Zephaniah and Joan Williams

A Son and Daughter of Argoed?

LES JAMES outlines for CHARTISM eMAG how hitherto unknown biographical details of Zephaniah Williams and his family in south Wales have emerged during the past two decades. With Sue Allen, he is co-authoring ‘Coal, Beer and Chartism: The World of Zephaniah and Joan Williams (to be published in 2022 by Six Points publishers). They believe that they have a remarkable story to tell.

The Year 2016 was a biographical ‘turning point’ for Zephaniah Williams. His very own handwritten letter, so called a ‘Confession’, was found amongst the Home Office papers at Kew. This discovery not only authenticated the ‘copy letter’ revealed in 1939 amongst Tredegar estate papers, it also authenticated the man.

Thanks to the digital age, Zephaniah Williams no longer has a scanty ‘back story’. We have been able to ‘flesh out’ his kith and kin and map out the ‘progress’ of his life from birth to death. Consequently, both the ‘rogue outlaw’ image projected by nineteenth century officialdom and equally the popular ‘mythical hero’, adopted by the South Wales Miners Federation in the 1930s, can be seen to be stereotypes that fail to do justice to the true complexity of Zephaniah Williams, whom Henry Vincent, described as “one of the most intelligent men it has been my good fortune to meet” (source: Western Vindicator 4th May 1839)

It is also very much our intention to rescue Joan from the neglect of early chroniclers, highlighting her successes. She not only kept their family together and prosperous, throughout the vicissitudes and travails they endured following marriage in August 1819, she also gave unstinting support for Zephaniah in the pursuit of Cyfiawnder (Justice). This was truly so during the ordeal of his trial and the fourteen years of exile that followed. Her decision to join Zephaniah in Tasmania is testament to their shared values, concerning family loyalty and community obligations.

The nineteenth century ruling political elite treated Williams as a non-person. From the summer 1839 onwards, the authorities considered him, their greatest threat and he endured the harshest punishment in Van Diemen’s Land meted out to any of the hundred or so ‘Chartist’ prisoners on the island during the 1840s. At home in south Wales, the powerful feared the emergence of a coalfield folk hero. His origins and early life were deliberately ignored. At the fiftieth anniversary, W.N. Johns (1889), Newport author of The Chartist riots at Newport, November 1839 (74pp) asserted that “Of Zephaniah Williams little is known, and he appears to have been a man who took no prominent part in any public questions.”

If Johns had bothered to explore popular opinion in the Monmouthshire coalfield valleys, he could have garnered a different story. He dismissed Zephaniah’s religious views as blasphemous and totally ignored the social standing and respect he held amongst the ‘Gwerin’ of the Monmouthshire coalfield. When the London Chartist leader, Henry Vincent toured the Sirhowy and Ebbw Valleys in early 1839, Zephaniah was the man he sought to meet.

By the 1930s, bountiful oral anecdotes were avidly consumed by political activists, who imaginatively interpreted Zephaniah’s origins and early life and adopted him as a ‘class warrior’ hero. Aneurin Bevan’s close political confidante, Oliver Jones took on the role of raconteur for local Chartism. Mistakenly, Jones believed that Zephaniah was “the son of a local farmer”. He was much nearer the mark, in his claim that “most of his childhood was spent in and around Gwrhay”, near the district of Argoed. [1] It was certainly one of the several parts of the Monmouthshire coalfield where his father, Thomas Williams, worked the coal seams and Zephaniah followed in his footsteps. Jones was wide of the mark suggesting Zephaniah moved to Coed Duon (Blackwood) during his childhood, for he was aged 25 and married when Thomas acquired a lease of building land in the district.

At the Chartist centenary in 1939, Newport Borough Corporation commissioned David Williams, then a history lecturer at University College, Cardiff, to write John Frost: A Study in Chartism, and identified Zephaniah as “a native of Argoed (Bedwellty) …... forty-four years of age” (p150). Ivor Wilks (South Wales and the Rising of 1839, 1984, p95) perpetuated this myth, overlooking that George Rudẻ had established (1967) [2] from the Australian Convict Records that Zephaniah was born in Merthyr, Glamorganshire. Although he took the ‘Confession’ letter seriously, Ivor Wilks gave no attention to Zephaniah’s early life, beyond what he found in David Williams (1939). Historians lacked the digital data that is now available. For those of us researching today, the twenty-first century online Trove website of the Australian National Library truly lives up to its name.

