Henry Vincent

The Monmouth Prison Letters

Peter Strong writes:

On May 8th 1839, Henry Vincent, founder member of the Chartist Convention, Chartist missionary to the west of England and South Wales and editor of the Chartist newspaper, the Western Vindicator, was arrested in London on a warrant issued by Newport magistrates on a charge of “having conspired to produce discontent and unlawful assembly”. (Northern Star, 18 May 1839)

He was taken to Newport and after a brief hearing at the King’s Head, and having failed to meet the impossibly high bail terms imposed by the magistrates, transferred to the County Prison at Monmouth pending the next Assizes. He was held there for five and a half weeks before being briefly released after a hearing in London in which a judge in chambers ruled that the bail terms were excessive. (Monmouthshire Beacon, 29 June1839)

On August 2nd he was tried along with William Townsend, John Dickenson and William Edwards, at the Monmouthshire Assizes, held at the Shire Hall, Monmouth, found guilty, sentenced to a year in prison and returned to Monmouth gaol. This of course meant that he was in prison at the time of the Newport Rising, probably saving him from the same fate as Frost, Williams and Jones.

On March 30th 1840, while still in prison, he, along with William Edwards, was tried again on grounds that they had ‘entered into a conspiracy with intent by force and unlawful means to cause a great change in the government’ and sentenced to a further year.(Monmouthshire Beacon, 4 April 1840)

He was transferred from Monmouth to the Millbank Penitentiary in London, where he spent a month before being transferred again, this time to the Rutland County Prison in the town of Oakham, where he remained for another seven months before being released in January 1841. (For a biography of Vincent see William Dorling, Henry Vincent: A Biographical Sketch London: Garland, 1897.)

In 1965 an article ‘The Prisoner in Monmouth Jail: A Study of Henry Vincent (1813-1878)’ appeared in Presenting Monmouthshire, the forerunner of Gwent Local History, journal of the Gwent County History Association. It’s author, Clifford Tucker, had pieced together a highly informative biography of Vincent based entirely on secondary sources. (Presenting Monmouthshire No 20 (Autumn 1965) p.17-27. Two further articles on Vincent, by Gareth Rogers, appeared in Presenting Monmouthshire (No 30,and No 31) in 1970 and 1971. These contain no references but appear to be based on Dorling and on a report of the first of Vincent’s two trials.)

The article made a number of comments about Vincent’s time in jail, but contained no testimony from Vincent himself made during his confinement. Tucker was almost certainly unaware that lurking in the archives of the Labour Party in Transport House, London, was a series of letters written by Vincent, including 13 from Monmouth Gaol and 18 from the Rutland County Gaol.

These letters were later transferred to the People’s History Museum in Manchester. (People’s History Museum, Manchester, VIN 1/1/14-1/1/27 (Monmouth), VIN 1/1/28-1/1/45 (Oakham). There are also 13 letters written between August 1837 and November 1838 (VIN 1/1/1-1/1/13, before his time in prison, and six written after his release in 1841 (VIN 1/1/46-1/1/51). This article is based on photocopies held by Les James. I am grateful to him for allowing me to borrow and transcribe them.

They were written to Vincent’s close friend John Minikin, who lived at Covent Garden. Little is known about Miniken (variously spelt Minnikin, Minikin The letters are addressed to him at 14 New Cavendish Street and the Cambrian Hotel, Great Russell Street, London. The Shipping and Mercantile Gazette, 8th February 1841, describes him as a coffee-house keeper in Great Russell Street, Covent Garden.

While the content of these letters are not earth shattering, they do give us a deeper insight into this important figure in the Chartist Movement, not only into his treatment in prison but also into his contacts with the outside world, his attitudes, his preparations for his trials and his views on various matters.

Using these letters presents a number of difficulties. Vincent’s handwriting is not always the clearest and some words are indecipherable. He also makes a number of references to obscure pieces of poetry or talks in cryptic terms, making it sometimes difficult to grasp what he is trying to day or whether he is being ironic. For example in his first letter from Monmouth gaol he wrote: “Here I am safely located in this Mansion –one of the cleanest and most comfortable buildings I have ever seen.” (VIN 1/1/14, 15 May 1839.)

