'King Crispin' and the Brynmawr Chartists

Eifion Lloyd Davies

“For many years I have been interested in the Chartist uprising and the role that David Lewis, originally from West Wales, played in the story of Brynmawr. But all I knew about him was that he kept a beer house on Boundary Street in Brynmawr named the King Crispin and that he was a cobbler by trade.

Some time ago I was fortunate to be able to borrow some notes that the late Ray Hapgood had done whilst he was looking into David Lewis’s history. Using those brief notes, various reference books and over the years researching the newspapers of the day, I have been able to put together this article. I’m sure there is more still to come to light.”

The district of Brynmawr, sometimes referred to as Waen Helygen, had a militant history of social reform; according to Ness Edwards, the Scotch Cattle had their first meeting in the district near the Cornish Pond on the outskirts of the town in 1832. They were highly active in the Brynmawr and Nant y Glo area, and a ‘scotching’ took place in the town early in 1839 “where Evan Thomas had failed to get permission to introduce a stranger to the art and mystery of mining”. He was severely beaten (4). Throughout the coalfield, many members of the ‘Cattle’ became active card carrying Chartists and during 1839 the militancy of the Brynmawr Lodge most definitely increased. One thing is certain; the men and women of Brynmawr were staunch supporters of the Charter.

It was reported in the Glamorgan Monmouth and Brecon Gazette and Merthyr Guardian on the 25th May 1839, nearly six months before the November Rising, that:

“About a hundred and fifty chartists marched from this neighbourhood (Brynmawr) on Monday last, to Tredegar, to join their comrades in their march to Blackwood, and such motley disreputable assemblage we venture to assert, was never before seen collected together. Their destination was Blackwood and the arranged meeting passed off tranquilly; several thousand had assembled from the neighbourhood and the surrounding towns. Mr Frost, the ex-magistrate, and some two or three other persons harangued the multitude, but all violence was avoided. The business of the day was commenced and concluded with prayer.”

David Lewis was born 1 November 1802 at Llanarth, Cardiganshire; his parents were Thomas Lewis and Mary Ann Jones. He and his wife, possibly named Rachel (?), had three children: Ann, Hannah and John. Both Ann and Hannah were born before the family moved to Brynmawr (2).

They came to Breconshire in the mid-1830s and Lewis, with his wife’s assistance, rapidly established a successful business, employing at least ten cordwainers and keeping a busy beer house in Boundary Street. A cobbler by trade, he called his pub the ‘King Crispin,’ which became his own nickname. Saint Crispin is the patron saint of cordwainers, (the traditional name for shoemakers). A beer house could only sell beer, but did not require a magistrate’s licence, provided it did not sell spirits. By the 1850s there was a staggering 77 places where alcohol could be bought in Brynmawr and nearly 50 of them were beer houses (3).

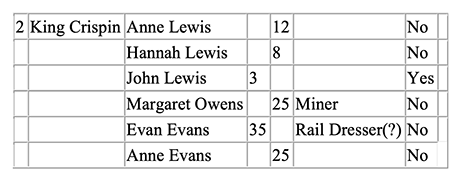

Census Return 1841: King Crispin

David Lewis was absent in Milbank Penitentiary,

His wife was also not present and is not recorded.

Only John, aged 3, was born in Brynmawr.

Lewis sold his goods at local markets and had a ‘standing’ at the Nant y Glô market, ideally situated close to the Bush Inn on Market Row. This market was held on land leased to the Nantyglo ironworks and when the ironmaster Crawshay Bailey, heard about Lewis’s Chartist activities, he had him thrown off the site. Bailey had been informed that the Brynmawr lodge, formed 1838 (1) was holding regular meetings at the King Crispin. Similarly, Crawshay Bailey gave his blessing to a band of ruffians who entered Zephaniah Williams’s public house, the Royal Oak, in neighbouring Blaina and tore a copy of the Chartist National Petition to shreds, by declaring the Royal Oak out of bounds to any of his workers. David Lewis claimed that Crawshay Bailey sacked three workers for being Chartists and for reading Vincent’s newspaper, the Western Vindicator (1)

Not surprisingly, David Lewis became ever more militant and the bonds between the lodges at the King Crispin and the Royal Oak welded.

The boundary between Aberystruth parish (to the south) and the Llangattock and Llanelli Parishes (to the North) is shown on the map by a thick black line that runs below the Heathcock Inn. Boundary street, running north -south, was the divide between the Llangattock (W) and Llanelli (E) parishes. The King Crispin beer house was located on the Llanelli side, at the southern end of Boundary Street..