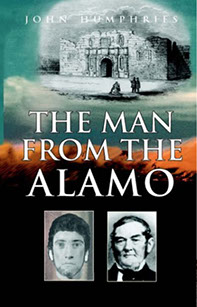

John Humphries (The Man from the Alamo, (2004) p18) was categorical and clear as to the evidence:

In his convict record Williams is stated as being born in 1795, and a native of Merthyr Tydfil. When arrested after the attack on the Westgate he also described himself as a native of Merthyr. Even though no baptismal record can be found to substantiate this, it is more likely to have been Merthyr, or its neighbourhood, than Argoed in Monmouthshire, assumed to be his birthplace largely on the basis of purely anecdotal evidence first published by Oliver Jones in The Early Days of Sirhowy and Tredegar (1969).

The search for Zephaniah Williams’s ‘back story’ started in 2007

Peter Brown, genealogist and Les James at the Chartist Mural promoting meeting at Newport Museum concerned with ‘Chartist Ancestors’ (South Wales Argus, April 2007)

The ‘Chartist Ancestors’ meeting at Newport Museum (April 2007) was attended by some forty people. The event received considerable press and radio interest, thanks to the publicity work of Eoghan Mortell. Kim Colebrook, Ruth Waycott and Ruth Taylor-Davies (HERIAN) raised the profile of Chartism with their Tourism Report and together with Val Williams (Chance Encounters) organised ‘street theatre’ outside the closed down Westgate hotel and children’s activities at Newport Museum.

attended by some forty people. The event received considerable press and radio interest, thanks to the publicity work of Eoghan Mortell. Kim Colebrook, Ruth Waycott and Ruth Taylor-Davies (HERIAN) raised the profile of Chartism with their Tourism Report and together with Val Williams (Chance Encounters) organised ‘street theatre’ outside the closed down Westgate hotel and children’s activities at Newport Museum.

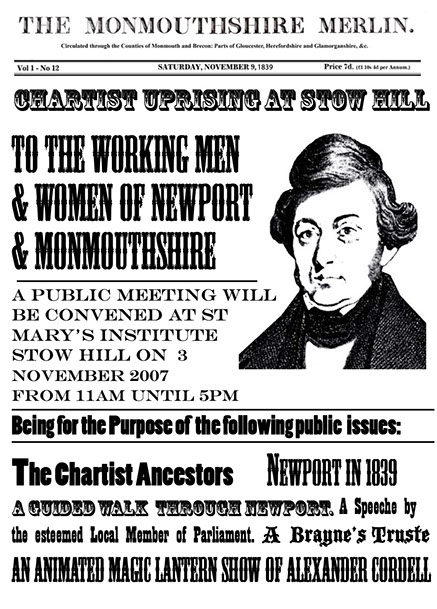

Pat Drewett on behalf of the Accent Newport Trust booked the ‘Stute’, next door to the Westgate Hotel, for a continuation meeting on Saturday 3rd November.

The constituency MP, the late Paul Flynn, agreed to launch the meeting. Paul was one of the staunch band of local enthusiasts, who had been organising Chartist events in Newport since the 1980s. And so, the first ‘Newport Chartist Convention’ was born – a title adopted on the day – for an event that has continued to be held annually at various venues in the Newport district. Last year’s convention was ‘Virtual’ for Pandemic reasons and the 15th Convention (2021) will be at Newport Cathedral (St. Woolos) on November 6th.

POSTER 3 November 2007 (Graphics: David Mayer)

John Wilson, one of the organisers, blogged that “a public gathering such as ours, would have been outlawed as an act of sedition in the days of the Chartists” when a gathering of more than fifty people required permission from the Magistrates.