Writing from custody, he could not always express himself freely. In his second letter from custody, he took a rather mocking view of the censorship of the letters he sent and received:

“We grumbling radicals cannot so much as write a love ditty to a lovesick damsel without having our soft tale perused … But it is very proper your letters should be read before they reach me –because being such an outrageous Rad and a philosopher to boot you might appraise me of some incantation a la fortunatos which would, by enchantment, convey me from my midnight cell.”

(VIN 1/1/15, 21 May 1839)

It seems that some of his letters were smuggled out and others taken out by his solicitor, J G H Owen:

“I wrote this to you privately, so if you ever write to the gaol you must not notice it (i.e. make mention of it –PS). If you wish to write to me address your letter to Mr Owen, Solicitor, Monmouth …” (VIN 1/1/22, n.d. Feb 1840)

On 28th February:

“I was obliged to burn your letter for fear it would be discovered. I send this to mother… have not had the opportunity of writing before; two letters to you I have been reluctantly compelled to burn, and there is one in the hands of the government written two months ago., which the magistrate would not allow to be sent.” (VIN 1/1/23, 28 February 1840)

And on 5th March:

“Let me have a letter by return of post, if it be ever so short, addressed to Mr Owen, Solicitor, Monmouth, Monmouthshire. Do not put any names on the outside, put mine on the inside and put Owen’s address on the envelope. I do not wish my name to appear at the Post Office.” (VIN 1/1/24, 5 March 1840)

But also in the same letter, more intriguingly: “I never get anything smuggled in. Understand that (?)” (Question mark in the original.) (VIN 1/1/24, 5 March 1840)

Does he actually mean that nothing ever gets smuggled in to him or is trying to throw the censor off the scent?

Some of what he writes, relates to personal and family issues. This for example:

“I was, I must confess, grieved to hear of the death of poor Jane (his young sister -PS), though I felt it to be a happy release both for her and mother .. I cannot but feel thankful that her miseries are over. I hope mother will get rest during the summer and endeavour to rally her own health.” (VIN 1/1/22, n.d. Feb 1840)

CONDITIONS AND TREATMENT IN JAIL

His third letter (1st June 1839) responds in some detail to Minikin’s request for a description of the gaol. From this we can tell that Vincent, Edwards and Dickinson were far better off than other inmates, perhaps because there was a tacit recognition that they were political prisoners.

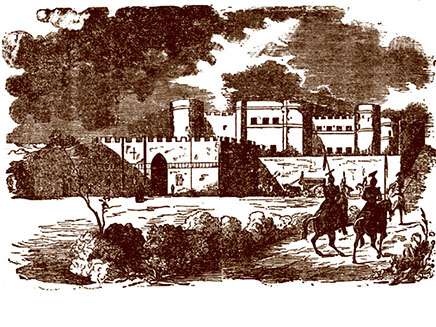

“Monmouth Gaol is a fine castlefied looking building on a rather elevated position … It is in a very healthy position, and…the scenery around is very delightful. A muddy river which empties itself into the Severn runs near the gaol. The portion of this building in which myself and two friends reside consists of a small room about 8 yards square and 13 ft high, stone floor and a stone seat along one side of the wall; it contains a fire-place and two wooden shelves upon which we place our books, clean linen etc.

Descending three steps, we have a large quad surrounded by walls, in which we walk at pleasure. The yard is about 20 yards long and about 10 yards wide...We sleep in separate bedrooms…The night rooms are small, with stone floors and iron doors. The windows are high, pailed with irons and a board placed up on the outside which prevents us having a view of the beautiful fields, for there are beautiful fields and trees, without, and the sweet melody of the nightbird lulls me to sleep at night, and the merry lark, and the melow (sic) toned blackbird awakes me at early morning. The bedstead is iron, the bed a straw one, the bedding course but very clean.”

(VIN 1/1/16, 1 Jun 1839)

They were able to make things a bit more comfortable for themselves by borrowing a wooden table and two rough made wooden stools

The prison food was pretty unbearable, comprising a daily allowance of “one pound of potatoes, two quarts of skilly, salt not limited!” (VIN 1/1/16, 1 June 1839)

Fortunately, however, they did not have to rely purely on this:

“ …we have purchased coffee pot, kettle, saucepan, gridiron, frying pan, cups, saucers, plates, knives, forks, spoons etc. … We purchase our own food, but we have had several presents, and now we have hung up in our little kitchen a fine ham and half a side of bacon, and, at present, we have a very plentiful supply of tea, lump and mist sugar, coffee etc, which have been sent to us from Bath, Bristol, __________, Newport and other places.” (VIN 1/1/16, 1 Jun 1839)

