THE VOYAGE OF THE USK February 1840

‘Steam Packet Bristol 1822’ – George Tobin

(National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

In early 1840 the country was in a feverish state of excitement following the sensational Chartist trials in Monmouth. The leaders of the Rising, John Frost, Zephaniah Williams, and William Jones had been convicted of treason and on 16th January were sentenced to death. Following this there was a delay so that legal objections raised by their defence Counsel could be heard in London at the end of January. In the meantime supporters of Frost, Williams and Jones up and down the country were deluging the Queen and Parliament with petitions calling for clemency, while their opponents were calling for examples to be made through the imposition of the severest possible punishments. In Monmouth, the prison governor was overseeing preparation of the gallows. The authorities needed to handle matters very carefully to avoid inflaming the situation further.

On 18th January 1840 Henry Mostyn, Under-Sheriff of Monmouthshire, wrote to the Home Secretary, the Marquess of Normanby. Believing swift action would be advisable following the decision on the legal objections, he warned that time would be required to find a competent executioner, especially if the full sentences were to be carried out, by beheading, drawing the bodies on hurdles and quartering them.

Clearly fearful of his responsibilities, he also drew attention to the change of High Sheriff, which usually took place about the 3rd or 4th of February, and asked for:

“ . . . such orders as may be thought proper to avoid any question or uncertainty that may possibly arise between the outgoing and incoming Sheriff, as to who is to go through this painful duty which each of us will be desirous of throwing on the other.”

Mostyn would have been aware that the High Sheriff for Monmouthshire for 1840 was intended to be Summers Harford, a Quaker ironmaster and magistrate, a reform supporter thought to have Chartist sympathies. Having apparently not yet received a response from the Home Secretary, he wrote again on 29th January saying that urgent business obliged him to go to London and he would call at Normanby’s office on Saturday that week to make enquires concerning orders and directions.

On that Saturday, 1st February, in Mostyn’s absence, Daniel Esbury Partridge, his clerk, acknowledged receipt of a letter from the Home Secretary

“ . . . wherein you signify the Queen’s commands that the execution of the sentence of death passed upon John Frost, Zephaniah Williams and William Jones now in the Gaol of Monmouth be respited until further signification of Her Majesty’s pleasure”

This news was already in circulation. The Monmouthshire Merlin reported the same day that a document, from the Home Office directed to the High Sheriff inscribed “A Respite”, had been seen passing through Monmouth post office the previous Thursday. This was initially assumed to mean that the death penalties would not be imposed, until Mostyn arrived in Monmouth that evening with an order simply deferring the executions for a further week.

In London, the decision to reprieve had in fact been taken on 31st January, and with leaks and rumours circulating the authorities were moving as swiftly and discretely as they could to remove the convicts for transportation. On Sunday 2nd February Superintendent John May, commander of the Metropolitan Police “A” Division, wrote from Bristol to the Commissioners of Police in London:

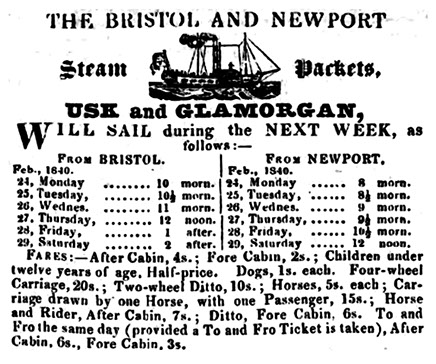

“Gentlemen, agreeable to the directions I received from the Secretary of State I immediately waited on Messrs Geo. Lunell & Co. the Steam Packet Company who have promptly provided me with a vessel called the Usk which is to leave here this afternoon and will reach Chepstow about 8 o’clock, and the instant I arrive there I shall proceed to Monmouth so as to be able to return with the Prisoners between 6 & 7 o’clock tomorrow morning if nothing extra occurs at Monmouth to prevent their removal.”

Superintendent May was well served by the Company. Both the captain and the ship, of a similar size and design to its forerunner (pictured above), were described in glowing terms in the Cambrian (02.06.1838) when the :

“NEW STEAMER USK.- We have much pleasure in announcing that a new and beautiful Steam Packet, named the Usk, built expressly for the Bristol and Newport station, made her first appearance at the latter port on Wednesday se’nnight, and will commence her regular trips in a few days. The Usk is pronounced by competent judges as admirably calculated for the peculiar navigation between the two ports and will considerably abridge the present average period of the passages. She is constructed with a round stern, is of exceptionally light draught, and in the accommodations for passengers, is perhaps not inferior to any packet of her size on the water. Her saloon, comfortable and commodious, is fitted up with elegance, and the furniture and decorations do much credit to the taste and spirit of the proprietors. Capt. Parfitt, whose uniform civility and vigilance, merit honourable mention, is to command the Usk.”