At this first Convention in 2007, a large part of the afternoon programme was spent hearing speakers reporting their family histories and explaining how they discovered a Chartist amongst their family predecessors. The genealogical digital age was only just dawning, and each contributor had laboured in the archives and libraries of the UK and Ireland.

They shared their researches on local Chartists - John Lovell, William Ferriday and Wright Beatty - and the anti-Chartist Mayor, Thomas Phillips. Others, such as Henry Gwyther of Pembrokeshire and Newport, were mentioned as ‘work in progress’. Terry Frost Jones (New Zealand) was our surprise visitor of the day. Known to have died in Tasmania in 1873, estranged and bereft, nobody expected relatives of William Jones to turn up. But what of Zephaniah Williams?

Nobody stepped forward on the day, although Eifion Lloyd Davies identified a ‘Williams’ descendant living in Blaenau Gwent. Since the first Convention, another person living in the Blackwood district has been mentioned. However, neither proved possible to interview due to their age. It is likely that both were related to Joan Llewelyn, Zephaniah’s wife, rather than Zephaniah, himself.

Nearly fifty years ago, a visitor from New Zealand, visiting family in Newport, told the South Wales Argus in 1972 that her grandmother was a first cousin of Zephaniah. Recent enquiries made by CHARTISM eMAG Family History editor, Sarah Richards, suggest that both parents of one of Mrs. Aileen Hamilton’s grandmothers had the surname, Williams. A common occurrence, in Wales! We are always willing to talk with family members who think they can help our research. Chartist family history continues to be an important aspect of the annual Convention programme.

John Humphries, author of what was then the most recently published book about the Rising joined the ‘Brain’s Trust’ in the last session of that first 2007 Convention.

John Humphries, author of what was then the most recently published book about the Rising joined the ‘Brain’s Trust’ in the last session of that first 2007 Convention.

This session was set up to discuss potential areas for future research/discussion/publication. Despite its title, Humphries book is as much about Zephaniah Williams as it is about John Rees (‘Jack the Fifer’) who had been at the first battle of the Alamo in December 1835, prior to the battle at the Westgate (Newport, south Wales).

Zephaniah had, of course, never been to Texas.

Comparing the lives of these two extraordinary individuals, makes for fascinating reading. Both were ‘wanted’ Chartists, but unlike Zephaniah, Jack avoided arrest, and escaped by returning to America, sentenced to death ‘in absentio’ at the Monmouth trials. Without the advantages of the digital era, Humphries provided the first biographical attempt to investigate Zephaniah’s pre-Chartist ‘back story’. And even though barely half his book is devoted to Zephaniah, Humphries enhanced public knowledge of the man by an immeasurable factor.

David Williams (1939) was the first to scrutinise the circumstances of Frost, Williams and Jones in Van Diemen’s Land. George Rudẻ (1967) outlined Zephaniah’s mining and business exploits in Tasmania. However, the truly ‘ground-breaking’ work concerning Zephaniah’s 34 years spent on the island, was done by John Humphries, who found hitherto unknown documentation and importantly explored in person, the several places, where Zephaniah Williams survived and lived. Undoubtedly Humphries was the first Welsh writer to seek out the punishment ‘isolation cells’ at Port Arthur penitentiary, where Zephaniah had been incarcerated during his early penal years, following one of his two escape attempts. He located the Williams family bible at Frogmore House in Latrobe, northern Tasmania and the Williams family monument which rests on the bank of the river Mersey, in the region where Williams mined coal following his pardon.

And as far as direct Williams genealogical descent in Tasmania is concerned, Humphries provided family historians with closure. His research (p281, ftn69) shows that both the Williams’ grandchildren, died childless - Llewelyn Atkinson, solicitor (1945) and Joan Boadle, neẻ Atkinson (1965). A high proportion of the capital that George Atkinson, Jnr. inherited from Joan and Zephaniah and turned into propertied wealth, ended up benefitting the ‘public good’. It is fitting that the family cemetery monument was moved to Atkinson Park in 1987. Llewelyn served as a member of both Tasmania’s State Parliament and the Australian National Parliament.

