60 YEARS OF

"RAPE OF THE

FAIR COUNTRY"

At the 2019 Newport Chartist Convention, Gwent Historian, PETER STRONG marked the 60th Anniversary of the publication of Alexander Cordell’s most successful novel. Dismissed in 1959 as “The Gone with the Wind of the Welsh Valleys” by one of the nation’s foremost literary critics, we are forced to ask sixty years on “Has any other book done so much to spread awareness of the Chartists amongst the people of South Wales?”

At the 2019 Newport Chartist Convention, Gwent Historian, PETER STRONG marked the 60th Anniversary of the publication of Alexander Cordell’s most successful novel. Dismissed in 1959 as “The Gone with the Wind of the Welsh Valleys” by one of the nation’s foremost literary critics, we are forced to ask sixty years on “Has any other book done so much to spread awareness of the Chartists amongst the people of South Wales?”

2019 marked the 60th anniversary of the publication of Alexander Cordell’s Rape of the Fair Country, the story of ironworkers from the town of Blaenafon and the community that had grown up around the forge at nearby Garnddyrys, set during the 1830s and culminating in the Chartist march on Newport in 1839.

In spite of the numerous works by academic historians, it was this book, written not by a historian, and not by a Welshman, but by an English quantity surveyor, that has done more than any other to popularise awareness of the ‘Newport Rising’ and Gwent’s industrial history, not just locally but around the world. A review of a stage performance of the book in 1988 argued that Rape of the Fair Country lies ‘on the Welsh mental bookshelf’ next to the Mabinogion, How Green Was My Valley and the Rothman’s Rugby Year Book’.

Although there had been a number of novels dealing with Welsh working class life before the publication of Rape of the Fair Country, Gwent itself had been poorly served. In 1938 Gwyn Jones, a lecturer in English at Cardiff University and himself ‘one of the leading Anglo-Welsh authors’, gave a talk to Newport Rotary Club. Gwyn was himself a Monmouthshire man - born in New Tredegar, brought up in Blackwood and educated at Tredegar School. He was, much like Alexander Cordell, a socialist and a Welsh nationalist, so his roots and his politics led him to feel affinity with the ‘ordinary working people’ of Wales - and of Monmouthshire, as it then was, in particular.

His talk in Newport was entitled ‘Invisible Exports’ but, more informatively, the report in the Argus was headlined ‘Who Will Write Up Valleys Folk?’ and quoted him as follows:

Those who were born in the valleys will know how, up there, there seemed to be a breed of very rich characters, characters with a sort of racial fat about them. Their humour in a way dripped out of them… Locally you have much material for literature, and it has not really been handled at all. You have these old characters, and you do not find them translated into terms of literature - something happens to so many of them when they are put down in black and white. There has been a very poor attempt to translate Monmouthshire and South Wales into literature.

The Welshmen of literature had always been the most ghastly caricature of the real thing, a ‘Taffy’ who bore no resemblance to the Welshmen, whether half-Welsh or quarter-Welsh…

It is extraordinary what English critics say about books from Wales. It is amazing sometimes to read the ridiculous things they say on the subject. They have no knowledge of the place. They have either an indifference towards it, or a half amused contempt. Consequently the verdicts they pass are valueless in the first place, biased in the second, and ridiculous caricature in the third.

He continued his lecture by pointing out that 17,000 books had been published in Great Britain in 1937, but of those only about thirty or forty were by ‘Anglo-Welshmen’. He regarded four or five of those as ‘outstanding pieces of work,’ identifying in particular David Jones’ war memoir In Parenthesis as ‘undoubtedly one of the best books of the year’. He went on to refer to Jack Jones, the former coal miner from Merthyr Tydfil well known for his novels about the mining communities of Glamorgan, and to criticise the condescending attitude of English reviewers:

‘These Anglo-Welsh writers - pretty good for local boys.’ And they found that Jack Jones was called ‘the miner-novelist’, the criticism implying that ‘he writes novels and they are pretty good too, for a man who has been a miner.’ That is completely wrong… He is probably the best industrial novelist writing in Britain today.

Go back before the War, go back ten years, count out Arthur Machen and W H Davies, and just see how much you have got left. Both those are Monmouthshire men who have brought credit to themselves and their county by their writings about it.

This racy life of the valleys still survives despite the depression.

