during the attack on the Westgate. In 1839, Gibby was living in Cross Street with his wife and three young children; a police search of his house after the Rising discovered drawings of pike heads together with sets of accounts, which covered a number of months. A basic pike cost 1s 6d and was often bought over three instalments of 6d each. This would seem to support Ivor Wilks’ claim that pike-making was already underway in Pill in the weeks after Vincent’s arrest in May 1839

.

A Chartist pike (Courtesy of Newport Museum and Art Gallery).

On the night of Sunday 3rd November, Jenkin Morgan and his men were positioned near Christchurch ready to discharge rockets. These were to act as a signal for the Newport Chartists to go into action. They then intended to take Parson Roberts and his family and ‘confine them in the Clock House’. Morgan also had orders from Charles Waters to seize Aaron Crossfield’s warehouse at Cinderhill Wharf, where there was ‘a great deal of gunpowder’. The aim was to use it to destroy the bridge over the River Usk. By the time the Chartists ‘from the hills’ arrived, however, it was daylight and the rockets were of little use. Ivor Wilks comments that, at 3 am, ‘the Pill Section went home, convinced that nothing would happen that night. At 6 am Jenkin Morgan was making his milk round’.

The location of Cinderhill Wharf.

He was seen that morning by John Lewis, the licensee of the Tredegar Arms in Pill and, unfortunately for Morgan, it was Lewis who recognised him again in Bristol some weeks later as he was taking a glass of beer at the Bunch of Grapes beer house. It seems that Morgan had booked a place at the Bush Inn for one of the London coaches on the afternoon of Thursday 21st November, at a cost of 18 shillings. By now there was a significant reward of £100 placed on his head, and he was being hunted by Constable Moses Scard, under orders from the Superintendent of the Newport police force, Edward Hopkins. Lewis, and two other Newport men, immediately sent for a policeman; Morgan was then arrested by Police Sergeant Phineas Sims in the kitchen of the beer house and, when confronted, gave his name as Morgan Jones. Lewis, however, as a Pillgwenlly man, was able to identify him. He was searched and charged at the police station house. Jenkin Morgan was found to have 8s 6d in cash, two neckerchiefs, a pocket book, a knife and a comb on his person. When the Bristol police visited the Bush Inn they found that he had no box or parcel with him. He told them that he had arrived the day before from Swansea, and had caught the steam packet from Cardiff to Bristol.

Trial and imprisonment were now ahead of him, and the consequences for Morgan were to prove life changing. In 1840, Millbank was the largest prison in London and was, effectively, a brick fortress. It represented an imposing and intimidating symbol of penal retribution. Of the seventy-three Chartists prisoners listed in HO 20/10 (those arrested between 1839 and 1840), fifteen were from South East Wales. I have also found a large collection of letters and petitions from John Lovell, Charles Walters and Jenkin Morgan in HO 18. All three men made a number of applications to be pardoned with no success.

.

By April 1844, Morgan was a broken man. He again wrote to the Secretary of State, Sir James Graham and ‘resolved never again to interfere with the political affairs of my country, either directly or indirectly’. He asked for a pardon so that he might, ‘be able to make a home for my wife and children before the winter sets’. On 10th May, both John Lovell and Jenkin Morgan received a free pardon from Queen Victoria for their ‘crimes’ of 1839. Soon, Samuel Etheridge informed the readers of the Northern Star that, ‘John Lovell and Jenkin Morgan, two of the Chartist prisoners tried at Monmouth, under the Special Commission … have arrived in Newport’. He added that, on arrival they were both ‘much shattered in constitutional health and strength, particularly Morgan, who is almost too feeble to walk alone’. Lovell arrived by the steam packet from Bristol on the morning of Thursday 16th May, while Morgan returned on Saturday 18th May 1844.

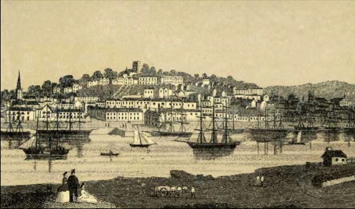

The site of the Bristol Wharf, Newport c. 1840.

Morgan was destitute, and pleaded with Feargus O’Connor for help. He described himself as ‘one of those unfortunate persons that have suffered four years and a half in solitary confinement, in that destruction of health and spirits, the Penitentiary, for the unfortunate Chartist movement of 1839’. O’Connor’s response in the Northern Star on 27th July reassured his fellow Chartists that, when he went to Wales, he would restore Morgan to his former position and that he would not, ‘remain a Chartist “scarecrow”, to be pointed at by Tom Phillips and Attorney Protheroe (sic)’.

The imagery provided by the scarecrow here is comparable to that of the Straw Man in “The Wizard of Oz”. His position is one of entrapment; he is tethered, static and powerless. It is easy to forget that Yip Harburg, who wrote Somewhere Over the Rainbow, also penned the haunting lyrics of Brother Can you Spare a Dime? A different century on a different continent, but the core issues would have been instantly recognisable to all Chartists – a reactionary government, hunger, unemployment and anger. Effectively then, Feargus O’Connor was acting as a sort of nineteenth-century Dorothy, someone who was exclusively equipped to release ‘Jenkin Morgan the scarecrow’ from his subjection to ridicule.

It seems that Jenkin Morgan eventually found lodgings with his brother, who was a farmer. We know from the trial records that he had a brother was called Evan. We know, too, that the Morgans were Glamorganshire farmers. On 21st December 1839, The Glamorgan, Monmouth & Brecon Gazette and Merthyr Guardian commented that, ‘Jenkin Morgan, cowman, of Pillgwenlly … was one of the Morgans of Landow, near Cowbridge’. There is some evidence to support this. I have found an Evan Morgan farming land near Llandow on the Tithe Map and the accompanying apportionment schedule. Yet, it is also possible that he relocated himself within the Pyle and Kenfig parishes. In 1844, Etheridge had commented that he had ‘gone into Glamorganshire where he has a brother, a farmer, living near Pyle’ and, on a letter sent from to Evan Morgan, his address is given as, ‘Cornelly, Pyle, Glamorgan, South Wales’.

A letter sent to Evan Morgan from Millbank (HO 18).

Without doubt, there is far more to find in the search for Jenkin Morgan. The historical footprints that he left, however, raise important questions about the organisation and planning of the Newport Rising. As a result, the role played by this Pill milkman sheds light, not only on the events of November 1839, but also on the mindset of the entire British Chartist Movement throughout the 1840s.

Ray Stroud, January 2018.

* The other names listed in HO 20/10 are: Wright Beatty; David Evans; Ishmael Evans; James Godwin; Thomas Kidley; David Lewis; Walter Meredith; William Price; William Thomas; William Williams.