They also had clothes sent in from outside:

“…if either you or any other friends wish to know how we look you must come and have a squint at us through the iron bars of our prison. You will find me in our stilish (sic) morning gown sent to me by a pretty little lassie (God bless her); with a paper cap, cut a-la-Napoleon, and sundry other nick-nacks…”

He goes on to describe the daily routine:

“At six in the morning the gaol bell rings; that is the signal for rising. Out of bed we jump, partly dress ourselves, and in a few minutes we hear the rattling of chains and the squeaking of the locks of doors, occasioned by the turnkeys unkennelling the prisoners. They appear to let us out at last. We get down into the yard a little after six, wash ourselves clean, brush our boots and clothing, and wake up and down the yard, while one prepares breakfast, which generally consists of coffee, a rasher of bacon, and bread and butter. We breakfast at ½ past 7. We then clear the table and read and write until nearly one o’clock. Dinner is next prepared in the shape of a second breakfast. After which, sometimes I sing a few songs. Then we walk up and down the yard for a while and take our stools into the sunny yard and read there for an hour or two. Five o’clock, we take a little tea, read or write again, and from half past six till half past seven walk up and down the yard. Between half past seven and eight the bell rings and we are taken up flights of stone stairs, through several heavy iron doors to our beds and when we are locked in our bed-cells the turnkey retires locking all the doors through which we passed. I always take a book up to bed with me, and my favourite bird the lark wakes me every morning before 4 o’clock; so that I get two hours good reading time before six o’clock every morning. I have several of Cobbett’s works and I am reaping much instruction therefrom.”

They also gained some diversion from a fellow prisoner:

“Besides myself, Townsend and Edwards, we have a Welshman, a hard worker, with us all day. He is put in here because someone has insinuated that he has got two wives all alive o! –and here he is waiting until the Monmouth Assizes! He could neither read or write. We have provided him with spelling book and copybook and he is making wonderful progress under us as a reader and writer.” (VIN 1/1/16, 1 June 1839)

The ‘Welshman’ was 26 year old Thomas Jones of Tredegar. He appeared at the same Assizes as Vincent on 2nd August, charged with bigamy. It was noted that he could not read or write but at the trial a letter written in Vincent’s handwriting but signed by Thomas Jones and forwarded to the court by Charles Ford, the prison governor, which explained that while in prison ‘the Chartists’ gad been teaching him to read and write. He was found guilty and sentenced to one year’s hard labour in the House of Correction at Usk, which the judge observed would give him the opportunity to continue his education. (Monmouthshire Merlin, 3 August 1839)

Conditions did seem to get worse after he was tried and sentenced, although he only makes a couple of brief references to this, both in February 1840:

“You should see me, Minikin, taking my daily mess of skilly, rotten potatoes and bad bread.” (VIN 1/1/21, 15 Feb 1840)

“So here I am, my friend, sitting on a three legged wooden stool…” (VIN 1/1/22 n.d., Feb 1840)

Nevertheless, all in all, in the early stages at least, he accepted imprisonment in good spirits and as presenting certain opportunities:

“…there is but little doubt that I shall make an effort to climb the steep hill of improvement.” (VIN 1/1/15, 21 May 1839)

According to his letters, what Vincent found most unpleasant about prison life was the compulsory religious services:

“On Wednesday and Friday mornings the bell is rung at ½ past nine as a signal for our going up into the Church to have read over us the miserably humdrum service of the “Protestant Church as by Law Established”. Our minister is a very worthy and gentlemanly man, and appears the most worthy Church clergyman I ever met with. He appears rather intelligent. … Yes, every Wednesday and Friday morning to have (prayers to) ‘the Lord’s spiritual and temporal,’ ‘our high court of Parliament’, ‘Your Dowager Adelaide and all the royal family’, including of course Sallis Cumberland…” (This is a reference to a scandal back in 1810 when Joseph Sallis, valet of the Duke of Cumberland, was found with his throat cut at the Duke’s home. There were persistent rumours that the Duke was responsible.)

“… yes, every Wednesday and Friday all this stuff is crammed into me, and it tastes like so much sour crout (sic). Ditto twice on Sunday, ditto!”

(The reference to ‘sour crout ’ relates to the Duke being German and having become King of Hanover.)

