LES JAMES TALKING with TERRY FROST JONES (Part 1)

LES JAMES TALKING with TERRY FROST JONES (Part 1)

Descendant of John Frost, the Chartist?

We met in 2007 at the ‘Stute’ on Stow Hill. It was the occasion of the first Newport Chartist Convention and ever since the first Saturday in November that year, I’ve been checking Terry’s progress with his family history research.

Terry was over from New Zealand, visiting family and had spotted the appeal Pat Drewett and myself had made in the Argus newspaper for descendants of Chartists to get in touch. Terry declared he was a direct descendant of John Frost.

I must admit, I had doubts. Frost is not an uncommon name and Terry was definitely not linked with any of John and Mary Frost’s seven surviving children, born between 1813 and 1826. Nor did his family have any apparent links with Newport, which rather undermined the idea that his ancestors were part of the wider Frost clan living in the borough.

Whenever I express my doubts to Terry, and I have from time to time, he reminds me of what he told the audience in 2007 - “Polly Harris, history teacher in Monmouth Secondary School, ordered me - ‘Frost Jones - stand up, boy!’’- and then she told the class “You are part of the living history of Monmouthshire.”

On Sunday, 4th November 2007, we boarded the Chartist tour bus organised for the second day of that Convention weekend and headed into the ‘Black Domain’ – the Monmouthshire coalfield. A regional name, adopted in tribute to the highly prized band of black bituminous coal across the middle of the coalfield, demonised in London’s governing circles. By the end of the 1830s, officials, sent by Government to inspect and report, were using the name ‘Black Domain’ pejoratively to define a region deemed ungovernable.

Our guide on the coach instructed us to exclude dual carriageways, motor vehicles and continuous urban conurbation from our vision and to erase from memory, the winding gear, railways, coal tips and terraced housing seen in post 1870s ‘Klondyke‘ photos.

Terry and I were back in 1839. We pictured the coal and iron workers swarming down to join forces with Newport’s Chartists. In the night of November 3rd -4th 1839, they followed ancient tracks and roads across the commons, atop the formidable mountains. Coming from the iron townships at the northern rim of the coalfield, they descended through hillside farmsteads to reach the tram roads. Along these, they passed through tracts of woodland near the valley bottoms, ‘scouring’ the scattered rural population, ransacking barns for implements to use as weapons, intimidating farmers to hand over firearms and forcing men into their ranks. And in the midst of the ‘coalfield’, the small ‘sale coal’ mining communities between Pontypool and Blackwood erupted. The men marched to the port of Newport that shipped out the product of their labour – coal and iron. John Frost led the men from Blackwood.

Talking with Terry, it was noticeable he had not just read the books; when he talks about John Frost, he lives and breathes the man, fitting him into his own time and place. We pictured the lives of men and boys working the levels (also called adits) that were driven into the valley sides, with linking tunnels, air shafts and shallow pits. And we recalled the rarely remembered young women who washed and sorted the coal in all winds and weather in the pock marked landscape, strewn with unmarketable waste. These are the people Frost addressed at the rallies held at Pontypool, Blackwood , Dukestown… and he won them to the cause of the People’s Charter.

Continuing, we passed through the continuous ribbon development of later years, then wild and rural in 1839, until we reached the edge of the high ground of the blaenau, the back end of the north to south flowing Ebbw Fach valley. We stopped at Salem Baptist Chapel, a Chartist exhibition centre, run in 2007 entirely by volunteers. Sadly, it’s now closed, due to dry rot. We had arrived at the northern edge of the coalfield, where in the 1830s, the three iron works of Blaina, Coalbrookvale and Nantyglo dominated the upper reaches of the Ebbw Fach and determined all in their surroundings. In the previous four decades, a new world had emerged. The total population of the rural parish of Aberystruth in 1801 was 805. By the late 1830s, nearly seven thousand Welsh, English and Irish speakers crowded around these works. Plentiful supplies of iron ore, limestone and coal in the vicinity meant similar iron making townships sprang up across the blaenau between Merthyr and Blaenafon. In those early years, coal was won at the surface by open cast ‘patching’ and iron ore was extracted by ‘scouring’. Along with Merthyr (in Glamorganshire) and the port of Newport, the coalfield parishes of Monmouthshire comprised the fastest growing population in mainland Britain.