Sharing his thoughts at the 2007 Convention about future work to be done, Humphries’ left us three vital suggestions. He persuasively argued that there was more to find out - about Zephaniah, the voyage of the Mandarin to Van Diemen’s Land and what happened at the Westgate. Interestingly, in the years that have followed, all three of these themes have been, and still are being tackled in varying degrees and in new ways by the Newport Chartist Convention.

The ‘ZW Group’ is an informal research group that emerged during the years following the 2012 November Convention at Newport, where I reported in a short paper entitled ‘Letters from the Mandarin’, that Colin Gibson (Gwent Archives) and myself were searching for the original letter that Zephaniah Williams wrote (25th May 1840) to Dr Alexander McKechnie, the Superintendent-Surgeon in charge of the convicts aboard ship. The existence of a copy of this letter at Tredegar House came to public attention in May 1939, when the South Wales Argus running a headline ‘Gwent Move to Make Britain a Republic’, dramatically, but misleadingly, presented the document as a rebel leader’s ‘confession’ of insurrectionary intent.

The Argus story of insurrection sat uncomfortably with the narrative that David Williams had completed and was preparing to send to the publishers that June. In contradiction to nineteenth century texts that presented Frost, Williams and Jones as traitors, he was championing the innocence of three advocates of democratic rights, who had endured an injustice in January 1840, which took sixteen years to correct. David Williams described the letter as a ‘supposed confession’ and avoided argument by treating it as a ploy to ‘curry favour’ with the authorities (p288) – the desperate last move of a man heading to penal servitude in Van Diemen’s Land.

In his opening lines, Zephaniah Williams stated that he had no intention of providing the names of anyone involved. He emphasised that he knew nothing about what was happening in other parts of the country and focused attention on the four-pronged insurrectionary strategy, aimed at Merthyr, Abergavenny, Newport and Cardiff, that had been discussed in the south Wales Chartist lodges. His plea was very direct. John Frost, supported by himself, had rejected this ‘break out’ military action. The rest of his letter describes a range of activities undertaken by the Chartist lodges – such as arming, drilling, planning to take hostages. Williams sought to show that he and Frost had done their best to thwart extremist plans. Little of this was news to the Home Office, who had been supplied with ample details collected by magistrates, local police and the military from informers. A number of ‘state agents’ appear to have been placed aboard the Mandarin, to watch and entrap the three Chartist prisoners.

Importantly, David Williams did not doubt the authenticity of the letter, which he was shown with copies of two other letters written by Frost aboard the convict ship Mandarin. These are listed in his bibliography viz ‘Lord Tredegar’s Library: Copies of three MS letters from Frost and Zephaniah Williams’. It seems too that he had gone to considerable lengths to view these documents. In the Preface of his centenary book (1939) he expressed his indebtedness to Lord Tredegar (i.e., Evan Morgan) ‘for permission to consult three unpublished manuscripts in his possession’. And within the three footnotes for each copy letter - Williams to McKechnie p287, Frost to O’Connor p294 and Frost to Morgan Williams of Merthyr p332 - he states that the document was seen in Lord Tredegar’s Library, ‘kindly placed at my disposal by his Lordship’.

Surprisingly, he was not shown Octavius Morgan’s papers relating to his activities as leading magistrate in the aftermath of the Rising. Since the 1950s, these can be accessed in Box 40 (Tredegar estate) at the National Library of Wales. The three copy letters he saw are included (40/1 & 40/2) in the same box. Their date and purpose of their creation and how they came into the possession of the Morgan family, is unknown, but all three are assumed to have been produced in the same clerical office and no other pre -1939 ‘copies’ are known to exist.

Given that David Williams, twenty years later when writing the chapter about ‘Chartism in Wales’ in Chartist Studies, 1959 (ed. Asa Briggs), remained convinced of the genuineness of these copy letters, Colin Gibson and myself were confident that there was every good reason to hope that the originals survived somewhere amongst the vast body of uncatalogued State papers in the care of the National Archives.