On religious matters, Vincent’s own views aligned with the more radical wing of non-conformity, who in his mind had much the better preachers: “You and I who have heard the glorious Fox lecture to us in Finsbury Chapel on a Sunday morning know well what this church rubbish is.” (Vin 1/1/16, 1 Jun 1839)

Fox was William Johnson Fox, a Unitarian Minister based at Finsbury Chapel. The chapel became well known for its association with progressive causes, including feminism, Chartism and anti-slavery. (https://humanistheritage.org.uk/articles/william-johnson-fox)

After witnessing the minister’s attitude to Frost, Williams and Jones, who were in the same gaol after the Newport Rising, Vincent’s attitude becomes even more hostile:

After witnessing the minister’s attitude to Frost, Williams and Jones, who were in the same gaol after the Newport Rising, Vincent’s attitude becomes even more hostile:

“Our parson seemed much disappointed that they were not hung. We call him the gravedigger and ropemaker, for he was digging graves and making ropes in every sermon he preached while Frost was here.” (VIN 1/1/21, 15 Feb 1840)

By contrast, Henry seems to have got on well with the chief turnkey, James Evans. In his first letter from Oakham he asks Minikin to write to him at the Lodge, Monmouth Gaol to send “kindest regards to him and his wife.” (VIN 1/1/28, 12 Jun 1840)

CONTACT WITH THE OUTSIDE WORLD

Clearly Vincent was keen to know as much as possible about what was happening ‘on the outside’. In his second letter he appealed to Minikin to “let me have all the news, tales, scandals etc.” (VIN 1/1/15, 21 May 1839)

Unfortunately, we don’t have Minikin’s letters in reply to Vincent, so we don’t have details of the “scandals”, although he did thank Minikin for the information he supplied.

He was also able to receive visitors. In June 1839, he reported that he was expecting a visit from John Frost and he also had visits from his legal representatives, including W.P. Roberts, the radical lawyer from Bath and J G H Owen from Monmouth. (VIN 1/1/16, 1 Jun 1839)

In February 1840, after Frost, Williams and Jones had been transported, but before his own second trial, he wrote that

“Roberts was here from Bath yesterday. Upon my soul he is a good fellow. He obtained permission to sit with me (as a lawyer) in the company of my friend Mr Owen for two hours. You may easily imagine that I enjoy the treat. He speaks very highly of the state of feeling in and around the beautiful city of Bath.” (VIN 1/1/23, 28 Feb 1840 )

Shortly after, however, Roberts himself, along with William Carrier of Trowbridge was sent to prison for his part in the Chartist agitation in Wiltshire, leaving Vincent somewhat shocked:

“I hear that Carrier has to perform hard labour for two years. Come, this beats every preceeding villainy. Hard labour for political offences! What next? Pillory or the scourge! The inhuman devils! Right glad am I that I was not at Salisbury. I very much fear that two years will be the death of Roberts. He has been used to high living and every conceivable comfort. Poor fellow! … He is an honestly devoted friend of Liberty. What makes matters still worse, he has a new wife. She will doubtless grieve much. Roberts is a brave fellow and will bear it like a man.” (VIN 1/1/26, 20 March 1840)

ACCESS TO NEWSPAPERS

Perhaps the one thing that Vincent most valued in terms of contact with the outside world and which made his life in prison bearable was the fact that he was able to receive newspapers. In his first letter to Minikin from Monmouth gaol he writes:

“…send me the Times newspaper, with the account of our Newport examination, with any other account that may have been published in the London papers.” (VIN 1/1/14, 14 May 1839)

He clearly received papers, since in his next letter he wrote:

“Thanks for several London newspapers, for I suppose you send them, although I do not see the directions, the covers being taken off before they reach me.” (VIN 1/1/15, 21 May 1839)

To some extent, it was a two way process. Thus, on 19 May, just over a week after his arrest, he wrote a letter to the Northern Star, Chartist newspaper, which was published on 25th May with a reply from Feargus O’Connor.

Obviously, what most interested him was stories about himself. Thus, on 5th March 1840:

“Do you see the Northern Star? A full length portrait of me is shortly to be given away with it. I regret that there is no correct likeness of me published. I wish you would get me one each of the several that have appeared and send them under cover of Mr Owen for me.” (VIN 1/1/24, 5 March 1840)

CONTACT WITH FROST, WILLIAMS AND JONES

Obviously, news of the Newport Rising reached Vincent in Monmouth gaol, although disappointingly, he has virtually nothing to say about it, probably constrained by the censor and the need to avoid giving any ammunition to the prosecution of Frost, Williams, Jones and the other Chartists.