Photo shows Boundary Street (Looking south) in Brynmawr. The three parishes of Aberystruth, Llanelli and Llangattock meet at the far end, where the road meets Bailey Street. A parish boundary stone marks the spot and above it is a commemorative plaque.

The (demolished ?) King Crispin stood at the far end.

Leader of the Brynmawr Chartists, Lewis was undoubtedly Breconshire’s most committed Chartist propagandist. On his business journeys, he held meetings to try and convert the people to Chartism. With a colleague, he held a meeting in Brecon that the Monmouthshire Merlin (26 October 1839) reported:

“The respectable delegate, who has taken upon himself the mission of coming to enlighten the darkness of the inhabitants of Brecon, is landlord of the King Crispin beer house, Brynmawr near Nantyglo. In his speech, he said that Mr. Frost would, after they had formed a society, come and make a speech for them, and that Mr. O'Connor would also come to them, (i.e., Fergus O’Connor) —he was a nice man, he had plenty of tongue and plenty of money. The delegate (i.e., David Lewis) handed a paper, on which was writing, to the chairman, to be read to the meeting. (It is not mentioned in the report who had chaired the meeting). The chairman, not finding himself competent, desired the "learned" delegate to do so, but this ignorant inciter of rebellion (for reasons which we dare say he can very well account) also declined. (David Lewis could read and write a little, see below the report from the court case). Some six or seven other gentlemen found themselves in the same predicament; but at last a person was found (one of the spectators) who read it. It comprised several resolutions one of which was, that a society should be formed, and each member to pay a penny per week that the society should use all moral force to obtain the Charter. Several of the gentlemen made anxious inquiries about the word "moral" and said that all property ought and should be equally divided that no counter-hopper or clerk should become a member. The persons who have assisted in getting up such a meeting here are entire strangers. After much coughing, the meeting was addressed by a son of Crispin, who moved that all persons who would not join the society should leave the room; upon which three-fourths rose up and left.” (When the reporter refers to “son of Crispin” he was not referring to David Lewis’s son but to a member of the King Crispin lodge).

There may have been another reason for their visit to Brecon in late October – this is only days before the march on Newport, when attempts were being made by Chartist activists in Monmouthshire to persuade soldiers to desert their regiments. Earlier that month, David Lewis was also present at a meeting held at the Royal Oak in Nant y Glo in early October 1839 presided over by John Frost of Newport and a leading member of the National Convention, campaigning for the People’s Charter. Frost urged the meeting to be vigilant, claiming he was:

“pleased to find the further he came from home, the more peaceable the country appeared; and exhorted them as they valued the success of their common cause, not to commit themselves by any premature outbreak”.

He also said that

“the men of the Welsh hills were properly organised, and ready at any time to meet him when called upon”.

The Glamorgan Monmouth and Brecon Gazette and Merthyr Guardian dated 19th October 1839 ended their report thus:

“After Mr Frost had done speaking the notorious landlord of the King Crispin beer-house, Brynmawr, acted the usual part assigned him at such meetings, by getting upon the dung-bill and proposing three cheers for the charter, &c., &c., &c., which occupied a quarter of an hour, after which the meeting quietly dispersed. Another meeting of a private nature was held the same evening at the above beer shop, and did not break up till two in the morning, when the hooting and yelling along the roads, caused so much terror in the minds of some of the inhabitants, that they left their beds and kept on the watch till day-break.”

According to Ivor Wilkes, this was a private meeting at the King Crispin of the rebel leaders and John Frost also attended (4).

David Lewis was highly thought of by Henry Vincent - a prominent leading Chartist and a great orator - who said of him:

“He is a famous fellow .... There is no mistake about him. He says what he means and he works hard to spread our principles” (1).

In the same vein, William Edwards, another prominent Chartist described David Lewis and Zephaniah Williams as “two of the best Chartists I ever met.” (4). Consequently, David Lewis rose in the ranks of the Chartist movement attending the coalfield meetings that led up to November Rising (4).

The meetings at the King Crispin Lodge were held twice a week, normally on a Monday and Wednesday evening. These meetings were so well attended that additional rooms were made available. When Henry Vincent was touring the Monmouthshire valleys during early 1839, he came to Brynmawr and visited the King Crispin. That Tuesday evening April 23rd, men and women packed the Royal Oak at Blaina, kept by Zephaniah Williams, to hear such a famous speaker, who was staying the night there. A massive crowd spread down the hillside behind the pub, addressed by Vincent who defiantly faced Ty Mawr, the home of Crawshay Bailey, situated on the opposite side of the valley.