There may also have been politics behind the choice of Captain Parfitt for this task. Those relying on his services on the Bristol Channel steam packet routes found Parfitt’s conduct so exemplary that within nine months of the new service he was presented in March 1839 with a silver plate tea service and a testimonial, at a handsome supper attended by commercial and other gentlemen. There were 171 subscribers, and the Monmouthshire Beacon pointedly observed that “this tribute of respect was given by a union of all parties, except Chartists.” (30.05.1839)

Removing the convicts by sea was the most secure option, but if the authorities expected that immediate transfer under cover of darkness would ensure secrecy, they must have been greatly disappointed. By Tuesday 4th February, the newspaper reports of Frost, Williams, and Jones’s stay of execution, were superseded by news of their removal to the Usk, for the voyage to Portsmouth and transportation.

Wednesday 5th February, the Morning Post carried reports from a ‘Bristol Correspondent’ providing details of Superintendent May’s visit to the Steam Packet Office, his pressing of the Usk and the boarding of the prisoners, soldiers and police. The correspondent reported that after leaving Chepstow, the Usk had ‘put back to King Road’ at the mouth of the Avon and on Monday night was lying in Broad Pill, Bristol, taking on coals and provisions. The ship had been visited and it was noted that:

“One of the police is constantly in the cabin with the prisoners, and a sentinel keeps guard at the door. There are 14 of the 19th infantries, Lieutenant Langley, and a sergeant on board, and six of the A division of the London police, under the direction of sergeant Withingford (sic).”

Despite this security, remarks made by the prisoners were recorded and their behaviour on board described. With this level of press attention, it must have been a relief to the authorities that the Usk would be leaving Bristol early the following morning and was expected to take only two days to reach Portsmouth.

Also, on board the Usk with the prisoners was Charles Ford, Governor of Monmouth Gaol, who wrote to the Home Office from Ilfracombe on Tuesday 4th February to report progress:

“I beg to acquaint you for the information of the Secretary of State that we sailed this morning from off Bristol and arrived at this place at 4 o’clock this afternoon after laying on the tack for nearly two hours before the state of the tide would allow us to come into the harbour & then and had been blowing tremendously and still is so doing now and not likely to moderate in consequence of which the Captain of the vessel says that he cannot leave here until the weather alters for the better.”

A letter to the Home Office written a few days later by Sergeant of Police John Witheford, aboard the Usk, gave journal entries for this part of the voyage. He recounted worrying news received on 5th February while still at Ilfracombe:

“Wind the same, and the Gale still continued: at 7 P.M. Lieutenant Langley, commanding the Escort Received a note from Mr Lee, a Magistrate, stating that a Rumour, was about relative to Frost & others, being aboard; which was confirmed by that evenings Paper: Lieutt Langley, went to the Magistrates and at his request I accompanied him: Mr Lee said he had no apprehension as far as the Inhabitants of Ilfracombe, were concerned but in the event of our being Wind Bound, for some days, he felt rather concerned, in case the Inhabitants of Barnstable or Bideford, should contemplate any Rescue: he proffered to collect a small Body of the preventive service men; which the Lieutt respectfully declined, stating his hope, that we should get under way in a few hours & if not he would again see Mr Lee; on the subject.”

Ford wrote to the Home Office again from Ilfracombe the following day, 6th February, at last able to report that the Usk had sailed but anxious about the newspaper coverage:

“I beg to acquaint you that we have this moment set sail from hence to the Lundy Island where we shall anchor for the night hoping to be able to sail by tomorrow mornings Tide from thence but the wind his still against us but as it’s become more calm the Captain says he will strive to be able to get to Falmouth or Devonport tomorrow & proceed the next day to our final destination if possible.

P.S. We are very anxious to leave here in consequence of the London Papers having stated that we are aboard of this vessel or else no one knew who was aboard.”

From Witheford’s journal entry for the same day, Captain Parfitt’s concern about the weather was justified:

“Thursday 6th Wind the same, but a little abated: Started from Ilfracombe at 4 P.M. – got down to Lundy Island at 9 P.M. proceeded to Westward, but the sea running high: the Wind Increasing: the sea running higher: at 3 A.M. the vessel shipped a very heavy sea: knocked the man down at the Wheel: and carried the compass overboard; and also the loose things laying on Deck: broke two stanchions also carried away the Bulwark: got another compass fixed; and about 6 ½ A.M. made the Land: distant about 2 miles: from some Rocks, called the Rainer (?): about six miles from Padstow: ran for the Harbour: blowing then a Tremendous Gale: Wind N.W.