It’s very noticeable that there is a long gap -6½ months- in the letters between 31st July 1839 and 15th February 1840, the period which covered his own first trial in August, the Rising in November, the trial of Frost etc in January and their removal from Monmouth at the beginning of February.

All we get is a cryptic comment written four months after the Rising: “A mishap happened 4 months since, which I shall some day make you acquainted with.” (VIN 1/1/23, 28 Feb 1840)

We have already noted that while he was still a free man Frost seems may have visited Vincent in gaol. He also saw him after his conviction, as he noted in a letter written two weeks after Frost, Williams and Jones were removed from Monmouth en route for van Diemen’s Land: “I saw F. privately when he was here. I hope they will have a free pardon. I think they will.” (VIN 1/1/21, 15th February 1840)

After that we get just two more references to Frost:

“I hope Frost and the others will, in spite of all, be yet restored to liberty. I love Frost for his love of his country! He is really a good man.” (VIN 1/1/23, 28 Feb 1840)

“I have heard that John Frost is gone. Poor fellow! Though, if he lives, I by no means despair of seeing him again. He is one of the few really honest men that I have had the pleasure of knowing. While he is banished … he has a claim on my every exertion. Good, organised and perpetual agitation will yet restore him to the land of his birth. Both Jones and Williams are excellent men. God grant that I may live to see them again.” (VIN 1/1/24, 5 March 1840)

I think the comment about Frost loving his country (by which I assume he means Britain rather than specifically Wales) is significant since it does illustrate the strongly patriotic trend that seems to me to have been central to Chartism.

HEALTH

His period in custody and the strain of facing two trials in Monmouth, plus the prospect of further prosecution at the hands of the Wiltshire magistrates, naturally took a toll on his health, and there are several references to this in the Monmouth letters:

In February 1840:

“My health is very good, the first three months tried me severely, but after taking about a bucket full of medicine, and taking up my station in the infirmary for a few days, I have weathered the storm.” (VIN 1/1/22, n.d. February 1840)

But a few weeks later:

“I am much better than I was when I last wrote you. The doctor here behaved exceedingly well. He wrote to the Counsel for the Wiltshire prosecution, stating that I was not in a condition to be removed. Although a Tory, the doctor is one of the most humane and intelligent men it has ever been my good faith to meet with … Since I have been ill, I have had two ounces of meat, a tablespoonful of brandy, and a pint of tea allowed me daily by the doctor.” (VIN 1/1/24, 5 March 1840)

He had not fully recovered, however, and three weeks later, ten days before his second trial, he explained:

“I am still taking physic, but am daily getting better. An inactive life does not suit my active temperament. I want violent exercise in the open air to keep my body in a proper state. While I was at liberty my activity of public meetings produced continuous and profuse perspirations. All this is stopped here and I ought not to wonder at occasionally feeling poorly. The wonder is that I keep as well as I am.” (VIN 1/1/26, 20 March 1840)

MOOD AND SPIRITS

In spite of his varying health, he was at pains to reassure Minikin that he was in good spirits and that this message should be passed on to his mother, although, of course, it is difficult to determine how much these comments are an accurate statement of his actual feelings rather than putting on a brave face to ease the anxiety of his family and friends.

In his first letter he says: “Be under no anxiety on my account. I am all right and I and my companions are as happy and merry as humans beings can possibly be.” (VIN 1/1/14, 14 May 1839)

While in the next one: “I would and could live here for life rather than leave it dishonourably. Confinement? Pooh!! Trouble? Pshaw!! There are no such things. A free man in mind can never be confined.” (VIN 1/1/15, 21 May 1839)

By February 1840, by which time he had been in custody for nine months and his second trial was fast approaching, his comments were more nuanced:

“Above six months of tedious confinement have passed over my head, and many severe privations I have undergone, and very many have been the petty annoyances to which I have been subject; but you will be pleased to hear that my good spirits and excellent flow of good humour have ever sustained me, and that my moments have flown away upon golden wings. I have methodised my time, and day after day pass through one same dull yet perfectly happy routine of sameness.” (VIN 1/1/21, 15 Feb 1840)

Two weeks later we see a mixture of cheerfulness and foreboding:

