THE NEWPORT SUFFRAGETTES

THE NEWPORT SUFFRAGETTES

An illustrated talk by Ryland Wallace

An organised women’s suffrage movement operated continuously in Britain for more than sixty years – until the achievement of equal voting rights with men in 1928. It thus dates from the mid-1860s when the issue of the vote emerged as part of a broad-ranging and disparate women’s movement driven by middle-class groups.

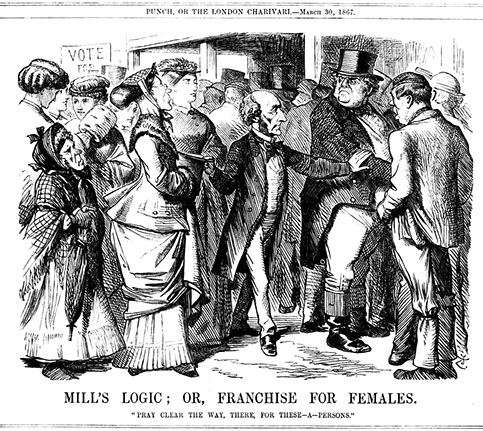

John Stuart Mill cartoon

The campaigners found a male champion in the political philosopher and, at the time Member of Parliament, John Stuart Mill, who submitted the first substantial women’s suffrage petition to the House of Commons in 1866 and then the following year – when the government was in the process of granting the vote to a million more men – proposed the substitution of the word ‘person’ instead of ‘man’ in the new legislation – hence this satirical cartoon: ‘Pray clear the way, there, for these – a – persons’. Mill’s amendment was inevitably defeated – amidst much ridicule from politicians and in the press – but did gain a respectable 73 votes.

At the same time regional women’s suffrage societies sprang up in a number of Britain’s major cities. Albeit intermittently, Newport and other towns in south Wales were drawn into the agitation from its early stages, much of the activity being instigated by the regional centre at Bristol – as in Chartist days, throughout the women’s suffrage movement there were close links across the Severn Estuary.

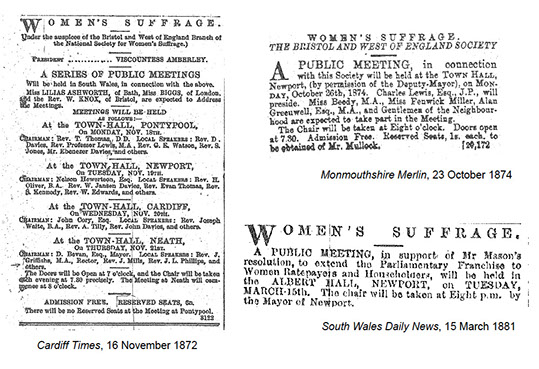

Newport meetings in the Victorian era

Here we have various meetings in Newport in the 1870s and 1880s. Most were under the auspices of the Bristol and West of England Society for Women’s Suffrage and were often part of lecture tours undertaken by speakers from that organisation. The one here in November 1872 was the first women’s suffrage meeting to be held in Newport.

For the remainder of the Victorian era the women’s suffrage campaign was a steady but generally low-key one. In terms of pressure, there was a heavy reliance on petitions, letters to MPs, co-operation with parliamentary supporters and private member bills. Much was achieved in winning public and parliamentary sympathy – nevertheless after four decades of campaigning, legislation actually granting women the right to vote seemed as remote as ever. It was the deep sense of frustration with this situation that led to the formation of a new suffrage organisation in the early years of the 20th century – adopting very different methods of campaigning.

