A House Through Time

10, Guinea Street, Bristol

Andrew Willie

The most recent of David Olusoga’s House Investigations, broadcast on BBC2 during the summer of 2020, tells a well nuanced and quite complex set of tales.

A timely revelation of the past occupants of an early Regency House built near Bristol’s quayside in the time of the Slave Trade. This ‘house through time’, prepared months before ‘Lock Down’, appeared on our screens in the wake of Colson’s dunking in the Bristol dock.

A quote from David Olusoga

“I felt a certain kind of sadness that we were showing the city, the harbour and the cider, and people couldn't do that anymore"

10, Guinea Street, Bristol was built in 1715; its location was close to the recently extended Bristol Docks. The street was named after the coastal area of west Africa, where Bristol traded.

The formula of the programme series is a simple one: to explore social history through the owners and tenants of a house. And this is the third such series for which David Olusoga has been responsible; the first concerned a house in Liverpool, the second one in Newcastle. Although the Newcastle study earned the house a blue plaque from the discovery that Joshua John Alder, distinguished Victorian naturalist, once lived there, the present series has proved to be the most interesting of all. Probably because it concerned a house of much earlier build than his previous two case studies.

Olusoga’s sources are wide ranging. As to be expected, Bristol Archive Office, the National Archives at Kew and the British Library were where they were found - Property deeds, electoral rolls, census returns, a slave database, local newspapers, a contemporary print of a Hogarth cartoon, letters, diaries and pamphlets. The array was fascinating and although Olusoga did it all justice, the first hundred or so years provides by far the most interesting part of the story he tells.

The first two occupants were both ship captains involved in the slave trade. Captain Edmund Saunders succeeded by Captain Joseph Smith. They were both involved in the triangular run: pots, guns and trinkets were shipped from Bristol to West Africa and exchanged for slaves: the slaves were transported, ill-fed, in cramped, unhygienic conditions across the Atlantic, many perishing on the way, to the West Indies; once there, they worked on sugar plantations, having been exchanged and sold for sugar-cane, which was brought to Bristol for the delectation of the British palate.

Saunders is recorded as having made 200 slave journeys and Smith as encountering in Bristol, a pirate captain who formerly had seized his ship. Saunders’ obsessive attempts to bring the offender to book seemed to have worked eventually, but after the death sentence had been given, a pardon was granted. As usual, Olusoga had researched the matter as thoroughly as he could but failed to find the reason either for the diffidence of the authorities in proceeding in the first place or for the pardon. Olusoga is not the sort of presenter to gloss over gaps in his knowledge. Unanswered questions are as important to him as those for which he has a ready answer.

The next occupier was Joseph Holbrook, a sugar trader whose family had a negro lad, Thomas, as a domestic slave. He would have been very much a status symbol for a wealthy middle-class family. His English was good. We know this from an advertisement in a local paper which announced he was a runaway, and the Holbrooks wanted their property returned. It seems possible that Thomas was recruited by the Royal navy, and that would have meant he received a wage and, if he survived, a retirement pension.

After stories of slavery, politics becomes Olusoga’s central theme. This phase of occupation began with Dr John Shebbeare, an anti-Hanoverian monarchy, Tory pamphleteer, who is listed in 1750 land tax records as being at 10, Guinea Street.

He was guest at a dinner party at which the first female novelist, Fanny Burney, was present. In her diary she recalls how his misogynistic rudeness masqueraded as wit. On the 28 November 1758, his pamphlets, found in the British Library, landed him three years in prison, a day in the stocks, where his hatred of the Hanoverians meant the crowd handled him gently and a place in one of Hogarth’s electoral cartoons, an engraving called The Polling.

He was guest at a dinner party at which the first female novelist, Fanny Burney, was present. In her diary she recalls how his misogynistic rudeness masqueraded as wit. On the 28 November 1758, his pamphlets, found in the British Library, landed him three years in prison, a day in the stocks, where his hatred of the Hanoverians meant the crowd handled him gently and a place in one of Hogarth’s electoral cartoons, an engraving called The Polling.

He died in 1788 in Pimlico, having fallen into debt, and lost his connection with Bristol.