“Through my solicitor I have read the most cheering letters to me from all parts, especially from Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Gloucestershire, Somerset and various parts of Wales. You may be sure that if I live once more to be at liberty, I shall rise like the Phoenix from the flames of desolation to the vigours of a renewed existence ... although surrounded by persecution, and with every prospect of having to endure the gloom of a dungeon for many months to come, I am, and shall remain, under every vicissitude of life.” (VIN 1/1/23, 28 Feb 1840)

ATTITUDE TO WOMEN

Of course, being in gaol gives you lots of time to think, and being a virile young man (he was 26/27 years old), one thing that Vincent thought about a lot was sex. This issue has been the subject of an article by Tom Scriven, of Manchester University. (Thomas Scriven, Humour, Satire and Sexuality in the Culture of Early Chartism. Historical Journal Vol 57 no. 1 (2014) p. 157-178.

Anybody familiar with Vincent’s role as a Chartist agitator will be aware that he was particularly popular with women. It is clear from his letters that not only was he popular with them, but that they were popular with him, to the extent that he may have had some difficulty with the modern day #MeTo movement.

In his second letter he comments that he will spend his time reading and studying , “as I have no sweet young lasses here to while away my time with.” (VIN 1/1/15, 21 May 1839)

While later in the same letter we get:

“Give lots of love to all friends and especially to lasses and if when walking through Regents Park (right angle) (i.e. of the sun –PS) you see a young damsel with sweet hazel eyes, intellectual forehead, lips that would turn an anchorite or a stoic and tea totaller to sin, neatly dressed in lavender silk and a white satin bonnet, reading a gilt edge copy of Shelley’s Queen Mab, go up to her, kiss her for me and tender my warmest love. Never mind what Mary Ann (Minikin’s wife –PS) says, tell her you are bound to do an act of such kindness for an imprisoned friend.” (VIN 1/1/15, 21 May 1839)

Tom Scriven points out that London’s parks were favourite haunts for well dressed, attractive prostitutes seeking out wealthy punters. (Scriven p.162/3) Minikin obviously took up the matter in his reply, since in the next letter Vincent continues the discussion:

“A pretty fellow you are to ask ‘what’s the time of day for the right angle’? You ought to have guessed that. Why, the soft and balmy hour of the evening to be sure. When the sun has left us, ‘and the moon doffs her nightcap and squints through the sky’ that’s the time o’day, Master M…” (VIN 1/1/16, 1 June 1839)

Also, in referring to the clothes he has been sent, he says they were “made by the sweet, little, teasing bewitchers! I shall pay them all in kind when I get ‘among them’ again.” (VIN 1/1/16, 1 June 1839)

And in a later letter: “The ladies (in Bath -PS) (bless their hearts) are dieing for me, and, by God, I am dieing for them!!!” (VIN 1/1/23, 28 Feb 1840)

He even had his eyes on the daughter of the High Sheriff:

“I was walking in the yard yesterday, and one of the High Sheriff’s daughters had a peep at me through a window from one of the towers. I did not see her, but she said to the turnkey, ‘Dear little fellow, he looks as well as ever!’ You may judge by this that I am not looking so very bad when this angelic ameranto thinks ‘the dear little fellow’ looks as well as ever!!! Who would not be in a prison to live under the good wishes of these sweet creatures! I think I hear you say, ‘not I’. Poh! Friend! You are a married man! You must say nothing!” (VIN 1/1/25, 17 Mar 1840)

Having studied the whole sequence of Vincent-Minikin letters, including those written before and after his prison sentences, Tom Scriven concluded that the sexual references weren’t just banter between two young men (Minikin was only two years older than Vincent) “purely born from the tedium of Vincent’s largely solitary confinement”, since “long before his arrest … he was boasting about the sexual topography of the nationwide tours he was undertaking.” (Scriven p.158) Rather it was part of Chartism’s public culture, reflected in the publication of erotic poetry by the likes of Byron and Shelley along with smutty stories, scandal and scurrilous satire in some Chartist papers. (Scriven p.169)

This is significant because it undermines the traditional portrayal by historians of Chartism, and of the London Working Men’s Association in particular as being in “the vanguard of Victorian working class respectability” (Scriven p.159) and being associated “with a strict sexual morality going hand in hand with abstinence from drink” (Michael Mason, The Making of Victorian Sexual Attitudes, Oxford 1994 p.124, quoted by Scriven p.160). Rather it is indicative of “a sexually open culture within Chartism” and “suggests a continuum within Chartism of the libertarian, irreverent and sometimes obscene culture of late Georgian and Regency London.”