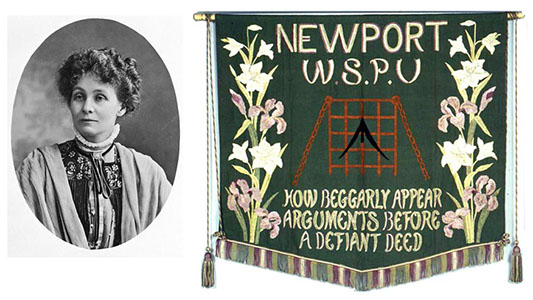

Emmeline Pankhurst

The Women’s Social and Political Union – the WSPU – was founded by Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst, the widow of a radical barrister, at a small gathering of fellow women members of the Independent Labour Party – the ILP – at her Manchester home in October 1903. In aim, the WSPU was no different from the many other women's suffrage organisations that existed before and after this date − 'to secure for women the parliamentary vote as it is or may be granted to men'. At this time, roughly two-thirds of adult men had the right to vote – and, of course, no women whosoever. What distinguished the WSPU was its style and methods, epitomised in its motto – 'Deeds Not Words' – echoed here on this splendid Newport banner in the phrase: ‘How Beggarly Appear Arguments Before a Defiant Deed’.

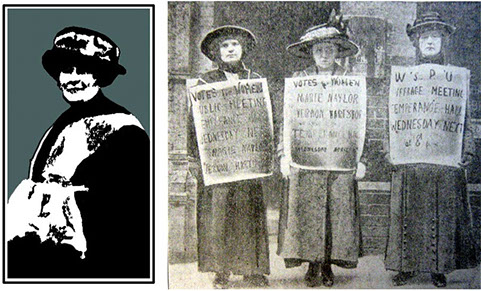

Margaret Mackworth

Newport and Wales’s most famous activist, Margaret Mackworth, the future Lady Rhondda, explained the radical departure thus:

‘Put in a nutshell, the policy of the new militant organisation differed from that of the older body, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), in that instead of asking gently for help, accepting the crumbs offered . . . . it demanded a Government measure, and made it clear from the start that it intended to bring what pressure might be necessary to bear upon the Government to accede to its demand’.

Members of the WSPU were labelled ‘suffragettes’, to distinguish the new breed of campaigner from the suffragists, who had been campaigning for almost half a century. In the decade before the First World War the increasing militancy of the WSPU awakened public consciousness, generated enormous publicity and made ‘votes for women’ for the first time a central issue in British politics. At the same time, it must be emphasised that the suffragettes were very much a minority among campaigners; the vast majority were suffragists – members of the law-abiding, non-militant NUWSS.

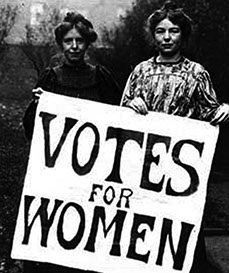

Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenny

For two years after its formation the WSPU remained a rather obscure body on the fringes of northern Labour politics, whereupon in October 1905 it burst into the national spotlight with the arrest and imprisonment of two of its leading figures. Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline’s eldest daughter, and Annie Kenney, a mill worker from Oldham, interrupted a major Liberal Party meeting in Manchester with persistent questions on votes for women. Ejected from the building, they were subsequently charged with disorderly behaviour and obstruction and, in Christabel's case, assault – she spat at the policeman who was arresting her. Refusing to pay the fines imposed, they were sent to prison and – precisely as planned – gained publicity and notoriety. These were the first two suffragette imprisonments – more than 1,000 were to follow over the next decade.

Adela Pankhurst

During 1906-7 the suffragettes would certainly have entered the consciousness of many Newport people. Both Mrs Pankhurst and her daughter, Adela, spoke in the town. Here is the latter explaining and justifying the WSPU campaign in a lecture entitled the ‘Strike of the Sex’ in March 1907. The event was chaired by Mary Keating Hill from Cardiff, who had become the first suffragette from Wales to go to prison for the cause a few months earlier. Suffragette disorder and arrests in London – including the imprisonment of five women from south-east Wales – was also widely covered in the local press at this time.