Our hopes soared when searching Colonial Office papers at Kew, I found evidence that Lord John Russell, the Minister, had received (23 Nov 1840) three letters from Hobart. In the margin of the ‘pro forma’ letter reporting arrival of the transportation ship Mandarin (3 July 1840), John Franklin, the Governor of Van Diemen’s Land, listed three letters he was attaching, written by two prisoners aboard ship:

- John Frost to Morgan Williams of Merthyr dated May 4th

- John Frost to Feargus O’Connor dated May 4th

- Zephaniah Williams to Dr McKechnie dated May 25th

Russell instructed his Under Secretary to dispatch them to the Home Office. Colin Gibson identified appropriate series of Home Office Letters kept at Kew and our search began – but to no avail, despite the expert advice of Chris Day, an in-house HO specialist at Kew.

A growing body of people, including Dr Katrina Navickas (Hertfordshire University), joined in the hunt for the original letter, following publication in 2015 of my book Render the Chartists Defenceless, which tells the story of the Mandarin voyage, using the reminiscences that John Frost spoke and wrote about, following his return home in 1856.

One night in April 2016, Sarah Richards settled down to study 595 images recently provided online by ‘FindmyPast’ from a Home Office file devoted to ‘Frost, Williams and Jones’. She had found a treasure trove of documents. Going through the images online, in the middle of the file – Eureka! The original letter was subsequently tracked down at the National Archives. The three ‘lost’ letters, written aboard the Mandarin, are together in the file, as left by home office officials following the issue of pardons to Frost, Williams and Jones between 1854-57.

Finding the ‘Williams-McKechnie’ Letter at the NA, Kew 5th October 2016. (Peter Clark pic)

For Full Discovery Story - see Edition no 10, Autumn 2016 item1. http://thechartists.org/magazine10-eureka.html

Emboldened by this success, the ‘ZW group’ gained momentum. Driven by Sue Allen’s enthusiasm and knowledge of the Sirhowy valley’s history, the group expanded and collaboratively ‘mined’ the available digital sources. Pre-Covd19, archive collections and sites were visited. Maps, Tithe and Land tax records, Newspapers (Welsh and English), Trial documents, Census returns, Births, Marriages and Deaths data were all explored - with startling results.

Sue Allen and David Mills were simultaneously engaged in the research group that Lyn Pask, retired NCB mining engineer, brought together preparing for the 200th anniversary of Blackwood’s foundation in 1820-22. Lyn is the recognised local expert on John Hodder Moggridge, the founder of Blackwood, and he has generously shared his knowledge of the Moggridge estate and coal mining in the district, improving greatly our grasp of the complex social forces that were impacting on the Sirhowy Valley during the first four decades of the nineteenth century.

Argoed is in the Bedwellty parish, so the decision of John Humphries (2004) to search the parish marriage registers for a Merthyr born Thomas Williams made sense. And he found that Thomas Williams of Penderi (north-east of Merthyr Tydfil) married Mary Thomas of Bedwellty at her parish church in 1787. (Humphries 2004, pp59-60) The marriage date conveniently fitted with Zephaniah’s birth year of 1795 and as Thomas died in 1825, leaving a widow named Mary – it seemed that Humphries had found Zephaniah's parents.

However, when Sarah Richards and Sue Allen scrutinised probate and parish records for Thomas and Mary Williams, it became apparent that Zephaniah was not his only child, that Thomas had remarried and both he and Mary had extensive families from previous marriages. Mary Williams was Zephaniah’s stepmother, and her maiden name was not Thomas. Humphries had incorrectly identified Zephaniah’s parents.

The Williams family were very definitely a Merthyr family. Sue Allen, writing in Gelligaer Historical Society Newsletter (December 2020) sums up the ZW Group’s findings about the arrival of Zephaniah in the Argoed district circa 1804 aged 8-9 years, when his father, a recent widower, married Mary George, widow, and heiress to Argoed Genol farm. Mary’s father had been a business associate of Thomas Williams:

“Zephaniah’s father, Thomas Williams, a widower, had moved to Penmain in the parish of Mynyddislwyn after the death of his first wife in 1803. He had been one of four partners in the building of the Rhymney Union Ironworks. In his working life, he had picked up a wide knowledge of minerals and mining and he was interested in the coalmining prospects that were opening up in the area around Argoed.”