He did not find unemployed Welshmen

… sitting despondently, hand to brow, gazing vacantly at a coal tip.

You still get there a very resilient character. He is like rubber. You press him down, but as the weight moves he comes back up again - a very distinctive type, so distinctive that there is probably no other place in the British Isles except Ireland, and possibly Lancashire, where you find so distinctive a type, and one who is able to look after himself in voice and in print.

It is high time the infinity of subject of Monmouthshire was brought out and made intelligible to many people who have very queer ideas about it just now. It would be a good thing if these aspects of our native county could be in the form of literature or art given out to other people.

1937 had been a good year for books. Books published included Tolkein’s The Hobbit, Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men, Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not, Agatha Christie’s Death on the Nile and Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier, but apart from In Parenthesis, the only other one listed in the top 200 that could fit the bill as being ‘Anglo-Welsh’ was A J Cronin’s The Citadel. Cronin himself was Scottish but he spent some time working in Tredegar Cottage Hospital in the 1920s and his novel is set in Tredegar. Some people credit it with being an important influence leading to the formation of the NHS.

Interest in the Welsh working class seemed, however, to be growing. 1939 saw publication of How Green Was My Valley by Richard Llewellyn, who in spite of his Welsh name, his Welsh parents, and claiming to have been born in St David’s, was actually born in Middlesex and only spent a short time in Wales. How Green Was My Valley was generally favourably reviewed, although the Birmingham Post seems to have confirmed Gwyn Jones’ comments about English critics when it complained that the dialogue was ‘unrelievedly in the Welsh equivalent of pidgin English.’

It’s unlikely that Alexander Cordell, whose real name was George Alexander Graber, was aware of Gwyn Jones’ lecture. There is no reason why he should have been. Although he had a Welsh-speaking grandmother, he had had little contact with Wales. He had been born in Sri Lanka to an English military family and been brought up mainly in London, with a spell in China, before spending a short spell in the Royal Engineers. In 1937/8 he was working as a quantity surveyor based in Shrewsbury, although his work did take him into the Welsh borderlands.

Over the next few years, however, there were a number of feature films based on working class life in industrial south Wales and Alexander would have been an unusual citizen if he had not seen some if not all of these.

The Citadel, starring Robert Donat was released in 1938, Proud Valley, starring Paul Robeson (and screenplay partly by Jack Jones) in 1940 and How Green Was My Valley, starring Walter Pidgin, Maureen O’Hara and Roddy McDowall in 1941, and Silent Valley in 1943. Silent Valley was very different from the other three, being a 30 minute propaganda piece showing the effect on a mining community if the Nazis conquered Britain. Rather than Hollywood stars, the members of the cast were all local people from the village of Cwmgiedd in the Neath Valley, where the film was set.

It seems very reasonable to suggest that these films may have planted some seeds in young George Graber’s mind; seeds which were to flourish over two decades later.

With the outbreak of war in 1939 he had been recalled to the army and rapidly rose to the rank of sergeant before being sent to France to build pontoon bridges. Following the German blitzkrieg into the Low Countries and France in May 1940 he was evacuated from the Continent via Boulogne, being badly wounded in the legs by shellfire in the process.

This brought him back to Wales, with a long period of convalescence in Harlech, followed by a commission as an officer and a desk job before a posting to Suffolk, where he put his engineering skills to use working on the development of what were known as ‘Hobart’s Funnies’ - new weapons required for the D-Day landings, rising to the rank of major. After being demobbed he had returned to Shrewsbury and a job with the War Office as a quantity surveyor.

Richard Frame and Mike Buckingham (Alexander Cordell UWP Cardiff 1999) explain that Cordell’s first income from writing came from short stories for magazines and that the first one that is known about was called ‘The Gentle Wife’, in Woman’s Weekly in 1950. In an interview with the Argus in 1959 he claimed that his first was called ‘The Diver’s Wife’, which he sold in 1949 for two guineas - enough to take two friends out to dinner. There are, however, copies of three earlier stories held in Newport Reference Library, all published under the name of Alexander Graber. These were ‘Forbidden Territory’, ‘Trouble at Tonkiu’ and ‘Last Voyage’, all set in China and published in the World Wide Magazine for Men in 1947 and 1948. There may be others which have not been traced since he used ‘about four’ different pen names.