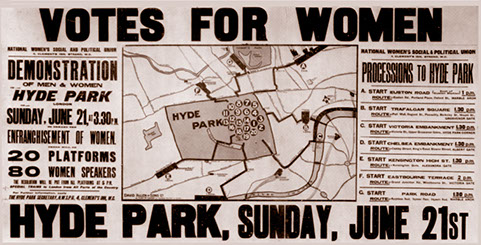

Women’s Sunday, Hyde Park, 21 June 1908

It was this mass demonstration – the first major demonstration staged by the WSPU – which first ignited suffragette activity in Newport – so-called ‘Women’s Sunday’ in Hyde Park on 21 June 1908. In the weeks beforehand, organisers were despatched to various parts of the country in order to rouse support for the event. Two came to Newport and held 10 open-air meetings in 4 days – in public parks, at the docks and at suitable pitches in the town centre – and succeeded in establishing a women’s committee to push tickets and order a banner, paid for by a local collection.

The event itself was a glorious success. Special trains brought suffragettes to the capital from all over Britain – the one from Cardiff apparently conveying 365 women from south Wales. Seven huge processions with groups carrying over 700 banners – those of Cardiff and Newport figuring prominently here – converged on Hyde Park from different directions, where 80 speakers addressed the massive crowd of a quarter of a million people from 20 platforms. Hugely enthused by the whole event, the Western Mail spoke of 'a demonstration unparalleled in the history of British politics', its reporter accompanying the 'Welsh section' describing it as ‘infinitely the most impressive event, the most inspiring spectacle of which I have been a spectator’. Similar processions and demonstrations took place in succeeding years, with a Newport contingent invariably in attendance.

It wasn’t until the summer of 1909 – over a year after this Hyde Park demonstration – that a branch of the WSPU was established in Newport. Again, much of the impetus came from outside the area. Annie Kenney had been appointed organiser for the West of England and from mid-1909 she and her lieutenants turned their attention towards Cardiff and Newport.

Sybil, Margaret, Charlotte and Evelyn

Within a matter of months the Newport branch boasted a hundred members. Its leading figures were Sybil Thomas (above left) and her daughter Margaret, wife and only child respectively of D.A. Thomas of Llanwern Park – one of the great coal magnates of south Wales and a Liberal MP. Sybil had been an active suffrage campaigner since the late 1880s; Margaret appears to have ‘discovered’ the movement shortly before her marriage to a local squire, Captain Humphrey Mackworth, in 1908, at the age of 25. A third member of the family – Charlotte Haig – Sybil’s sister and Margaret’s aunt (‘Aunt Lotty’), who lived in a cottage on the Llanwern estate – was also a staunch local activist.

Subscription lists show that about half of Newport WSPU members were unmarried. According to Margaret, members included ‘young women from every kind of home’ but clearly the majority were solidly middle class, women who tended to have few domestic responsibilities and the time and money to commit themselves to the campaign. Teachers evidently formed a significant element. Mothers and daughters were often active – like, Evelyn Lawton here, and her mother – the daughter and wife of a tailor in Commercial Street. There were male sympathisers too and a men’s organisation was formed in the town in 1913.

Time and Tide, 6 February 1914

The Newport WSPU branch had a continuous and vigorous existence for five years, until the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. Margaret, its secretary throughout the period, recalled the local campaign thus:

‘We formed a branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union, we ran a shop where one could buy suffrage literature, sold our weekly paper in the streets on market days, marched in poster parades, carried out door-to-door canvassing, wrote articles and letters for the local papers, and, above all, held meetings, meetings of all shapes and sizes, meetings in the shop, meetings in little halls, drawing room meetings, street corner meetings (hundreds of street corner meetings) and occasionally meetings in the large Town Hall for Mrs Pankhurst. What people remember now seems to be chiefly the actual breaking of the law . . . It did get broken, of course, but not, after all, so very often. I can remember only four or five people going to prison from our local branch in all the time we worked together’.