Padstow is one of the few sheltered harbours on the rocky north Cornwall coast but the prisoners had to be isolated, so the following day Witheford finished his letter to the Home Office by explaining that the Usk had moved to a creek on the Camel estuary:

“Saturday 8th Wind & Weather, still continues as yesterday: had a terrible rough night: we are laying in a creek: 2 Miles from the Harbour no other vessels, near us, nor any communication with the shore: I beg to state: 4 vessels were lost: near this harbor the night prior to our arrival.”

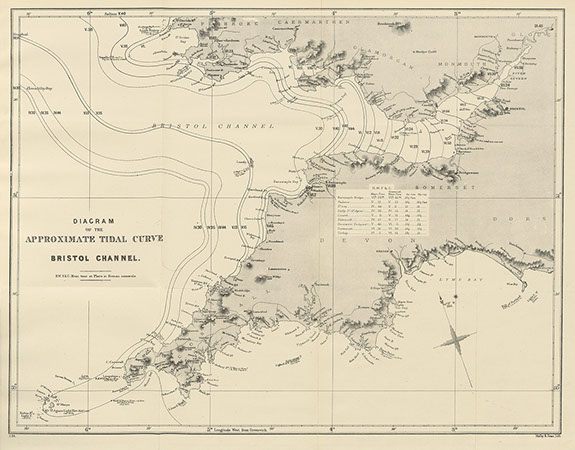

“Sailing Directions for the Bristol Channel” compiled by E J Bedford 1884 (British Library)

By Tuesday 11th February, the Usk had reached St Ives, but the weather remained poor. Ford wrote to Mr Capper, Superintendent of the Convict Establishments (Hulks), regarding arrangements if there was a lengthy further delay:

“I have made bold to write to you Informing you that we was obliged to put in here this day at 2 oclock the weather being so boisterous as not to enable us to go round the Landsend nor from all the information I can learn it may be a month or long before we shall be able to leave this, there is several vessels which have been 6 Weeks wind bound here and there was a revenue cutter tried to go round this day but could not and as its only 11 miles by land from hence to Falmouth the Officer commanding the escort and myself considers it adviseable to take the prisoners from hence to Falmouth by Land and get a fresh escort and fresh conveyance from thence to the place of our destination if it meets with the approbation of Lord Normanby and yourself as it would be very expensive to remain so long in this harbour which I am afraid we shall from all the appearance of the weather at present – if you should wish to communicate to me please to direct any letter to be left at the post office St Ives and I will call there for it on Saturday next providing we should not have sailed and if we should have sailed I will give directions for it to be redirected back to you the prisoners are all well.”

On Thursday 13th February Witheford wrote from Hayle Copperhouse, up the estuary from St Ives, to assure the Home Office that the Usk would be sailing shortly:

“I most respectfully beg leave to inform you: that the weather having moderated, since last night: it is the intention of Captain Parfitt; to leave this Port, next Tide (which will be 12 oClock this Day) in the hopes of being able to get round the Lands’ End to day.

Should we be so fortunate as to succeed, I believe we shall then be able to proceed to our destination without any more stoppages.”

Currently navigating Land’s End was a serious undertaking, all the more so in poor weather. Extremely high seas could obscure the Low Light on the Longships, and the beacon on the Wolf Rock was still in the process of being completed. Still, it seems Captain Parfitt was willing to attempt it. This was just as well, because the Royal Cornwall Gazette reported on Friday 14th February that the Usk and its passengers were attracting attention in Hayle:

“It will be seen by our Shipping List, that the Usk steamer, having on board the Monmouthshire Traitors, Frost, Williams and Jones, has put into this port on her way to Portsmouth. She arrived on Tuesday night; and during the whole day on Wednesday the wharf was crowded with persons from the surrounding neighbourhood, anxious to catch a glimpse of the prisoners. In this, however, they were disappointed, as no one could go on board, and a very strict guard was constantly kept up.”

According to a letter from Truro dated Thursday 13th February, reported in the Bristol Times and Mirror two days later, it was even possible to visit the Usk at Hayle:

“The night before last I arrived at St. Ives, when I saw two steam-boats lying in the bay, and found they were the Herald and Usk, the latter with Frost and Co. on board. They ran for Hayle yesterday morning, where we saw Captain Parfit and Governor Ford of Monmouth Gaol went on board and after sitting in the state room for some time, came from thence without seeing the criminals. They were in the Ladies’ Cabin and kept out of sight by the police on board. Parfitt wished us much to have seen them but could not gratify our curiosity . . . This day after taking in coal &c. they sailed at 12 o’clock for the Land’s End, and, from the favourable state of the weather, we have no doubt will get round to-night. Frost is profoundly serious and requested the use of Captain Parfitt’s Bible. His companion Jones is a most hardened wretch.”