We picnicked in and around the ruins of Ty Mawr, the ‘Big House’ which Joseph Bailey had brazenly built above the Nantyglo works in 1811. His brother, Crawshay Bailey lived there in 1839. Further up the mountainside, loomed two defensible Martello type towers, with iron doors and musket loops. Terry expressed a sense of oppression, something I too experience whenever I visit this site. Fearing a worker’s rebellion, Joseph Bailey had added barracks for troops in 1816. This site in Gwent brought back Terry’s memories of the terror regime that visitors encounter when visiting Port Arthur in Tasmania. Drawing on his reading of Frost’s description of life at that penal settlement (now a heritage site), Terry expressed his horror at the treatment meted out to his ancestor, John Frost and fellow prisoners. He views Van Diemen’s Land as a Gulag. And is proud of his ancestor’s patience as a prisoner, his brave endurance and return to Britain in 1856, when he challenged his oppressors.

We picnicked in and around the ruins of Ty Mawr, the ‘Big House’ which Joseph Bailey had brazenly built above the Nantyglo works in 1811. His brother, Crawshay Bailey lived there in 1839. Further up the mountainside, loomed two defensible Martello type towers, with iron doors and musket loops. Terry expressed a sense of oppression, something I too experience whenever I visit this site. Fearing a worker’s rebellion, Joseph Bailey had added barracks for troops in 1816. This site in Gwent brought back Terry’s memories of the terror regime that visitors encounter when visiting Port Arthur in Tasmania. Drawing on his reading of Frost’s description of life at that penal settlement (now a heritage site), Terry expressed his horror at the treatment meted out to his ancestor, John Frost and fellow prisoners. He views Van Diemen’s Land as a Gulag. And is proud of his ancestor’s patience as a prisoner, his brave endurance and return to Britain in 1856, when he challenged his oppressors.

Terry’s self belief derives from his earliest memories of childhood. “From my first day in school, I was very aware of my odd name, and whether or not it should or should not have a hyphen. Both my sisters didn’t add a hyphen to their surname and neither did Mum and Dad, when they signed something, so I never gave it much thought, just two surnames – that was OK by me.” It was Granny Lucy’s name too, but she had nothing to say about it. She was the widow of his grandfather, Edward. At the age of ten, Terry learned the importance of the name. He realised ‘Frost Jones’ went back generations.

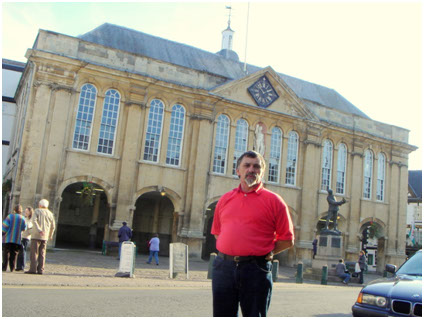

Terry with Local News reporter Jane Helmich in 2007

After Lunch, we sped on to Shire Hall, Monmouth, where John Frost faced a show trial that lasted eight days and concluded on the 16th January 1840 when he was sentenced to death, along with Zephaniah Williams and William Jones.

“It was on a coach trip to Blenheim Palace”, Terry remembers that “Aunt Marie, the wife of Sam, my father’s brother, enlightened me to the origins of the Frost Jones name. She was saying ‘Don't you take any notice of what other people tell you, I know for definite you, Bob and your cousins, my Robin, & Dot’s Raymond, are John Frost’s heirs. She never mentioned how it was so.”