At that time he was still living in Shrewsbury, but in 1950 he and his wife moved to the village of Llanellen, near Abergavenny. During the early fifties he seems to have continued concentrating on writing for women’s magazines, selling ‘hundreds’ of stories and even writing a guide for future writers on how to get published in magazines.

By 1954 he had adopted his pen name Alexander Cordell for his first novel, A Thought of Honour, which drew on his wartime experiences. It was not a great success, earning him just £75. The name Cordell was taken from Nobel Prize winner Cordell Hull, who had been American Secretary of State under President Roosevelt and had been one of the founders of the United Nations, a politician admired by both Alexander and his wife.

If Cordell hadn’t seen the report of Gwyn Jones’s lecture in the Argus back in 1938, he certainly saw this advert in the Argus in February 1957 announcing a local history ‘Pages from the Past’ competition run by the Monmouthshire Local History Council and sponsored by the Argus itself, which was putting up a prize of £50.00. According to the advert:

The competition is designed... for amateurs, the man in the street and young people. Individuals, organisations such as religious bodies, schools, trade unions, Young Farmers’ Clubs, Youth Groups, W.I.’s may enter.

They were clearly looking for a substantial piece of work since no limit was placed on length of submissions and, although the entry form had to be returned by 31st March, the entrants had a full year after that to submit their work.

Cordell was no doubt quite excited about this. Since moving to Monmouthshire in 1950 he had spent a lot of time walking and driving around the area either side of the Blorenge, exploring derelict industrial buildings, drinking in local pubs, swapping stories with locals and studying their accents and vocabulary, as well as doing more traditional research in libraries and archives. Here was an ideal opportunity to show off not just his research but also some passages from a novel he was already working on - the novel that was to become Rape of the Fair Country.

His entry, under his own name of G. A. Graber, was finished by July 1957, a full eight months before the closing date. There were over twenty entries and the results were announced in the Argus in June 1958.

He did not win; the winner was a huge study of the history of the town of Monmouth by Keith Kissack. Nevertheless, the Argus did mention his ‘survey… of life among ironworkers at Blaenavon ’ as one of the best six ‘runners up’, although it got his name wrong, identifying him as ‘Major G. A. Graham’.

One reason why he didn’t win was perhaps because his entry was rather different to the standard piece of history writing. As well as the normal material he included various fictionalised passages, which were to appear later in his novel, arguing that each passage was ‘made no less factual by its invention’. This may have rather disconcerted the judges.

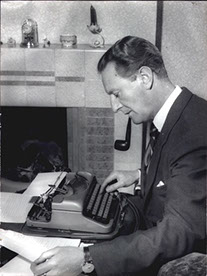

Not discouraged by the fact that he didn’t win, he knew that he had all the necessary material for a novel here and, according to Frame and Buckingham, was able to sit down at his typewriter and rattle it off at great speed. And so it was that in January 1959, Rape of the Fair Country hit the bookshops, published by Victor Gollancz at a price of sixteen shillings.

According to Cordell himself, the title resulted from an encounter with a postman he met on the Blorenge. Looking down towards Blaenafon, Cordell had commented that the landscape had been ‘exploited’ by the process of industrialisation. ‘Exploited!’, the postman replied, ‘This country’s been raped!’ Hoping that the postman would prove a rich seam of source material for his book, he arranged to meet him the next evening in a pub. When he arrived, there was no sign of him. Upon asking a group of men in the pub if they had seen him, they told him that he had died the previous evening. Cordell went on to put his words into Iestyn Mortymer’s mouth: ‘Plundered is my country, violated, raped.’

Inside the front and back covers of his ‘Pages from the Past’ entry he pasted a photograph of an old man, presumably a miner or ironworker, with Blaenafon in the background. He also refers to talking to a 91 year old miner; not necessarily the same person but certainly symbolic of him and many others who provided him with inspiration and information.

Upon publication, the book caused an immediate flurry. His publishers had served him well, doing the groundwork to get advance publicity and reviews in local, national and even American newspapers and from prominent individuals including Nye Bevan, J.B. Priestley, and the playwright Emlyn Williams. It was especially well received by left-wing newspapers, being recommended by the Daily Worker, while the Labour-supporting Daily Herald called it ‘a slap in the face for anyone who has become complacent about the conditions under which quite a few people still have to work.’ and gave it high praise, although the reviewer erroneously stated that it ended with a march on Monmouth rather than Newport.

