Democracy, Privilege and Inequality

Riches and Rebellion at Tredegar House.

Goff Morgan, Volunteer Day Coordinator, National Trust

How the Nation’s Leading Conservation Charity “dipped its toes into the stormy waters of radical politics” with its Riches and Rebellion Exhibition” (September 2019 – March 2020)

According to its constitution, the National Trust has an obligation to remain apolitical. Although more than happy to be known as an organisation that invites questions and opinions from visitors to the many places in its care, it has not got a reputation for dipping its toe into the stormy waters of radical politics.

However, when Tredegar House came under the management of the National Trust, there was an inevitability that politics would rear its head at some point.

The Morgans were deeply embedded in the political system, both locally and nationally, for centuries. Twenty-two men of the family were Members of Parliament, and at the height of their political influence four seats were in their gift. The Morgan Influence, as it was referred to, was a significant political entity in south east Wales.

During the early nineteenth century, the family was at its most active and obvious. They rose from the ranks of wealthy agricultural landowners to become major industrialists, property developers, and infrastructure investors on a truly colossal scale. They were part of an essentially oligarchical grouping that had changed little in practical structure from the feudal system. The landowners sat in the House of Lords, their sons and minor gentry filled the seats of the House of Commons. They also filled the seats of the local magistrates, commissioners, clergy, alderman and royal representatives from sheriffs to lord lieutenants. The Morgans, and families like them, were “the establishment”, and the system ran for their benefit.

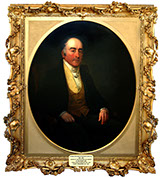

It is clear with hindsight that this family would become in south east Wales, the principal focus of animosity from the Chartist cause. They represented everything to which Chartism was opposed, and Sir Charles Morgan (and primarily, his land Agent, Thomas Prothero; left) were seen as the main opponents by the Chartist leader, John Frost.

It is clear with hindsight that this family would become in south east Wales, the principal focus of animosity from the Chartist cause. They represented everything to which Chartism was opposed, and Sir Charles Morgan (and primarily, his land Agent, Thomas Prothero; left) were seen as the main opponents by the Chartist leader, John Frost.

Over a lengthy period of time, five of the six demands of the People’s Charter have been implemented (however grudgingly), and it may be said Chartism ultimately triumphed. However well known this period of turmoil, uprising and tragedy is to the people of Newport and south east Wales, its national relevance is still a developing story. It is only within the last two decades that the tragic deaths by military gunfire of twenty two chartists, and the routing of many thousands more from the failed uprising in Newport of November 4, 1839, was referred to as anything other than a riot – a little local difficulty.

In a typical year, the National Trust receives nearly 95,000 visitors annually to Tredegar House, the majority of whom will know little, if anything, about the story. To tell this complex history in an introductory, informative, and engaging way, the “Riches and Rebellion Exhibition” (September 2019 – March 2020) had a difficult job to do. It needed to tell the history of how the Morgans were caught up in the political upheavals of the period, and the reasons for their opposition to the democratic structures that we, perhaps, take too much for granted today, without becoming apologists for the family and the system they were seen to represent. This balance was achieved, I believe, by positing questions and contrasts throughout the exhibition, and allowing the visitors to engage with the topics and think about the contrasts presented.

It would not be practical to take readers on a “guided tour” of an exhibition that has concluded, but it may be helpful to give three examples to illustrate some of the themes that were addressed within it.

When visitors arrived at Visitor Reception they were presented with a ballot slip asking the question, “Are you entitled to vote?”. They placed their cross in the appropriate “Yes” or “No” box and headed through the Orchard and Cedar Garden to the House. As they walked along the gravel path, beside the Cedar of Lebanon, they saw the six points of the Charter displayed on protest placards either side of the walkway. On entering the House, they were directed to the Ballot Box for the Constituency of Monmouthshire and asked if they could afford a rent of £42,000 annually. If yes, they placed their vote in the ballot box; if no, their vote was discarded, in the waste basket beside. Over the six months of the exhibition, the cast votes barely filled the ballot box, and the discarded ballots piled up.

Once in the House, they proceeded to the Gilt Room – a room dripping with gold leaf, marble and expensive painted panels and deceits – and saw on the drawn blinds of the room copies of contemporary engravings depicting scenes of early 19thC life and industry that the Morgans owned, and from which they profited extensively.

Then in the Brown Room – the State Dining Room – a room with extravagant 17thC carved oak in the style of Grinling Gibbons, and an original hand cut 17thC oak floor – they were surrounded by the piled up bottles of wine that Sir Charles Morgan consumed annually. In the centre of the room was a small carpeted area, a mere eight feet by eight feet, furnished in the manner of one of the worker cottages lived in by the employees of Morgan industries. A nearby information panel informed the reader that this represented the average living space of a working man and his family.

The portrait of John Frost, Chartist leader and arch-critic of the Morgans, gazed down from the over-mantle of the Gilt Room, accompanied by the stirring singing of Chartist marching songs; it was an engaging flight of whimsy to wonder what he would have made of it all. It was up to the visitor, to reach their own conclusions.

The portrait of John Frost, Chartist leader and arch-critic of the Morgans, gazed down from the over-mantle of the Gilt Room, accompanied by the stirring singing of Chartist marching songs; it was an engaging flight of whimsy to wonder what he would have made of it all. It was up to the visitor, to reach their own conclusions.

The National Trust devised the Riches and Rebellion exhibition to enable visitors to engage with issues of democracy, privilege, and inequality via the history of the Morgans and Chartism, issues that are as current today as they were in 1839. It is arguable that the Trust's ownership of the estates and homes of the former ruling class, and its policies of accessibility and community engagement, have to a greater extent democratised the Stately Home. The Trust's motto - “Forever, For Everyone” - is a sentiment of which I feel Frost would have approved.

Did you see Riches and Rebellion exhibition? CHARTISM eMAG would like to hear from you

Contact Editor: les.james22@gmail.com