David Lewis attended the Chartist meeting at the Coach and Horses in Blackwood on the Friday before the fateful march on Newport. It was at this meeting that the final plans of the march were made for the Gwent men. News of the meeting spread up the valleys and at Brynmawr new and old Chartists met upstairs in the King Crispin. David Lewis reminded them that they must not lose this fight. If they had to kill anyone it should be the army officers and those in authority (1). This would be brought up at his subsequent trial at Brecon. David Lewis also told new recruits that if the people lost, they would be slaves and if they won, they would be comfortable.

Saturday 2 November was a busy day upstairs at the King Crispin as new and old Chartist gathered to swear an oath of secrecy on the Bible. Chairman of the lodge, Ishmael Evans was backing Lewis’s militant stand, confident that the Welsh and English Chartists would rise on the following day.

That Sunday, supporters gathered at the homes of Ishmael Evans and David Lewis and some men collected weapons and ammunition from the house of James Godwin (1). As confirmed by Williams’ letter written six months later aboard the Mandarin, there was a change of orders for all the lodges at the northern edge of the coalfield. Originally Lewis and Evans had been assigned to filter their men into Abergavenny in preparation for taking over the town (4). Many Brynmawr men had gone to the town already, not all with the intension of attacking the place. Some had gone to escape being press ganged into the march on Newport. As a result of the Friday meeting at the Coach and Horses, nobody was required to march on Abergavenny, instead all were expected to head south and join forces with Frost in the Rogerstone district.

As to this march on Newport, David Lewis warned that the men would return “up to their shoes in blood”. He clearly believed that abandoning the planned ‘break out’ from the coalfield, heading simultaneously for Brecon, Abergavenny, Newport and Cardiff, was a disaster. His unwillingness to move, enraged Zephaniah Williams who was waiting in the rain on Mynydd Carn y Cefn for the men of Beaufort, Nant y Glo and Ebbw Vale, as well as Brynmawr to gather. He disassociated himself from David Lewis (1). Williams was siding with cautious Frost. David Lewis and Ishmael Evans did not take part in the march on Newport; they waited to see the outcome at Newport.

And those who did eventually return, told tales of woe. At least twenty Chartists were killed and many more maimed by the firing by the 45th Regiment at the Westgate inn. Amongst the dead, there were two men from Brynmawr – David Davies, and his son David. They are commemorated with a plaque.

Before most had got home, on Tuesday the 5th of November a posse of constables and soldiers arrived at the King Crispin from Brecon and found David Lewis hiding in a shoe chest. Ishmael Evans and others were rounded up, as were the papers and a flag belonging to the Waenhelygen (Brynmawr) Association. All were taken by a detachment of the 12th Regiment. These documents are not known to have survived. Both Ishmael and David were residents of Breconshire. Sixteen Chartists, excluded from the lists of the Special Commission to be held at Monmouth, were committed to trial in Breconshire at the Lenten Assizes in the Spring of 1840 (4).

Ishmael Evans, 51 labourer, was charged that he on the second day of November, 1839 as chairman of a certain society, called a Lodge of Chartists, held at the house of one David Lewis, in the parish of Llanelly did unlawfully administer certain unlawful oaths, with purpose of binding Charles Lloyd and Owen Williams, to become members of the said Lodge of Chartists, and for inciting the members of the said society to arm themselves to resist the laws of this realm

David Lewis, 37. shoemaker, was charged on the oaths of Charles Lloyd and Owen Williams, for that he, on the 2nd day of November, 1839, did aid and assist one Ishmael Evans, as chairman of a certain society, called a lodge of Chartists, held at the house of the said David Lewis in the parish of Llanelly, in unlawfully administrating certain unlawful oaths, for the purpose of binding the said Charles Lloyd and Owen Williams, to become members of the said lodge of Chartists, and for inciting the members of the said society to arm themselves to resist the laws of this realm.

Mr. John Evans Q.C. appeared for the prosecution, opened the case, and said the duty of addressing the jury in this case had devolved upon him; this case had arisen from proceedings connected with the memorable insurrection of November last, and the prisoners indicted under the statute of 37 George III, enacted against the administrations of unlawful oaths.

The prosecution had thus adopted a very lenient course. Had the full facts of all the defendants’ possible offences been laid before the jury, it would have been evident that the prisoners had been guilty of offences of a much more serious nature than taking unlawful oaths and though the present indictment did not involve any charge which could endanger their lives, yet it would subject them to transportation for seven years.