‘A great deal of our work which wasn’t law breaking at all was apt to be classed as militant’, she added. And indeed, this was so because many of the activities listed here were new and went against the conventions of the time as regards women’s behaviour. The highly demonstrative, bold, defiant, public nature of the suffragette campaign – the taking of ‘votes for women’ to the streets – was an enormous contrast to earlier activity.

Heckling – Abergavenny Chronicle,

24 January 1908

A new tactic widely employed by the suffragettes was the forceful questioning of politicians at every opportunity. Here are the observations of one Abergavenny speaker in 1908:

‘This question [of votes for women] has recently been brought prominently before the public by the acts of the suffragettes. The public generally has been shocked by the methods adopted by certain ladies to advertise the matter. Serious politicians have been interrupted by women in a manner that mere man would have hesitated to adopt . . . the responsible politician finds his meeting is broken up by insistent suffragettes, who pop up here and there in the audience and disturb his flow of eloquence by unexpected interruptions. That these ladies are willing to incur the wrath of audiences and suffer ignominious ejectment is a new and startling fact in itself . . . there can be no doubt that these extraordinary tactics have resulted in compelling public attention to the question.’

Cabinet Ministers / Reginald McKenna

In Margaret Mackworth’s words, militancy involved ‘reminding Cabinet ministers of what was expected of them’ – something she herself put into action by jumping upon the running-board of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s motorcar while he was electioneering in Scotland in December 1910.

A principal ministerial target was Reginald McKenna, (above) Liberal MP for the North Monmouthshire and Home Secretary from 1911, a post which placed him at the very heart of government policy towards militant suffragettes. This role, exacerbated by his firm opposition to votes for women, made him a detested figure to suffragettes. Here are a couple of local examples of his being hounded by activists:

• His speech in Blaenafon in February 1909 was persistently interrupted by a group of suffragettes who had travelled there expressly for that purpose.

At least one of them was from Newport. She was Elsie Cross Thomas, a 24 year old builder’s daughter, who like the others was ejected from the meeting and then subjected to considerable hostility – which was so often the fate of women’s suffrage campaigners

.

.

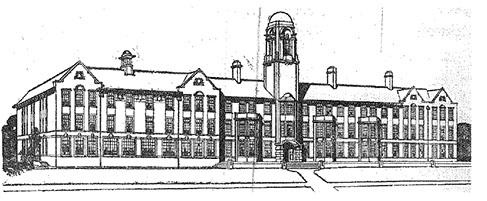

My second example is from July 1912 when McKenna was guest of honour to lay the foundation stone for the new Monmouthshire Training College at Caerleon. Midway through the ceremony, a suffragette rushed forward onto the platform to berate him. She had apparently been ‘sent down from London’ – though she was certainly acting with Margaret Mackworth’s collusion.

Caerleon College

Church services

Suffragettes sought to awaken public consciousness in other novel ways too – such as suddenly making a speech in a crowded restaurant or during a theatre interval. Suffragettes also interrupted church services – attending in small groups and at an appropriate moment bursting into their own prayer. Here is a typical intervention.:

'Oh, God, we Beseech Thee, save Thy Servant, Emmeline Pankhurst, and all who are persecuted for conscience sake. Open the eyes of Thy Church, that it may protest against this torture in prison.’

Window smashing, November 1911

Above all, of course, the suffragettes are associated with law breaking, arrests, imprisonments and hunger strikes. For most of the years 1910 and 1911 there was optimism across the women’s suffrage movement that the deliberations of an all-party parliamentary committee would favourably resolve the issue through what was known as a conciliation bill. The Liberal Government’s sudden rejection of this in November 1911, in favour of a manhood suffrage bill, left campaigners shocked and angered. The WSPU now abandoned its eighteen-month suspension of militancy and entered into a period of widespread attacks on property, which continued unabated until the outbreak of war in August 1914. Suffragettes were adamant that ‘broken windows’ were caused by ‘broken Cabinet promises’.