ATTITUDE TO MAGISTRATES AND LEGAL PROCEEDINGS

Throughout his time in prison Vincent was pre-occupied by the various legal proceedings against him –whether actual or threatened. He saw the hand of the Whig Government of Lord Melbourne (P.M. 1835-1841) behind every move against him, referring to the Whig Ministers as “inhuman devils”, “body snatchers” (VIN 1/1/23, 28 Feb 1840 ) and “base and heartless wretches” (VIN 1/1/25, 17 Mar 1840).

“… the Whigs rightly estimate my value; they know that they have laid their hands on a jewel, and they seem determined to hold it tight. Here I sit, and every time I hear the cell door rattle I fancy I shall receive more indictments!” (VIN 1/1/21, 15 Feb 1840)

He had nothing but contempt for the magistrates that he came up against and for the court proceedings, whether in the Borough Court at Newport or the Monmouth Assizes or the Wiltshire Assizes. This was reflected in his first letter from prison, which gave his view of the hearing at the King’s Head in Newport, where he was brought from London after his arrest in May 1839:

“I cross examined a few of the rascals and elicited enough for my purpose –and to show my contempt for the whole proceedings, when the fool Phillips (the mayor) told me the case was over and that the magistrates would be happy to hear anything I had to say, I smiled and said, ‘Oh! No! I have nothing to say to you -there is nothing in these depositions referring to me! They appeared thunderstruck! Then they retired, returned in about three minutes, and said they had fully considered our case and decided and decided that I should be held to bail to appear at the Assizes myself in £500 and two sureties of £250, and to be of good behaviour to Our Liege Lady the Queen for 12 months. I could not retain myself and laughed heartily when I heard this.” (VIN 1/1/14, 14 May 1839)

The point about the bail terms was that they were ridiculously high –in Vincent’s view illegally high-and that they imposed other conditions that he found it impossible to accept:

“I do not want bail; if I did, I would not look for it, because the magistrates have acted illegally and unconstitutionally. In the amount of my bail, but most especially in the conditions pinned to its tail! Give a promise to Phillips, Brewer and Edwards! Merciful God, preserve me from such a degradation! No! May I become both rotten and mad –May I, after having been a gabbing, slavering half-idiot, for my future life, become, when old, loathsome to the sight of and stinking to the nostrils, if ever I so badly degrade the cause and ruin myself in my own good esteem, as to promise to behave to behave myself to men whose noses I would pull were I not afraid that by pulling them I should poison my fingers!” (VIN 1/1/16, 1 June 1839)

PREPARATIONS FOR HABEAS CORPUS HEARING AND HIS 1st TRIAL

So rather than being released on bail he was taken to Monmouth gaol, where he got busy applying for a writ of habeas corpus which would be heard by a Judge in Chambers in London and, he believed, would secure his release pending trial:

“I shall await with perfect ease, happiness, and good humour the result of the Habeas; it will be time enough to think about bail after that. I have plenty of friends here, and in all parts, who would travel hundreds of miles to bail me, if such was my wish. It is my resolve to stay here, for a time at least.” (VIN 1/1/16, 1 June 1839)

He used his correspondence with Minikin to ask him to line up leading London radicals and Chartists, including Francis Place, Henry Hetherington and John Cleave to give him bail if more realistic terms were offered at the hearing. (VIN 1/1/18, 18 June 1839)

The hearing was successful, the necessary sureties given, and Vincent was released from prison on bail. (Monmouthshire Beacon 29.6.39)

But his troubles were far from over, in the only letter he wrote in his brief period of freedom, written in Cheltenham, he explained that, as well as awaiting trial in Monmouth, he faced the possibility of new charges elsewhere, which led him to go into hiding and put out false messages as to his whereabouts:

“Yesterday I received information by a special messenger from Devizes that the grand jury were about to bring a true bill against Roberts, Potts, Carrier and Vincent for something done or said several months since, the consequence of which is that a Bench warrant is (I believe) now out against me. So I intend to do myself the honour of making myself particularly scarce until the Assizes are over. No catchee, no have. I announced last night that I was going to Glasgow this morning, and from thence to Dublin, and as a matter of course, I am now on the road.” (VIN 1/1/19, 19 July 1839)