This would not have been what the authorities wanted to see in the newspapers. Four days previously Queen Victoria had married Prince Albert, but the stormy weather had foiled the attempt to remove the Chartist prisoners while the country was distracted by celebrations to mark the wedding. With serious concerns about the progress of the Usk, the Home Office contacted the Admiralty and Captain James Hanway Plumridge, Commander of HMS Astraea, Superintendent of the Packet Service at Falmouth.

A Naval officer who later became an Admiral, Plumridge had political ambitions: having unsuccessfully stood for Parliament in Penryn and Falmouth in the Whig interest in 1837, he won the seat in 1841. In celebration of the Queen’s marriage on Monday 10th February he gave an elegant dinner on board the Astraea for officers of the Packet Service. On Saturday 15th February he wrote with laboured courtesy to Samuel March Phillips in the Secretary of State’s Office at the Home Office:

“So soon as your letter, containing a Copy of a letter to Sir John Barrow of the 13th Instant, came to my hand, I lost no time, and was ready for a start when the second delivery of letters at this Port arrived by which I received their Lordships directions on that head, my reply to which for the Marquiss of Normanbys information, I beg leave to enclose

As a Public Officer it may be proper for me to add that whenever my Port duties will permit of my humble exertions being made available for Her Majestys Service, It will at all times give me satisfaction to have it in my power to comply with your request as emeanating from Her Majestys Secretary of State”

The copy of his letter to Sir John Barrow, Permanent Secretary to the Admiralty, was a more direct account of his actions:

“In obedience to their Lordships direction, I proceeded immediately on the receipt of your letter of the 13th Inst to St Ives; and ascertained on my arrival from the Mayor that the “Usk” started from there on Thursday last.

The Wind has since been moderate, and I imagine ere you receive this letter, their Lordships will have heard of the Usk's arrival at her destination.”

A correspondent at Penzance had seen the prisoners while at sea, reported in the Southern Star on Sunday 16th February:

“The Usk steamer . . . kept in company with the Herald steamer, on their way down Channel; and one of the passengers of the Herald informed me, that the prisoners seemed to be in excellent spirits. He observed at one time Mr. Williams and Mr. Jones playfully going through the manual exercise on deck with a handspike. Mr. Frost appeared to be very thoughtful, sometimes leaning against the side of the vessel, and at others walking the deck for an hour or more, conversing with Mr. Williams.”

On Monday 17th February, no doubt much to the relief of the authorities, the Morning Post was at last able to report the arrival of the Usk at Portsmouth:

“They arrived in good health but in bad spirits – Frost having anxiously inquired if the Queen had extended mercy to them on her marriage. They were immediately transferred to the York hulk and placed in a ward by themselves, which had been prepared for the purpose, so that they may hold no communication with their fellow convicts; and, though they were immediately clothed in convict apparel, they will not be sent on shore to work without further instructions from the Secretary of State’s Office. Under the usual regulation, however, of their letters being unsealed, they will be permitted free communication with their friends; but no one, from idle curiosity, will be suffered to intrude upon them. – Hampshire Telegraph of Saturday.”

There was one further task for the ‘Usk’, to return the army escort to their base. The Monmouthshire Merlin reported on Saturday 22nd February that it had arrived at Chepstow the previous Tuesday. Keen to address any reputational damage to ship or captain caused by reporting of the delays on the voyage to Portsmouth, it added:

“We were much pleased at the appearance of the officer and men, on landing: they looked better than we could have anticipated, after such a boisterous voyage. Great praise is due to Captain Parfitt for his skill and intrepidity in the management of his vessel during the tempestuous weather, and for his kindness and attention to those on board.- A slur having been attempted to be cast, in some quarters, on the inefficiency of the above steamer, from the unusual length of the passage from Cardiff to Portsmouth, it is but right to add that in anything like ordinary weather, her voyages are made with speed and regularity; as a proof of which it may be mentioned that she accomplished the return from Cowes to Chepstow in 44 hours.”

The voyage of the ‘Usk’ taking John Frost, Zephaniah Williams, and William Jones on the first stage of their journey to transportation in Van Diemen’s Land, was completed. It could now resume its routine services.

‘The Cambrian’ 22nd February 1840. National Library of Wales: Welsh Newspapers Online.

* * *

Letters quoted can be found in the Home Office Petitions file for Frost, Williams and Jones, National Archives reference HO18/21. The newspapers are accessible through either Welsh Newspapers Online or the British Newspaper Archive.