The first to give evidence at the Brecon trial, answering prosecution counsel, was Mr E. L. Richards: - ……... is a rail cutter; lives at Cwm y Crachen remembers the night of Sunday of the Chartist riots he was coming from a public house at Brynmawr; he was stopped by Kidley (This was Thomas Kidley member of the King Crispin Lodge.) (4) know him by the name of George; Evan Davies and another man were with witness; Kidley had a pickaxe handle; be said, "You must come with us;" while witness was speaking to Kidley, his companions ran off; cannot tell if it was in the parish of Llanelly; saw many men coming out of Godwin's house with spears and other weapons; saw David Evans and Daniel Thomas with them; David Evans had a spear; Godwin (James Godwin member of King Crispin Lodge). came out with them; he had something under his frock; Daniel Thomas had a gun heard Godwin say, "I am going to David Lewis, -you go to Ishmael Evans's;" Lewis is the man called "King Crispin he said, "make haste and meet at Zephaniah Williams’, or else we shall not be at Newport before day light;" they went to search several houses; David Evans and Kidley and the other men took witness with them. David Evans said to a man in one house he must come; "he must join this day whether willing or not;" David Evans told Thomas to shoot anyone who would run away Daniel Thomas said, “Yes, by G-d!" witness was much frightened; knows the King Crispin beer house; does not know if there is a Chartist lodge there; there was at that time; heard people say one Beddoe was chairman heard of a lodge at Zephaniah Williams’.

SENTENCES OF THE CHARTIST PRISONERS.

(From The Cambrian 4th April 1840).

“The eight prisoners tried yesterday, were now placed at the bar, and his Lordship, addressing Ishmael Evans and David Lewis, said: -

“You, Ishmael Evans and David Lewis have been convicted on the most satisfactory evidence, the one of the offence of administering an unlawful oath to Charles Lloyd and Owen Williams, and the other of aiding and abetting in the same. This is the form which the present charge has taken, and you ought to be extremely grateful for the lenity which those who have had the management of the prosecution have shown in adopting that mode of proceeding; for it appears quite clear from the evidence, that you might have been prosecuted for the highest crime known to the law. The utmost punishment to which you are liable under the charge on which you have been convicted is very slight indeed when compared with the enormity of the crimes which you have committed and which it is difficult for me to find terms sufficiently strong to describe. You were leaders of a body of misguided wretches in a most treasonable conspiracy, and induced many of them to join in a design of the most criminal nature, and involving the most extensive schemes of mischief which have been conceived in this county, I am happy to say, for many years. It is quite clear that the oath which you administered was an oath of secrecy, admitting these men into the body of Chartists. It is also plain that on the same night you initiated a great number of persons into a combination of no common kind, and the wicked speeches which you addressed to the infatuated people whom you had succeeded in collecting together fully explain a barefaced treason and wholesale murder. You desired them to provide arms and offered to furnish them with arms yourselves; you exhorted them to be ready to take Newport and we find by the evidence in other cases they did assemble, many of them with loaded guns, which their firing proved to have been loaded. And what were they to do with these guns? Why you told them they were to shoot the officers, and the sergeants, and the rulers; that is to murder them. That was not only your design, but, in fact, you swore them in to commit murder; for in case you had succeeded to your full intention of taking Newport, no one on reflection can doubt but that the murder of many innocent men, women, and children, would have been the inevitable result. You also told them to murder the officers and the great men and what did this mean? Why that all who by their own industry, or that of their predecessors were in possession of property the produce of that industry, were to be killed and plundered that was the design of those who called themselves Chartists. It is well-known that many persons in this country hold opinions that great improvements or alterations may safely be made in the representation; but it is remarkable that in your addresses we find nothing at all on these subjects, they breathe nothing but murder and bloodshed. You ought to consider yourselves abettors of the deaths of those persons who have so miserably lost their lives on this unhappy occasion, for I cannot conceive anything more atrocious than your advice to the deluded wretches more ignorant than yourselves. I do not know what share of the blame of your conduct may be attributed to that, as I find by the calendar, that one of you can read but imperfectly, and the other not at all. Indeed this must be matter of great regret for the degree of ignorance which could induce you to give, or others to take, such advice, must be very gross. The infatuation must be deplorable which could lead you to imagine that the troops led by officers, as skilful as they were brave, could be beaten in the manner you seem to have anticipated! Was it possible that you could suppose even if you had succeeded to the full extent of your wishes that the lovers of, freedom and the friends of order would not have rallied around the institutions of the country? Could you suppose tor one moment that your mischievous plans could have resulted in anything but terrible and general destruction, or your own severe and exemplary punishment, if the humanity of the authorities would not protect you from the just consequences of your own atrocity.