While he was fully prepared to abide by his bail terms and present himself for trial at Monmouth, he was determined that the Wiltshire magistrates wouldn’t be able to grab him first. This led him to travel back to Monmouth in a rather bizarre way:

“Heavy bets have been pending on my capture. Fearing that at the 11th hour I should be captured … we left Bristol at 10 o’clock on Monday night in a light cart with plenty of straw, canvass etc etc. We travelled all night and the next day, and I was very safely surrendered here in my old castle on Tuesday (last night) at 8 o’clock ... You would have laughed if you had travelled with us. I will make you laugh should I live to see you again.” (VIN 1/1/20, 31 July 1839)

PREPARATIONS FOR SECOND TRIAL

As pointed out earlier, his first trial at Monmouth was held two days after this letter was written and there is a gap of over six months before the next letter, by which time he was preoccupied with reparations for his second Monmouth trial, while still facing the possibility of a third trial in Wiltshire and the possibility of transfer to another prison or even worse:

“What inhuman devils Whigs are! I know their object. They wished to frighten me into terms. I know that I could avoid the consequences of these trials if I would but nock under, if I would but plead guilty and give heavy bail for my good behaviour, I should soon be free. But I have made up my mind to stand like a man and defy the power of the base faction that now curses our country by its ministry. I suppose I shall soon bid adieu to my present home. Where I shall go to, God only knows. I have no doubt the Whigs would send me out of the country if they could, but I do not think they can manage that; though the Wiltshire indictments are very serious, full of the most base faced perjuries.” (VIN 1/1//21, 15 Feb 1840)

And in his next letter

“… the cloud of persecution has darkened around me. On Thursday last I was waited on by some priggish attorney who served me with copies of two more indictments from the county of Wiltshire and politely informed me that the Assizes commence at Devizes on the 5th of March.” (VIN 1/1/22, Feb 1840)

He also reflects on why he was found guilty in his first trial, blaming his conviction on his defence counsel, JohnRoebuck, the Radical lawyer who had been MP for Bath:

“My last trial was lost because I did not defend myself. Roebuck was not worth a risk ... I know that I should have been acquitted if a good defence had been made. Roebuck’s was a horrible thing, as cold as lead, and formal as the devil; and as distantly repulsive as a thing could be. I know I could have made a far better one, and I trust you will excuse my egotism in so saying.” (VIN 1/1/23, 28 Feb 1840)

Judging by his final letter from Monmouth, he went into his second trial prepared for the worst but putting a brave face on things:

“The enemy is very rabid and is moving heaven and earth against me. Never mind! If I fall again I may live to rise above it all. My spirits are more brisk than ever and this morning I feel better than I ever felt in my life. Now that I am well dressed, all about me say I never looked as well! Do not, I pray you, feel too much on my account. Do not be grieved if you hear I am sentenced to another year or two. I shall be as merry and as happy as ever. From all that I hear, I learn that my prosecutors dread the very thought of my being liberated; they also fear my speech at court.” (VIN 1/1/27, 28 Mar 1840)

And he concludes: “Love to all friends, with a heart beating high to meet our country’s foes and in glorious spirits.” (VIN 1/1/27, 28 March 1840)

TRANSFER TO OAKHAM/RELEASE AND CONCLUSION

Following the second trial and second guilty verdict, Vincent spent a further week in Monmouth prison, but there were no further letters from that place or from Millbank.

The letters from Oakham pick up the story but are beyond the scope of this article, other than to point out that he found Oakham, with its country air “filled with the most delicious odours”, far preferable to the “smoky, stinking miasmas” of Millbank. (VIN 1/1/29, 17 June 1840)

He emerged from prison in 1841, still a convinced Chartist, but now very clearly in the moral force camp and was to become a pillar of respectability and a representative of Victorian values, standing for parliament unsuccessfully on several occasions and embarking on lecture tours which advocated teetotalism, education and self-improvement, leading the Monmouthshire Merlin, which in 1840 had described him as an ‘itinerant demagogue’, nine years later to characterise him as a ‘a patriotic and eloquent man’. (VIN 1/1/40 1.12.1840; Peter Strong, ‘Domestheus Returns: Henry Vincent in Monmouthshire in 1849’, GLH 121 (2017); MM 6 June 1840, 4 May 1849).

Peter Strong

Watch the Henry Vincent Letters video talk now @ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DC9m0xy6q7M