In Wales itself, there were just two incidents of window smashing by suffragettes as a form of protest – neither in Newport. One was the ‘Visit of a Window Warrior’ to Abergavenny Post Office and the other two suffragettes attacking shops in north Wales, in Cricieth.

Women from Newport were however involved in the various mass window-breaking outbursts in central London. This is November 1911 – when clashes with police in Parliament Square was followed by window smashing at government offices and business premises. The 223 arrests included two women who were reportedly from Newport. One was Bessie Davies, who was convicted of trying to break through a police cordon and striking a constable; she was fined 7 shillings or 7 days imprisonment, choosing the latter. The other, Charlotte Rice, was convicted of trying to break through the same police cordon and fined 5s or 5 days imprisonment, choosing the latter. Mrs Davies was evidently a Newport WSPU member but Miss Rice is something of a mystery with Margaret Mackworth telling the press that the local branch had no knowledge of her whatsoever.

Window Smashing, March 1912

‘The argument of the broken pane of glass is the most valuable argument in modern politics’, pronounced Mrs Pankhurst. These were the headlines after further offensives over several days in early March 1912. Among the 217 arrests was Olive Fontaine, a prominent Newport WSPU activist. Twenty years old and the daughter of an iron founder, she served a month with hard labour for smashing a police-station window, before returning home to a heroine’s welcome. ‘Back From Holloway – Newport Suffragette Welcomed Home’. ‘. . . she was glad to be out of Holloway, but gladder still that she went’.

Telegraph and telephone wires

The spring and early summer of 1913 saw a wave of telegraph and telephone wire cutting in the Newport-Cwmbran area, the perpetrators leaving behind various papers relating to the votes for women campaign. ‘We won’t be quiet until Mrs Pankhurst is out of prison’, read a typical note attached to one telegraph pole.

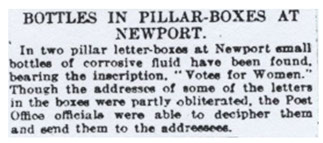

Letter boxes

There were plenty of letter-box attacks across south Wales in 1912 and 1913. One in particular – this one – generated a great deal of publicity at the time and is fairly well known locally today. In June 1913, Margaret Mackworth – with, as she later wrote, her ‘heart beating like a steam engine’ and her ‘throat dry’ – deposited chemicals in this box outside the cemetery in Risca Road. Arrested and convicted, she refused to pay the £10 fine imposed and was sentenced to a month’s imprisonment in Usk Gaol, where she promptly went on hunger strike. She was released after five days under the terms of what was known as the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ – which allowed hunger strikers to be temporarily released on license until fit to resume their sentences, at which time they could be re-arrested. While on release, Margaret’s fine was paid anonymously.

This press cutting shows that there had been attacks on letter boxes in Newport before Margaret’s.

Golf Clubs

Golf clubs – for so long male bastions, of course – were popular suffragette targets. There are very few examples in Wales. One may well have been here in Newport, where six greens were damaged in August 1913. The trouble is that by now the suffragettes loomed so large in the public consciousness that they were the immediate suspects for this kind of sabotage. The evidence was much stronger here in Pontypool where the words ‘Votes for Women’ were burnt into one of the greens with corrosive liquid and other damage inflicted on the course and pavilion. Nevertheless, the local WSPU branch secretary vehemently denied any knowledge of the incident and insisted that ‘everything that had been done at Panteg had not been done with the sanction of the branch’.

Arson

By 1913 the suffragette campaign had moved on to arson and here we appear to have two failed attempts in the Newport area – one at the Monmouthshire County Council offices and a few weeks later at the new college in Caerleon. Votes for Women literature at the scene suggested the culprits were ‘arsonettes’, as the press now dubbed them.