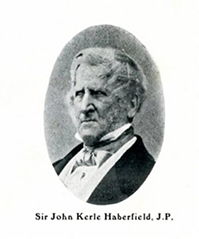

Radicalism and Chartism appear on the scene with the story of John Haberfield, who moved to the house with his parents in about 1803 and the following year, at 19, he became an articled solicitor’s clerk. He then set up his own practice, married well and became six times Mayor of Bristol. Mayor in 1838, he was frightened at the prospect of gatherings in Bristol, especially in the light of the massive meeting held at Glasgow in support of the People’s Charter in May of that year. (He would have received news of John Frost’s presence and his reported support of physical force in his speech).

Haberfield remembered 1831, when rejection of the first Reform Bill by the House of Lords, led to rioting in Bristol between October 29th and 31st that year. Cavalry charges resulted in at least 250 casualties and £300,000 worth of damage, particularly the setting alight of the houses in Queen’s Square.

Haberfield remembered 1831, when rejection of the first Reform Bill by the House of Lords, led to rioting in Bristol between October 29th and 31st that year. Cavalry charges resulted in at least 250 casualties and £300,000 worth of damage, particularly the setting alight of the houses in Queen’s Square.

On that occasion, Charles Pinney, the Mayor stood trial for letting matters get out of hand. He was acquitted, but Lieutenant-Colonel Brereton, found guilty at Court Marshal of neglect, committed suicide, firing his pistol.

Olugosa told us of Haberfield’s nervous correspondence with Lord John Russell’s administration. He feared that Chartist gatherings encouraged in the city by Henry Vincent during 1838/9 could similarly get out of hand as happened in 1831 and Olugosa suggested that Haberfield’s resulting inaction, probably saved the day and brought him a knighthood eventually in 1851. As a result of his indecision, the West country Chartist riot that Haberfield expected, happened not in Bristol, but in Newport where Vincent turned his attention in January 1839.

During the remainder of the nineteenth century, the neighbourhood of 10, Guinea Street was changing and after Haberfield, the occupants of the house reflect a very different social world. We learn of Ann, the daughter of sea-captain John Holbrook, considered a disgrace to her family; and of her bigamous Baptist minister [temporary] husband, a pamphleteer who fled to Pembrokeshire; of William Martin who wished to teach accountancy at the house, but aged 27 developed schizophrenia and ended his life in a mental hospital; of a wish by a couple to serve the Temperance movement which resulted in their prosecution for watered-down milk and of a large family who made the house their home before the 1st world war and afterwards.

Though the three daughters were widowed by war [one remarrying] the last addition to the family, born in 1928, was able to tell Olosuga of how happy they all were in the house. He interviewed her with an empathy which was quite touching.

The Wallingtons were the next owners and they accepted tenants. Among them were Isaac and Mary Long, victims of the 50k German bomb which fell in 1940 on nearby number 5 Guinea Street, damaging it and surrounding houses irreparably, when 148 German bombers descended on the city. We learnt of Cyril Tabrett, a tenant whose only success as a conman was to confuse everyone, including briefly Olusoga, as to his identity and of a young Ethiopian refugee whom the current owners have supported.

Olusoga has been rebuked for the way in which the story seemed to tail off, but that is the result not of his scholarship and presentation but of our snobbery, leading to our finding the later poorer tenants and owners less interesting. When the series ended, the house with original fireplaces, at least one stuccoed ceiling and a ground floor cellar waiting to be turned into an office [as working from home becomes more common after lockdown] is now on the market for £800,000. This means only the most prosperous, as the first owners were, can afford once again to live there.

I had hoped that having mentioned Newport as a centre of west country Chartism, Olusaga might use a house in Newport for his next project: he has already turned his attention to Leeds. However, I can see this informative and entertaining series going on for years. If you have any ideas about any special house in Newport, which might merit investigation, would you please let the Editor know.

David Olusoga’s BBC2 programme series was first broadcast on BBC 2 at on Tuesday evenings between May 19th and June 9th, 2020.

Now available on I-Player

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m000jjn8/a-house-through-time-series-3-episode-1