The ‘hamlet’ of Penmain was an administrative zone at the northern end of the parish of Mynyddislwyn, which stretches along the eastern side of the river Sirhowy, from above Penderi southwards to the village of Penmaen, where one of the oldest Independent Churches of Monmouthshire was situated.

Joan, born in 1800, grew up at Penderi Farm located above the Sirhowy river, on its east side, where the valley narrows as a cwm. Looking westward, from the fields of Penderi, Joan could see Argoed Genol farm high up on the steep hillside opposite. And down below Argoed Genol, during the first twenty years of Joan’s life, the Sirhowy tramroad came into operation, running along a rocky ledge, into a major industrial thoroughfare. It was here, during the formative years of both Joan and Zephaniah (1800-1820) that houses, and a chapel, were erected alongside the tramroad, creating what became known in the later nineteenth century as Argoed’s High Street.

Looking East towards Penderi farm, from the barn of Argoed Ganol. Cwmcorrwg is in the valley below Penderi (pic: David Mills 2020)

Married in 1819, Joan and Zephaniah were living in 1820, in one of the few houses at Cwmcorrwg, perched at the very edge of the east bank of the Sirhowy, below Penderi Farm. It was here that their first child was born. They later lived at Penmaen, a short distance to the south of Argoed on the east side of the river Sirhowy in the parish of Mynnydislwyn, loyal members of the Argoed Baptist congregation.

The Williams- Atkinson monument at Latrobe, Tasmania

JOAN WILLIAMS

THE BELOVED WIFE OF

ZEPHANIAH WILLIAMS

AND SECOND DAUGHTER OF THE LATE

LLEWELYN Esq

PENYDERI HOUSE, MONMOUTHSHIRE

SOUTH WALES

WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE 22nd Nov 1863

AGED 63 YEARS

Facing eternal exile, Zephaniah claimed the place in Monmouthshire that molded Joan, and himself, and bound them together, a ‘Daughter and a Son of Argoed.’ The monumental inscription, authored by Zephaniah, broadcast Joan’s pedigree, her kith and kinship, and origins.

Although not born in Argoed, Zephaniah was a ‘native’ in the true sense; Penderi Farm was at the centre of their shared ‘hinterland’ - the fields, woodlands and communities of people of the mid Sirhowy valley.

Who’s Who in the ZW Group

Alongside Les James and Sue Allen, leading players are David Mills (Gelligaer Historical Society) and Sarah Richards, Chartism eMAG Family History editor. Sarah lives in the north-east of England, has Welsh antecedents and a Blackwood Chartist (William Davies) in her family.

The Covid pandemic has delayed and changed the events planned at Blackwood. The organiser Lyn Pask keenly supports our publication, which presents the ‘prehistory’ (1800-20) and early history (1820-40) of the ‘Blackwood’ district through the experiences of the extended family of Zephaniah and Joan Williams.

From the Pontllanfraith Local History Society, Gloria Williams contributes her expertise on the Chartist families of Blackwood. Launched in 1820 as a planned model village, Blackwood was not built ‘in a day’. It evolved over decades. One of the first three houses was erected by Thomas Williams, assisted by his son, Zephaniah. Bill Smith (Gelligaer HS) generously shares his extensive knowledge of the Monmouthshire iron industry and its tramroads.

Colin Gibson (Gwent Archives) has provided continuous assistance and guidance. Huw Williams has maintained a constant interest, as to Zephaniah’s connections with Merthyr and Rhymney. We are grateful for the research/editing assistance of Dr David Osmond and Ray Stroud (from Six Points, our publishers in 2022).

Footnotes

[1] First appeared in published form 1969, Oliver Jones ‘Zephaniah Williams: The Man and His Mind’, Presenting Monmouthshire, no 28, pp28-32.

[2] G. Rudé, 'Williams, Zephaniah (1795–1874)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/williams-zephaniah-2795/text3985, published first in hardcopy 1967