Who was responsible for these various acts? All the perpetrators went undetected – except for Margaret Mackworth – and her letter-box attack appears to have been a single individual deed on her part. Here she is, writing in her autobiography

‘Various small acts of militancy had been performed by our local branch, but we had not done anything very spectacular or been particularly successful. I decided that we had better try burning letters. . . I had come round to it very reluctantly, partly on “the end justifies the means” principle . . . that it was up to the public to stop us if they really objected, by forcing the Government to give us the vote . . . as secretary of the local Society I felt it my duty to lead off’.

Local activists may have responsible for some of the other attacks, of course. Many years later, the Cardiff suffragette, Edith Lester Jones, a music and drama teacher, admitted to ‘doing a pillar box’ and also trying to set fire to an empty house in the Cyncoed area of Cardiff. But generally the incidents do not appear to have been the work of local militants. More likely, it seems that the culprits were outsiders acting independently or despatched from WSPU headquarters in London to carry out missions in different parts of the country – as in the arson attacks at the time of the National Eisteddfod in Abergavenny in August 1913.

Arrests and imprisonments

‘I can only remember four or five people going to prison from our local branch in all the time we worked together’, wrote Margaret Mackworth. I would say five or six, Margaret. I’ve covered most of these already. There are three members of the Haig family here – at the top, Charlotte Haig, who spent one night in a police cell; so did her sister, Sybil Thomas, at the bottom here; and Margaret Haig Mackworth, who was imprisoned in Usk. Then we have, Olive Fontaine – a month in prison for window smashing. And finally, Bessie Davies and Charlotte Rice imprisoned in November 1911, though I’ve been unable to verify the latter’s Newport connections.

1. Charlotte Haig, arrested 18 November 1910 (‘Black Friday’), London, for obstruction; a night in a police cell before being released with a caution.

2. Bessie Davies; arrested 21 November 1911, London, for trying to break through a police cordon and striking a constable; fined 7s, or 7 days imprisonment.

3. Charlotte Rice, arrested 21 November 1911, London, for trying to break through a police cordon; fined 5s, or 5 days imprisonment.

4. Olive Fontaine, arrested 4 March 1912, London, for smashing a window in Marlborough Road Police Station; one month’s imprisonment with hard labour, Holloway Gaol.

5. Margaret Mackworth, arrested 26 June 1913, Newport, for ‘unlawfully placing an explosive substance in a post office letter box; £10 fine; one month imprisonment in Usk Gaol, after refusal to pay the fine.

6. Sybil Thomas, arrested 24 February 1914, London, for resisting the police in Parliament Square; a night in a police cell before being bound over to keep the peace on payment of £5; refused – sentenced to one day’s imprisonment and thus released.

Census resistance meetings

One reasonable test of how militant the Newport suffragettes were seems to me to be whether or not they boycotted the 1911 census. This test is by no means watertight because there were undoubtedly varying personal pressures on individuals to comply with the census. Nevertheless, boycotting the census would constitute the mildest form of law breaking – militant but non-violent protest, as espoused by a breakaway organisation from the WSPU, the Women’s Freedom League.

The League – which had no branch society in Newport – sent down one of its organisers, Anna Munro, to drum up support for the boycott and this public meeting was held. ‘No votes for women, no information from women’, she told her audience. ‘If they did not count, they were not going to be counted.’ The WSPU leadership also strongly advocated boycott and here we have Annie Kenney urging Newport members to do so. At the following week’s branch meeting, Margaret Mackworth spoke in similar fashion.

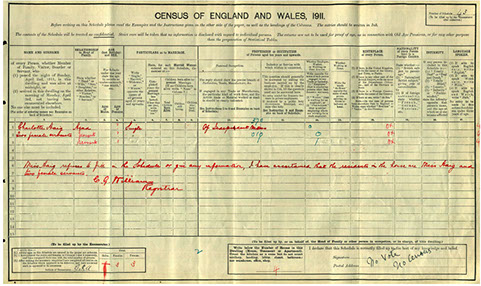

Charlotte Haig’s census form

For those determined on participating in the boycott, the choice was either to flagrantly resist or secretly evade, that is not to be at home on census night. In Wales as a whole, just three women openly refused to fill in the census schedule. One of these was Charlotte Haig who wrote only four words on her form – ‘No Vote, No Census’. The registrar has subsequently added: ‘Miss Haig refuses to fill in the Schedule or give any information’. This means that he has established that three people normally resided in the house. But evidently a number of local census evaders were hidden away there that night – something that occurred in various locations around the country