At the end of the year, the Times listed it as one of the novels of 1959. It had a lot of competition. 1959 was another good year for novels. New publications that year had included Alan Sillitoe’s Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, Laurie Lee’s Cider With Rosie, Keith Waterhouse’s Billy Liar, and E H Braithwaite’s To Sir With Love. It’s noticeable how all of these, like Rape of the Fair Country, sought to portray working class life and had strong regional identities - Nottingham, Gloucestershire, Yorkshire and the East End of London. So Alexander was very much ‘on trend’.

Not all reviewers were entirely impressed. The leading Welsh academic and journalist Goronwy Rees, writing in the Listener, argued that it did not live up to the publisher’s hype, being ‘simply a historical novel of the straightforward best-selling variety’ and called it ‘the Gone with the Wind of the Welsh Valleys’. Brian Aldiss, who was soon to achieve fame as a science fiction writer, writing in the Oxford Mail, also saw it in terms of Hollywood:

… its model is too obviously those big American sagas about the Good Bad Old Days. Even its title must have been chosen with one eye on VistaVision.

The Tatler expressed its criticism in a tone which could be seen as demonstrating the points about English reviewers made by Gwyn Jones back in 1938:

In spite of the concerted Welsh shout of praise given away with Rape of the Fair Country, by Alexander Cordell, and in spite of the fact that it is good story-telling and full of drama, I found it somehow a touch souped-up, too much the wild, passionate, prose-poetry Wales of pop fiction. The climate of the iron furnaces and the grinding poverty of the 1830s in Wales reads true enough, and it seems mean to be sour-faced about all that picturesque Welshy-English dialogue with a few basic phrases in real live Welsh to add colour, and lots of passion in great big beds. Ah, those mad, crazy, proud Welsh, what a boon they've been to novelists.

But it was naturally in South Wales that it had its greatest impact. The week before Rape of the Fair Country was published, a lecture was given in Newport, which seemed to echo what Gwyn Jones had argued in his lecture 21 years previously. Jack Jones, the Welsh novelist who Gwyn had mentioned in his lecture, spoke to the local branch of the Welsh Graduates Guild, arguing that:

This town of Newport and the county of Monmouthshire deserve to be placed securely on the map of fiction. But this place has never yet received full justice from creative artists and it’s time that it did. An epic novel could be written about Newport, its expansion and extension of industry, relating it to Newport of the past.

During the last quarter of a century in his tours of Monmouthshire he had discovered many sons and daughters who had literary ambitions and who wanted to write about their county in much the same way as he had written about South Wales. But an Englishman had beaten them to it. He was Alexander Cordell, now living in Abergavenny whose latest novel, Rape of the Fair Country was to be published next week. The author caught the spirit of the valleys and wrote a novel worthy of them. It is a fine tribute to those who lived and worked in those valleys long ago.

The Argus also loved it. Roland Chambers, an Argus staff reporter, emphasised the powerful nature of the story:

Centring on the fictitious Mortymer family of Garndyrus near Abergavenny, this book tells the true (sic) story of the shocking social conditions of the time when labour for the English ironmasters was cheap, but life and limb were cheaper.

It tells of a time when 4d a week earned by a child made a great difference to the living conditions of a family. It deals with men and children, boys and girls, maimed and killed by metal splash, and it tells of a family who, during a strike, were so near starvation they roasted a dog for the Sunday dinner and convinced the children it was chicken.

He went on to praise the way in which Cordell had ‘thoroughly mastered the Monmouthshire idiom’ and ‘the strong vein of bawdy humour’ which went alongside the ‘the tenderness and great depth of feeling’ and described his portrayals of the rural landscape as ‘comparable to the finest descriptions I have read of Monmouthshire’.

But he warned that it was ‘… not for the squeamish. Cordell pulls no punches. There is a savagery in his expression and he swears powerfully and often.’ What counted as ‘powerful swearing’ in 1959 was pretty mild compared to today. Many years later Cordell was angry to find that in one of his novels an editor had tried to change ‘bloody’ for the f-word - a word he would never dream of using in print.

It may be that Chambers got a bit carried away with enthusiasm in asserting that it was ‘becoming one of the greatest literary achievements of the century.’

