Descendants of John Frost

By Sarah Richards

Within the Chartist movement there was a tradition of naming children after prominent individuals, which must cause some confusion now that ‘doing your family history’ has become a widespread activity. I wonder how many people have spent time looking for an Irish element in their family having come across an ancestor named Feargus O’Connor, when such a name more than likely indicates an association with Chartism. Some people have both a significant name in their family and handed-down awareness of a connection, though as for Terry Frost Jones, this also presents challenges (Les James ‘Talking with Terry Frost Jones’ (part1) Chartism e-Mag 15 Autumn 2018).

I was lucky enough to have one of my family, William Davies of Blackwood, give me the crucial clue himself that he was a Chartist in a letter handed down in my family. That started me on a journey looking into his involvement in the Rising, his life afterwards, and through his marriage to Ellen, one of John Frost’s daughters, finding out about the Frost family and their descendants. It has led to me wondering in what ways those who experienced such major events found it influenced their later lives. There is always the hope in situations like this that descendants will come forward, bringing an awareness of their own family’s involvement.

The Frost family

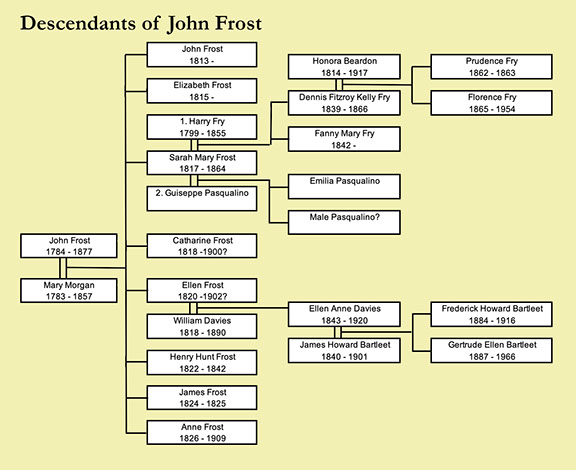

John Frost, draper of Newport, married Mary Geach, nee Morgan, the widow of a wealthy timber merchant, at Bettws Church near Newport on 24 October 1812. She already had two children by her first marriage, William Foster Geach born in 1804 and Mary Foster Geach born in 1806. Over the following fourteen years, John and Mary Frost had eight children, registering them at Hope Chapel, Newport:

John born 8 October 1813

Elizabeth born 18 March 1815

Sarah born 16 January 1817

Catharine born 16 October 1818

Ellen born 17 September 1820

Henry Hunt born 1 August 1822

James born 7 August 1824

Anne born 1 July 1826

Of the children, James died at the age of only 5 months. John, the eldest, has long been said to have disappeared to America. There is a record of a John Frost aged 22 arriving in New York on 4 January 1836, which tallies with his birth date. It seems he may have emigrated because of family issues. Critics of his father claimed the son disagreed with his father’s politics. Unfortunately no further records have yet been found for him either in America or back in Britain. There is nothing to suggest that he met his father during his eighteen months in New York in the mid-1850s.

Henry Hunt Frost was active in the Chartist movement, living up to his name, that of the great radical orator who spoke at St Peters Field, Manchester, ‘Peterloo’, in 1819. Aged only 17, Henry Hunt Frost operated as a courier for the Chartist movement and after the Rising was brought before the examining magistrates on 14 November 1839. He was discharged because no arrest warrant had been issued. By the time a warrant was eventually issued he had absconded and remained on the run for many months, apparently not pursued by the authorities.

He is visible again in early January 1841, speaking at a meeting in Merthyr, and soon afterwards in Bristol, reading out Frost’s letter from Port Arthur. Then he is out of the news again until his death on 22 March 1842 of a lingering illness or ‘decline’. His death was widely reported, as were the funeral sermons preached for him throughout the country, accompanied by collections for the transported Chartist ‘martyrs’ and their families.

After the Rising

In the aftermath of the Rising, soon after John Frost’s conviction and transportation, his stepson William Foster Geach was convicted on a charge of fraud and also transported (7 years). His removal to Van Diemen’s Land was closely followed by Henry Hunt Frost’s illness and death, and so in the absence of close male relatives it was the women who held the family together and fuelled the campaign for John Frost’s pardon. They come across as resourceful, sometimes adventurous, and active beyond the domestic sphere. Though their politics is seldom explicit, their support for Chartist values and their family loyalty can be clearly seen.