All day, I kept probing. Terry, and his partner, Gaye, had quizzed family members on previous UK visits, but Terry’s knowledge of his family’s history went back no further than his great grandmother Eliza Frost Jones. His great grandfather Samuel was a mystery. Terry was told he had died before the First World War, but could find no date.

Eliza, and their son Edward, ran the family shoe repair shop in Monmouth at 17, Monnow Street, where Terry was born in 1944 and lived for the first nine years of his life. He knew neither Edward (d. 1922 aged 45) nor Eliza (d. 1935 aged 80). Terry was convinced that they both knew about the Frost connection.

Unfortunately, no family bible has been handed down. He thought it quite likely that Grannie Lucy, Edward’s widow, and very much in charge of the business, had more than an inkling. However right up to her death in 1966, she said very little to her sons, Sam and George, and silenced anybody like Aunt Marie, who dared to step out of line.

Late afternoon, it was an exceptionally balmy Autumn day, when our coach tour reached the quayside at Chepstow. In the early hours of Sunday (February 2nd 1840) Frost, Williams and Jones were brought here from Monmouth gaol.

As we stood on the side of the Wye, Terry mentioned he had read in Alexander Cordell’s Requiem for a Patriot about the miserable condition and treatment experienced by Frost; arriving manacled together, the prisoners stood hungry awaiting the steamer ‘Usk’ sent from Avonmouth to take them to Portsmouth for transportation. This must have been a poignant moment for Frost; he was leaving Gwent - and not as in previous times for business in Bristol or London. Sometimes a novelist captures the essence of a past situation, rather better than a historian, who is necessarily too focused on ‘factuality’. Cordell, writing in the voice of Frost, drew upon the generality of complaints Frost himself made of the British authorities, after his pardon and return from Tasmania in 1856, and directed them effectively into one dramatic event. The tarpaulin incident definitely occurred, but on another occasion. The weather conditions depicted - was it frosty or raining? The actual times of the prisoners’ arrival and the docking of the vessel, the numbers of police and prisoners, can all be questioned and argued about, but not Frost’s ‘personal’ experience as expressed by Cordell:

“pushed and squeezed into a waiting prison van, where five brawny constables sat, their batons drawn, ready to quell the smallest defiance. And the van, pulled by two stout horses, rumbled off along the Monmouth cobbles; a troop of Lancers with a pennant flying at their head, clattered their fine stallions alongside…… So we sat in the silence of men alive, but dead; bumping and swaying in the darkness of the van; listening to the clip-clopping of the horses and the ring of the iron-shod wheels. And when the dawn came raging over the hills, I saw through the barred window of the door a sun-flash upon water, and this was the River Wye…… Out of the van now, still chained together, we tramped in a chinking orchestra along the grass of the riverbank, with the towers of Chepstow castle lowering behind us…. The rain lashed us; it bucketed, it fell in slanting stair rods of pain that stung our faces…I had not eaten for two days, being unable to stomach the swill of the gaolers, and the unending diarrhoea…….‘Fetch a tarpaulin sheet and cover Mr. Frost before he dies on us’ ” (pp17-19).

Our coach returned to Newport, in time for the twilight gathering in the churchyard of St.Woolos (originally the parish church, now Newport Cathedral). We joined a large crowd, already assembled, all there to remember the twenty or more Chartists, who died on November 4th 1839, in the battle at the Westgate inn. Welcomed by the Dean of the Cathedral, the Mayor introduced proceedings, explaining briefly why we were there and other community representatives offered remarks, some poems were read and some sang ‘The Red Flag’. Sadly nobody attempted ‘Hen Wlad fy nhadau’. Flowers, mainly roses, were placed on the Chartist Commemoration Stone, unveiled by Alexander Cordell in 1988.

What stood out, starkly for Terry, was how time and circumstances change our perception of the past. The soldiers of the 45th Regiment were barely mentioned in passing at the ceremony. It’s a fact that no constables or soldiers perished, but several, along with more than fifty Chartists, suffered serious wounds. At the time they were lauded with dinners, prizes and honours. Thomas Phillips, mayor, seriously wounded, had been the hero of the hour and was knighted by Queen Victoria. Today, he went unsung. Whilst those considered heroes today were back then under threat of being hanged and quartered.