The Western Mail got into the act ten days in advance of publication, predicting quite correctly that it would ‘cause something of a stir in the literary world’, although it did, incorrectly, state that the novel was partly set in north-east Glamorgan, misspelt the name Mortymer (as Mortimer) and got some details of Cordell’s army career wrong (saying he was a major at the start of the war and implying that he was demobbed after being wounded at Dunkirk).

The Western Mail review upon publication was headlined ‘Epic Novel of Anger in the Valleys’ and described it as ‘having enough punch in it to make a hundred of the pallid things that pass for historical novels nowadays,’ but warned that ‘some may find the frank sexuality of many passages an embarrassment’, although the reviewer argued that this was ‘essential to give the complete picture of the people Mr Cordell wants us to understand.’ Six days later it ran an interview which sought to contrast the ‘quiet conventional Englishman with a typical suburban home’ who even looked English - ‘tall, blond, long in the head and reticently moustached’ - with the violence, emotion and thoroughgoing Welshness of his subject matter.

All this is particularly remarkable when it is remembered that the Western Mail at the time was an openly Conservative newspaper which had historically been known as the mouthpiece of the Welsh coal owners. The same page that carried the interview with Cordell had an article and a letter hostile to Labour’s plans for nationalisation of steel and the interviewer himself showed his own political leanings by pointing out that although Cordell would make a lot of money from the book, ‘the Inland Revenue will scythe him to the bone’. Perhaps even more remarkably, the Western Mail actually serialised the book, with each episode accompanied by an illustration.

Not surprisingly, there was a reaction to all this praise - not so much from a literary point of view but from the political and historical. Shortly after publication, the Argus printed an article headed ‘Unfair to the Crawshays’ in which William Crawshay of Llanfair Court , near Abergavenny, a ‘ direct descendent of the ironmasters of Cyfarthfa’ commented that ‘one could drive cart horses through the holes in the references in this book’.

One of his characters says he can remember the ironworks from Anthony Bacon’s day right down to Robert Crawshay. If he had been able to do that he would have been 120 years old.

My grandfather lived at Cyfarthfa and it was my great grandfather to whom Graber referred - Robert Thompson Crawshay. Graber gets in wrong and calls him Robert Thomas Crawshay.

The Western Mail commissioned Lionel Williams, a history lecturer at Cardiff University, to answer the question of whether Cordell had been fair to the ironmasters. He started off in critical mode, arguing that ‘events, which even to the detached historian, appear dramatic, tend in Mr Cordell’s novel to emerge as black-and-white melodrama …’ He also challenged the idea, implicit in the title Rape of the Fair Country, that Wales before the arrival of the English iron masters was some sort of rural idyll: ‘South-east Wales in 1759, so far from being a rural paradise, was a poor land, lacking both the capital and the expertise with which to develop its resources.’ He also pointed out that the ironmasters faced many problems including shortage of capital, a protracted period of depression lasting from the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 until the railway boom of 1843 onwards, and fierce price competition. On top of that, as their works grew, they increasingly relinquished direct control to sub-contractors, who weren’t sufficiently supervised. This was particularly apparent in the operation of the truck system:

Symbolic of the widening gulf between masters and men was the building of Cyfarthfa Castle by William Crawshay II in… 1825. Such an example of ‘conspicuous consumption’, harmless in itself (and deplored by William Crawshay I), tended to undermine the ironmasters’ attempts to inculcate in their workers those habits of thrift and hard continuous work to which they attributed their success.

Labour costs must become a calculable factor in production costs, therefore (they argued) wages must depend upon the selling price of iron. That wages might then fluctuate violently within a short period was an unpleasant economic necessity.

A significantly increasing number of workers, however, regarded this as a cruel and heartless exploitation.

In the end he agrees with the statement made by Hywel Mortymer, Iestyn’s father, in the novel: ‘The ironmasters may seem born of the devil, but they are not without character, nor are they short of their troubles’.

Much the same view was expressed by Cordell himself in his 1957 ‘Pages from the Past’ study:

A work of history should hold no preferences, yet the very subject of this title - the ironworkers - and the telling of their conditions of living automatically places the masters in a poor light. Few masters of the early 19th century were blameless by modern standards, but they were not without their difficulties … The masters of the Twin Towns, especially Samuel Hopkins, showed a degree of charity and justice that compared well with any other iron town on the Top… Commercial competition was acute. The Big Brothers of the industry, men like Sir John Guest of Dowlais, Richard Crawshay of Cyfarthfa and Crawshay and Joseph Bailey of Nantyglo, were competing for markets and power, the Crawshays very much at the expense of their workers.

