Kennington Common:2018

Debate about the size of the crowd at the Chartist Meeting at Kennington Common on Monday 10 April 1848 in south London has surfaced at the two most recent Chartism Day conferences. At the time, Feargus O’Connor claimed an unacceptable figure of 300,000 but since 1982, David Goodway London Chartism 1838-48 (CUP) has held the field, at least amongst Chartist historians. He maintained that probably half that number crossed the Thames bridges and in his 2nd edition (2002, page 76) maintained 150,000 was ‘not unreasonable estimate of the support’.

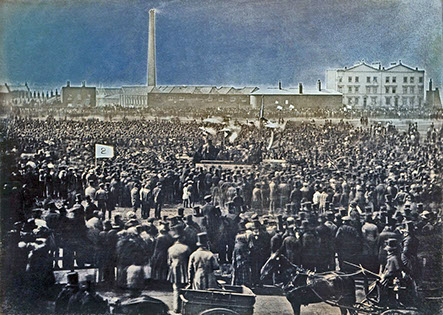

Last Year at Rickmansworth, Dave Steele (Warwick University) questioned the size of such estimates. He has been employing the latest photographic technology to examine and analyse the crowd as shown in the two Daguerretypes that survive from the camera work of William Kilburn. These are in the Royal Collections, purchased by Prince Albert.

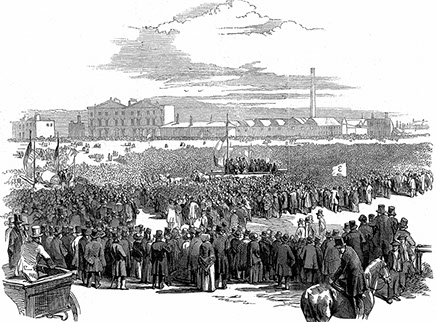

This year’s conference at UCL was followed by a visit to the Common (now since 1854, Kennington Park) There, we were met by members of the Kennington Chartist Project, which takes Chartism as an inspiration for engaging people today in political action. They have taken note of Dave Steele’s research and on their website talk of “tens of thousands of people gathered”. David Goodway was there, defending his position. Looking at the contemporary engraving (TUC Collection, London Metropolitan University) a figure of above 100,000 is surely plausible.

Paul Harman was there and he was intrigued by an equally important question – how could speakers like Feargus O’Connor effectively communicate with crowds of thousands? He points out -

Those at the 2018 Chartist Day visited Kennington Common where actor Tom Collins delivered Feargus O’Connor’s speech to a vastly smaller crowd. And he used a megaphone!

I’ve had an Equity card since 1963 but from the age of 11 had parts in school plays on an open-air stage and since then I have attended – and directed - many shows in outdoor settings. Some rules have applied since the ancient Greeks made sponsorship of new plays and attendance at theatre festivals a compulsory part of citizenship!

Rule One: get your audience as close as possible. A curved classical amphitheatre not only seats thousands tiered up in rows so all can see well but the enclosing shape is acoustically perfect so vocal sounds are received equally. The acting style also involved other means to reach across such huge spaces. Choruses danced and sang their text and actors sometimes wore masks with built in megaphones.

Rule Two: as Shakespeare’s smaller and cruder, but more efficient, wooden theatre proved, a solid background for the actor, a significantly raised platform and wooden surfaces to bounce your voice off gives you flexibility for a more nuanced delivery. That allowed playwrights to craft a more complex poetic language. But audience numbers were much smaller than in classical stone amphitheatres or open air events.

Rules Three to Ten: don’t make people to stand for a long time in an open field with the sun in their eyes listening to complex ideas while a stiff wind is blowing your voice back at you.

I’ve had two recent experiences of the Big Meeting at Durham. Both had too many speeches from a disparate range of people with very different styles of address. It is confusing and detail is soon forgotten. At both events the crowd was said to be over 100 thousand although more for Corbyn than for Milliband, certainly. In previous years, the principal guests and speakers sat on a wide low platform and amplification was minimal. 2018 featured a contemporary rock stage with vast banks of speakers and screens to enable those at the very back to hear and see the Beast of Bolsover in fiery close-up! It was technically better but not much more effective politically, in my view.

At Durham Miners Gala there is a great deal of extraneous noise to fight from the fairground, drinkers drinking, generators running in burger vans and families with small children having picnics. We can assume that Feargus O’Connor had little of that to contend with? There is also a generally held opinion that before the age of mass literacy, let alone TV and smart phones, most people lived in an oral culture and could therefore be expected to derive more from the spoken word than we can today. Apparently Shakespeare’s actors spoke very fast, but I think Bill’s fine words were often cut short to let people get to the pub or catch the last barge. We certainly very rarely play every word of the longest extant texts today.

However, from my own performances of some of Shakespeare’s language, I have come to respect the very careful shaping of the language to make it easy for the actor to deliver.

“Now is the Winter of our Discontent made Glorious Summer by this Son of York…” (The opening lines of Richard 111). ‘Now’ is a howling open diphthong, ‘is’, ’winter’, ‘discontent’ combine harsh thin sounds and staccato aggression, followed by the mocking cascade of ‘glorious summer’ and the hissing of ‘s’ sounds jammed together in ‘this – son’. Even spoken it sings. All the best rhetorical language does this.

At Durham, the booming tones of a Northern trade union leader got more a more fulsome crowd response than carefully crafted facts from a Shadow Cabinet member.

On Kennington Common that day in 1848 the speech for which we have an extant text had a very simple set of messages. The tone was sober and determined.

To begin with the closing words as we have them: “Go on, / conquering and to conquer, / until the People's Charter / has gloriously become / the law of the land!”

One can easily imagine a bold gesture to underline ‘Go on!’ The open ‘o’ vowels carry well and the concept ‘conquer’ is repeated to aid its capture by the ear. ‘Peoples Charter’ would be understood by all from the first shrill syllable. ‘Gloriously become’ is almost the same as in the Richard 111 line, and is a slow, tumbling filler before the easily recognisable and alliterative ‘law of the land’.

The opening line is similarly crafted for a powerful, clear delivery.

‘My children, / you were industriously told / that I would not be amongst you today. Well, / I / am / here.’ (Great cheering).

Standing high above the crowd on a wooden carriage which may have given extra resonance and a clear view for the audience – a vital part of hearing is seeing the body language – gives us clues as to how such ‘monster meetings’ may have worked. Laurence Olivier always called for ‘more light’, saying; “If they can’t see me they can’t hear me!”

In the end, standing in a crowd of fellow activists, even, or perhaps especially, among people you do not personally know, is a symbolic act with much more importance than being at a press conference or a lecture. I cannot now recall the substance of what most speakers had to say at the Durham Big Meeting. But I have a clear memory of how some speakers presented themselves and very little about others. And I knew in advance what Corbyn would say anyway, just as rock fans know all the words to all the songs – but they still travel hundreds of miles to hear them live.

O’Connor’s message was simple: ‘I am here but we are not going to march on Parliament’. Anyone at the event could grasp that. Those at the front would later retell their favourite details of the speech to friends and fellow activists back home. That is why big meetings work; they generate an emotional sense of ownership of the project.

©Paul Harman 2018