The compassionate and earnest desire of the government to let off all the infatuated wretches who embarked in these proceedings with the lightest possible punishment, has induced them to try the experiment of sparing the lives of the chief leaders of the conspiracy: and I for one rejoice that that experiment has been tried, and I hope that no future tumult of the kind will render it necessary to recur to more extreme punishments. It appears that you Lewis told those men that if you failed it would be a matter of transportation only, but, in this you were mistaken, and by this you have furnished those who are opposed to the entire abolition of the punishment of death with the argument that unless you were convinced that the expectation of their own lives being sacrificed would have deterred your deluded followers, you would not have made use of such expressions. But I feel certain that if such occurrences do again take place, it will be imperatively necessary to let the rigour of the law take its course for the actual preservation of society. I hope that if there are any persons present who feel any inclination to join in scenes of the kind, they will seriously consider what I have said; for they must be very ignorant indeed it they fancy that such lawless and treasonable under- takings can result in anything but bloodshed and destruction. I have no view in addressing to you any lengthened observations, but the object of endeavouring to impress upon the minds of all such, either present or not, that it is connected with their interest as well as duty to refrain from any temptation to join in any such designs, as they have now been exposed in all their naked deformity of treason and murder, divested of the least show of liberty or reason, and plainly contrary to the law of God and man. You must now be convinced that if you had been charged with the heaviest crimes of which you have been guilty, you might have lost your lives; and as seven years transportation the extreme punishment affixed by law for the offence of which you have been committed, is in your case a light punishment and a great mercy, I shall, therefore, sentence you to that term”. Sentence of seven years' transportation was then passed in the usual form. "

The Glamorgan Monmouth and Brecon Gazette (25 April 1840) reported that the three Chartists, David Lewis, Ishmael Evans, and John Jones, sentenced to transportation at our last assizes, were removed to Woolwich under the care of the Governor to be put on board the Justitia Convict Hulk, at the Royal Arsenal. The defendants were fortunate not to have been charged high treason, or conspiracy. They were tried for administering illegal oaths only. This influenced how their punishments were subsequently administered

It has not been possible to find out why David Lewis was not transported, but he did prove useful, teaching some prisoners to make shoes during his stay at Milbank and long before he served his three years sentence, he was released on grounds of ill health in 1841 (4). Nothing is known about him after his release, but it has been suggested that when he died, he was buried in Zion Chapel’s burial ground in Brynmawr though this cannot be proved as the burial records are missing (2).

Ishmael Evans who obviously played a particularly important part with the Brynmawr Chartists was transported for 7 years. It is also possible that along with the others the sentence was changed, and he was sent to Millbank, though no proof of this has been found.

Thomas Kidley, 24, labourer, charged, on the oath of William Williams, with being a member of an unlawful combination, and that he on the night of the 3d day of November 1839, with threats, and with divers armed men, compelled the said Wm. Williams, to join such unlawful combination (5). Sentenced to two years hard labour, bound over for 2 years plus £50 (4).

James Godwin, 41, mason, was charged, on the oaths of Rosser Thomas and others, for that he, the said James Godwin, on the 3rd November, 1839, was a member of an unlawful combination and conspiracy, in the parish of Llanelly, and being then and there armed, did incite counsel and advise Wm. Williams, Thomas Kidley, and divers other persons unknown, to assemble together, for an unlawful purpose, and for a breach of the peace. (5) Sentenced to two years hard labour, bound over for 2 years plus £50. (4)

David Evans, 31, roller, was charged, on the oath of William Williams, for that he together with one James Godwin, David Thomas, Thomas Kidley, and divers other persons unknown, being members of an unlawful combination and conspiracy for seditious purposes, on the night of Sunday, the 3rd of November, 1839, in the Parish of Llanelly, with a gun, spears, and other offensive weapons, and with threats, putting the said William Williams in bodily fear, and compelling him and other persons unknown, to join the said combination and conspiracy. Sentenced to two years hard labour and bound over for 2 years plus £50 (4).

Footnotes

[1] David Jones, 1985, The Last Rising.

[2] From the notes of Ray Hapgood and Roger Morgan

[3] The Public Houses and Inns of Brynmawr in 1859.

www.brynmawrhistoricalsociety.org.uk

[4] Ivor Wilks, 1984, South Wales and the Rising of 1839. [5] The Monmouth and Brecon Gazette 28 March 1840

Also, other newspapers mentioned throughout the article.

This article is ‘work in progress’.

The Author welcomes additional information or corrections, all gratefully received via the Editor CHARTISM eMAG

© Eifion Lloyd Davies; August 2021

Eifion Lloyd Davies is originally from North Wales but moved to Brynmawr in the early seventies. He was the President of the Nant y Glô and Blaina Charter Group; he is currently Secretary of the Brynmawr Historical Society and Chairman of the Blaenau Gwent Heritage Forum.

He also runs the Brynmawr Historical Society website.