At the time of the Rising, John Frost’s wife Mary was in her fifties. She is said to have shared his politics and to have been a leading figure in the Female Association of Chartists at Newport. At home with her were four daughters, Elizabeth, Catharine, Ellen and Anne, none older than their mid-twenties. Frost’s step-daughter Mary had married Pontypool tanner George Lawrence in 1830 and died in the autumn of 1840. Soon afterwards the Frost family moved to Bristol:

‘Mrs Frost and her family are now residing at Montpelier… in a respectable house, and apparently in easy circumstances. Her son, who was influenced by his misguided father at the Newport riots, has been placed with a chemist, in Bristol, and the second of four daughters, now residing with Mrs Frost, is about to proceed to France, for the purpose of completing her education, to qualify her for the situation of Governess.’ (Bristol Times and Mirror 14 Nov 1840)

The fifth Frost daughter, Sarah, had married Newport surgeon Harry Fry six months before the Rising. Apparently John Frost did not attend the wedding; certainly he and his son in law were politically opposed, as demonstrated in April 1839 when Harry Fry addressed a meeting in Newport of landed proprietors called to oppose Chartism. Despite this, when Sarah and Harry Fry’s son was born in December 1839 he was named Dennis Fitzroy Kelly, taking the name of one of Frost’s barristers as his middle names. Their daughter Fanny Mary was born in August 1842.

Later in the 1840s Mary Frost moved to Stapleton near Bristol with her daughters Catharine and Anne, and from the time of the 1851 census at least, also her grand-daughter Fanny. Ellen Frost had by then married William Davies, (the young Chartist I discovered in my family letters). Son of Roger Davies, a Blackwood grocer, who was a close friend of John Frost, he ran away after the Rising, and was arrested at the home of his uncle, a minister in Canterbury. Mr. Evans, special constable from Newport was in pursuit and the local police took him into custody. He returned to Newport for questioning and cooperated with the authorities, providing details of Chartist activities in the days preceding the Rising. He absconded again before the trials, staying away for nearly a year, and was never captured. He and Ellen Frost married in 1842 and their daughter Ellen Anne was born in 1843. At the time of the 1851 census, they were back living in Blackwood with a drapery business and with Elizabeth Frost shown as housekeeper.

Changes in the family

In the 1851 census Sarah Fry appears in Newark on Trent, Nottinghamshire, in the house of John Logan and his family. He was an engineer, a political reformer and a close acquaintance of her father, whose wife Elizabeth was a sister of William Anselm Townsend, the Newport Chartist. A report in the Bristol Mercury (26 November 1853) revealed that Sarah’s marriage had broken down some years before. A Bristol silk-mercer and draper took her husband Harry Fry to court to recover the cost of goods supplied to Sarah. She claimed it was Fry’s money troubles which caused her to leave him, not differences arising from her conversion to Roman Catholicism. Fry disagreed, saying his financial difficulties were caused by the impact on his surgeon’s business of the Frost connection. With opposing politics, Fry is unlikely to have wanted to associate himself with the campaign to release Frost. Eighteen years older than Sarah, he died in 1855.

While giving evidence in court, Fry mentioned that Sarah had a sister, ‘a married woman [who] also lived apart from her husband, who had gone to Australia.’ This was Ellen: earlier that year her husband, William Davies, and Catharine Frost had travelled to Australia. For William it seems this may have been an exploratory trip, in anticipation of moving to Australia. Catharine was joining her father, the family having been tipped off that Frost, now 70 years of age, might at last be pardoned.

In 1854, probably in March, Catharine joined Frost in Van Diemen’s Land, his conditional pardon was granted soon afterwards, and in December they left for the United States, travelling via Callao in South America. A full pardon was granted in 1856, whereupon they returned to Britain and to Stapleton. As the dust settled following Frost’s celebratory appearances and lectures on his return, there were more changes in the family. Mary Frost died in 1857. In the following year Sarah Fry made a remarkable second marriage, to the Marquis Giuseppe Pasqualino, in Palermo, Sicily. She died in 1864, according to some sources leaving a daughter, Emilia, and possibly also a son.