Elsewhere in the same study he described Hopkins as ‘a good master’, pointing out that he built St Peter’s Church and that his sister built the school, while ‘Crawshay (Bailey) ground the last ounce from his workers and had little interest in their spiritual or physical welfare.’

As might be expected, those who wrote into the Western Mail were not so nuanced. T. J. Southall of Penarth regarded it as ‘a piece of historical sensationalism dealing with a period which everyone is ashamed of, and would much rather forget. Nothing good can grow out of bitterness.’ Mrs Sara Rowe of Solva, Pembrokeshire, complained that Cordell had portrayed things ‘as if all the working class lived and acted like gross and unintelligent brutes.’

Gwen Langston from Kington, sprang to the defence of the ironmasters:

Rape of the Fair Country must be offensive to descendants to the Crawshay family and many others. The Crawshays made their way up from the bottom rung by their own grit and ‘sweat’ and put South Wales on the map by initiating its industrialisation. Possibly in a hundred years hence, or even less, another Cordell will rise to write of the living conditions of the present generation under similar cheap ‘selling colours’. This will be equally sordid reading, compared with what will then be the accepted standard of living.

This prompted a reply from Mr Etienne Raven of Cardiff, who argued that Cordell was right to point out that ‘those who made fortunes from industrialism were the industrialists, not the creators of wealth’ by which he meant the workers, and that if the novel was ‘sordid’ it was because that was what life was like. Relating his point to the coal rather than the iron industry he went on:

At a time when Cardiff was exporting 13 million tons of coal annually… it was not the coal magnate who lived on the side of a mountain and whose major reward for “grit and sweat” was an empty stomach, blue scars and crumbling lungs.

Mr Burke from Merthyr supported Cordell’s idea of the ‘rape’ of South Wales, drawing attention to Merthyr’s ‘ruined natural assets’:

The heaps of crumbling brick, the gaunt limestone furnace complexes, the broken rusty slag moulds. All speak eloquently of the greed that wrested the wealth from the land, only to leave filth and debris scattered with monumental indifference about the ‘fair country’.

An objection of a different kind came from Mr H. Jenkins of Tredegar, who stopped reading the serialisation after the instalment that described the ‘mating of Dai Two’, the pig that the Mortymers kept in their back yard. Cordell had described in some detail the scene when she is taken to a local boar but tries to run away, eventually disappearing into a dung heap, only to be pursued, caught and serviced by her amorous partner in front of a cheering crowd. Mr Jenkins regarded this as ‘crude and distasteful in the extreme’.

The last word in this sequence of correspondence was had by Mr Hugh Williams, Joint Secretary of the Nantyglo and Blaina Historical Society. Sensibly, he pointed out that it was wrong to assume that a novel should be regarded as a factual historical narrative. He praised Cordell’s research but raised the possibility that in his criticism of the ironmasters he had been ‘influenced excessively’ by David Williams’ biography of John Frost and Ness Edwards’ history of Chartism, the latter in particular being written from a left-wing perspective, before going on to argue that in his portrayal of working class life in industrial Wales ‘there is certainly the imprint of the “Saesneg” commissioners report in Rape of the Fair Country ‘. This was a reference to the notorious ‘blue books’, the 1847 report of the government enquiry into the state of education in Wales in which English commissioners, who spoke no Welsh and relied excessively on the evidence of Anglican clergymen, portrayed the Welsh as backwards, drunken and immoral.

At this point the editor intervened with the inevitable, ‘This correspondence is now closed .’

The criticisms seemed to have no negative impact on sales. Within six months it had run to five editions and by the end of the year had been published in the USA and eight European countries, bringing in a substantial income. It had been listed as second in the list of the top novels of 1959 by the New York Times. Cordell had also finished the sequel, which he initially called Cry of the Fair People but was published in August 1960 as The Hosts of Rebecca, which is narrated by Iestyn’s younger brother Jethro and in which the Mortymers, having moved away from Gwent, find themselves mixed up in the Rebecca Riots in Carmarthenshire. At this stage Cordell was still working as a Quantity Surveyor and in spite of continued success with his subsequent novels, didn’t give up the day job until the late 1960s.