We discussed the reality. The battle lasted twenty minutes and left a scene of carnage. Wet, tired insurgents, who sought battle with the hated special constables, found themselves surprised and out-gunned by thirty trained, disciplined and rested infantrymen hidden inside the inn.

Fear of a counter attack caused Lieutenant Basil Gray to keep his men at their stations inside the inn for nearly two hours. The soldiers were under orders to stay put. They were not to pursue. He was conscious of the need to show he had acted only in self defence. Gray must have worried that his troops had indulged in overkill. George Shell endured a lingering death on the steps of the inn, medical attention or succour denied, but there was little attempt to prevent removal of the injured, the dying or the dead, who had fallen further away. Later that morning, the 45th lay out in the stables of the Westgate inn, nine bodies retrieved from the front doorway and inside the building and another found lying in Friar’s Field.

Fearing the wrath of sympathisers and supporters, soldiers from the very regiment that had fired upon the crowd, secretly buried these ten bodies. The exact position of the three unmarked graves is unknown, but townspeople, well aware of the site on the north side of the church, arrived on Flowering Sunday, 1840 and laid flowers. A tribute revived in the 1980s and carried out on November 4th every year since 1986.

Following Aunt Marie’s ‘family history lecture’, Terry had questioned his father and he reports he was led to believe the reason he had two names, Frost and Jones, “was because John Frost was the only survivor of the three prisoners sent to Tasmania. Mr Williams was married and had children, so ‘Jones’ was added to our name as John Frost thought it unfair that Mr Jones had perished in Van Diemen’s Land with no offspring to carry on his name. And he thought by combining both names Frost and Jones, then Jones’ memory would live on.” Where this concoction came from Terry does not know, but he thinks – ”probably my gran.”

My response to Terry was “Yes it’s a concoction butt it’s fascinating and important children’s ‘fairy’ tale. It reveals a family holding tenaciously to two precious pieces of knowledge gained from previous generations – They are saying - First, ‘our’ origins stem from John Frost and Second, ‘our’ name should be Frost. The name Jones is the appendage, not Frost.”

Terry went home in 2007 to New Zealand with a renewed determination to establish his credentials. He recognised his claim rested solely on one enduring fact - ‘Frost Jones’ had survived as his family name for generations. He was aware of four generations, back to the time of his great grandparents, Samuel and Eliza. The puzzle to solve was when and how the name originated. Did it have any connection with John Frost. Crucially, who was Samuel’s father? We kept in contact by email.

Terry returned in 2015, armed with a family tree, constructed by his Australian friend, and genealogist, Jean Bench. Taking advantage of the worldwide digital revolution, she checked online BMDs (Births, Marriages and Deaths) and Census returns and found Edward Frost Jones, shoemaker, was the father of Samuel Oscroft Frost Jones.

Gwent Archives had placed its 'Chartist Sources' handbook on-line with details of the microfilm copies that they have of the birth and baptism register (ref.RG4) for Hope Chapel, Newport held at the National Archives. The births of John, Elizabeth, Sarah, Catherine, Ellen, Henry Hunt, James and Ann - the children of John and Mary Frost, 1813-1826 - were recorded. Also an entry made in 1836 for the birth on 7 December 1827 of Edward, son of Mary Jones, identified as ‘not born in Wedlock affiliated to Frost’.

*********

Part 2 of Talking with Terry Frost Jones continues in the next edition (CHARTISM e-MAG, no.16)

Les James looks closely at Terry’s family tree and with the help of Sarah Richards, expert on the Frost family, finds out more about Mary Jones and her son Edward

He talks with Terry about growing up in Monmouth and the mystery of his great grandfather

And asks - Can we really establish which member of the Frost family was Edward’s father?