William Davies returned to Britain but did not stay here. In late 1858 he returned to Australia with Ellen and their daughter Ellen Anne, and it seems that Catharine Frost went with them too. The family household in Stapleton settled into its final form in the 1860s and 1870s, when John Frost lived with his daughter Anne and grand-daughter Fanny Fry. Elizabeth Frost was there too for the 1861 Census, but cannot be found afterwards. She is assumed to have died by 1874 because she is not mentioned in Frost’s will which was made then.

After Frost’s death in 1877, Ellen chose family over husband and returned to Britain with her daughter, leaving William behind in Australia. Catharine’s return is also confirmed by newspaper reports in February 1884. An action for libel was brought by Mr Robert Graham against Miss Frost of Weymouth. Graham was the solicitor who drafted Frost’s will. While disputing some accounts, Catharine wrote to his partner accusing Graham of defrauding her. The case was not defended: it was agreed that, whether or not she accepted the accounts, Miss Frost ought not to have made the charge of fraud, and nominal damages of £10 were awarded. Is there perhaps a hint of Catharine’s character in this, a hasty letter followed by a retraction on the advice of her solicitor?

Radipole and final glimpses

By 1881 a new Frost household had been established. Anne was now in Radipole, a developing suburb of Weymouth, Dorset, with her niece Ellen Anne Davis and two Lawrence children, Ethel aged 7 and Willie aged 6, described as great niece and great nephew. The parentage of these children is as yet a mystery, though they presumably came from somewhere in the Lawrence family connected to the Frosts by marriage. Ellen was in Stapleton, in the household of James Street, a customs officer who witnessed John Frost’s will.

In 1884 Ann Frost, describing herself as ‘daughter of John Frost, patriot and martyr’, published ‘A Plea for Innocent People Convicted and Imprisoned’. The review in Reynolds’ Newspaper gave her defence of her father’s involvement in the Rising, quoting her as saying that ‘rebellion was never organised by him; he was the victim of a conspiracy formed to entrap him.’ She said, having failed to calm the situation, ‘he stood by men he taught to think, to consider rights, but never by him trained to fight’. In publishing this she was fulfilling a final commitment to Frost.

In the 1891 Census, only Ellen can be found with certainty, at Radipole with Ethel and William Lawrence. Ten years later she was with the Bartleet family in Portsmouth, her daughter Ellen Anne having married James Howard Bartleet. He died in Croydon in 1901 and a possible death has been found for Ellen there in March 1902. For Catharine there is one more newspaper report, an advertisement by Weymouth solicitors in 1900 calling for anyone having a claim on her estate to send particulars, following her recent death at Kingston on Thames. There are possible death and burial records, though the first name is given as Caroline.

For Anne there are possible later Census records in London, in 1891 with Bartleet relatives, and in 1901 in a home for the elderly poor. It seems she may have been elusive even at the time, if she was the Miss Anne Frost regarding whose whereabouts a firm of Weymouth auctioneers advertised in October 1891. She died on 16 May 1909 in Kensington, Middlesex.

The women of the Frost family

In the picture which is building up of the Frost family, the roles of Anne and Catharine seem quite contrasting. For many years Anne took on the steadfast, dedicated work of maintaining a family household, providing stability on tight resources. When her father died she kept out of public view, asking a family friend to pass on the news, and it was only some years afterwards that she came out into the open and published. In this she seems similar to her mother: in earlier years Mary Frost also focused on keeping the household and the family’s finances going, speaking out publicly only when she felt she had to.

Catharine took a bolder and more adventurous path; hers was a life much more lived in public. She took a leading role in the campaign for her father’s freedom, for which she travelled round the world, she went back to Australia a second time and returned, still ready to fight her corner when she thought a solicitor had wronged her. There is as yet little evidence regarding Sarah and Ellen from which to form a general view of this kind, and very little information of any kind about Elizabeth.

The final fading into oblivion of the Frost daughters seems sad. It is almost as though, having experienced the spotlight of public attention early in their lives, they chose obscurity towards the end. It is quite possible, though, that more is still to be found out about the Frost family, in sources not yet considered or in newspapers not yet available for digital searching. Perhaps drawing attention to them in this way will encourage further investigation of their lives, and their place in Chartism.

Sarah Richards 2019