One reason why most of the other books from 1959 listed above became so well-known was because they were made into very popular films (or in the case of Cider With Rosie, a television production). As noted above, Rape of the Fair Country seemed ideal for turning into a Hollywood blockbuster and there were various attempts to get a film project off the ground. In December 1968, for example, the Daily Mirror reported on its front page that 18 year old Welsh singer Mary Hopkin was being offered a starring role in a film of the book to be made by actor Stanley Baker. It was, however, never made into a film, largely because of ‘creative differences’ between Cordell and the film companies, although there have been several theatre productions. Given that the Mirror summarised the book as ‘the story of a Welsh girl’s first passionate love affair’, it’s perhaps easy to see how ‘creative differences’ emerged.

Even though Cordell’s later novels covered other parts of Wales and ranged around from Spain to China, and although he eventually moved away from south Wales, he kept coming back to Monmouthshire and particularly to the Chartists and to the Mortymers. Even while Rape of the Fair Country was still at the printers he had been persuaded by his wife to write a short Chartist play - Tea at Pie(sic) Corner - for Abergavenny Women’s Institute Drama Festival. In November he wrote a review of Asa Briggs’ book Chartist Studies for the Western Mail. In 1969 the third in what was then the Mortymer trilogy was published. Song of the Earth featured Mari Mortymer, wife of Iestyn, and is largely set amongst the bargees on the Neath Canal.

In 1985 he unveiled a plaque on the quayside at Chepstow to mark the spot where Frost, Williams and Jones, having been brought by road from Monmouth gaol, were put on board a ship en route for the prison hulks in Portsmouth and from there to Van Diemen’s Land. In 1987 he published a prequel to Rape of the Fair Country, This Proud and Savage Land, which tells the early story of Hywel Mortymer, Iestyn’s father.

1988 Alexander Cordell with Cllr V. Brydon, Mayor of Newport

On 4th November 1988, he unveiled a memorial stone to the dead Chartists who were buried in St Woolos Churchyard and then marched down Stow Hill to the ballroom of the Westgate Hotel where, supervised by red-coated toastmaster Harry Poloway, with a harpist playing on the balcony and the Mayor of Newport present, he launched Requiem for a Patriot, a fictionalised account of the life of John Frost. This, in his view, was the ultimate symbol of the Chartist victory.

The following year, being the 150th anniversary of the rising, he wrote a piece for Newport Local History Society’s special edition newsletter. In 1993 he wrote another sequel to Rape of the Fair Country, Beloved Exile, in which Iestyn is exiled for his part in the Chartist Rising, eventually returning to Wales after many years in Afghanistan, and in 1997 rounded off the story of the Mortymers in The Love That God Forgot, set in the 1880s, by which time Iestyn had become a wealthy industrialist and in which his son runs off to live on Flatholm.

Alexander Cordell died later in 1997. By this time he had almost 30 novels to his name, written over a period of over 40 years, although it is fair to say that none reached the heights of Rape of the Fair Country.

Buckingham and Frame called Rape of the Fair Country ‘the greatest book of imagination ever to be written in and about Gwent’ and observed that while marching down Stow Hill following a ceremony at St Woolos Cathedral, Cordell was ‘beaming proudly, fully convinced of the fact that it was largely due to his literary efforts that the Chartists were being remembered at all.’

Not everybody would go this far, but whatever its strengths and weaknesses as a work of history and literature, it can be safely argued that few other publications have done more to spread awareness amongst the people of south Wales of the Chartist Movement and its place in our history and that few people have done more than Alexander Cordell to inspire budding local historians in Gwent to delve more deeply into the area’s industrial past and unlock its secrets.

REFERENCES

G A Graber, ‘Life Among the Ironworkers of Garndyrus and Blaenavon 1810-1836’, manuscript copy Newport Reference Library.

Mike Buckingham and Richard Frame, Alexander Cordell UWP Cardiff 1999.

SWWA: South Wales Weekly Argus.

WM: Western Mail

See also

Chris Barber, In the Footsteps of Alexander Cordell, Blorenge Books Llanfoist 2007.

Chris Barber, Cordell Country, Blorenge Books Llanfoist 1985.

“Sailing Directions for the Bristol Channel” compiled by E J Bedford 1884 (British Library)