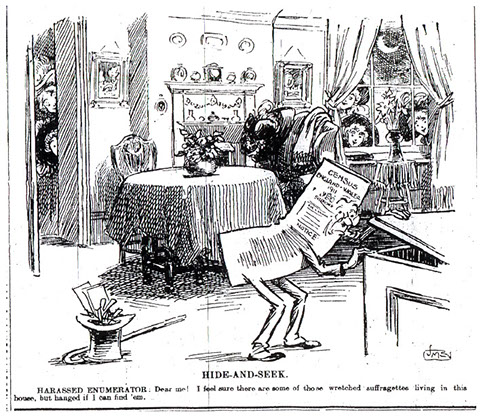

[– portrayed here in a game of ‘Hide-And-Seek’ by the Western Mail’s celebrated cartoonist, J. M. Staniforth. (Caption reads " HARASSED ENUMERATOR: “Dear me! I feel sure there are some of those wretched suffragettes living in this house, but hanged if I can find ‘em.”

[– portrayed here in a game of ‘Hide-And-Seek’ by the Western Mail’s celebrated cartoonist, J. M. Staniforth. (Caption reads " HARASSED ENUMERATOR: “Dear me! I feel sure there are some of those wretched suffragettes living in this house, but hanged if I can find ‘em.”

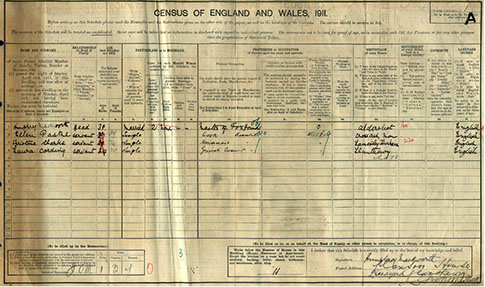

Early the following morning a group of evaders drove around Newport in a motor car decorated with ‘No Vote, No Census’ placards. The most likely figure behind this escapade was Margaret Mackworth, herself a good example of the ‘missing wife’ in the 1911 census. Here we see her husband [Occupation – ‘Master of Fox Hounds’] and three servants recorded in the marital home and Margaret nowhere to be found in the schedules.

Presumably, Margaret spent the night at her aunt’s cottage but how many others did so? The local WSPU leadership spoke of ‘a goodly gathering’ and the house ‘quite crowded out’, with ‘those participating in the boycott being members from Newport, Caerleon, Llantarnam, Llangibby, and Caldicot’. I can identify some – several in Newport, such as Olive Fontaine and Evelyn Lawton; from Llangibby, the vicar’s daughter, Eileen Addams-Williams; a doctor’s wife and sister – Annie and Louisa Corben – from Caldicot. Margaret Mackworth’s school and life-long friend, Edith Pridden (‘Prid’), now a teacher in Bournemouth but a frequent visitor and speaker at Newport suffrage meetings may well have evaded here too. Sybil Thomas – a likely evader – appears to have been in America at the time.

But beyond these, it is hard to identify names of evaders. Indeed, a string of prominent Newport WSPU members complied with the census – including stalwarts like Edith Pilliner, treasurer of the branch, a regular speaker at meetings and a staunch defender of militant tactics – though as the wife of a magistrate, personal circumstances were no doubt difficult. My guess is that there were no more than a dozen evaders from Newport and elsewhere in Charlotte Haig’s cottage on census night – scarcely evidence of fervent local militancy.

Against Votes for Women meeting

The WSPU branch was just one contributor to a vigorous suffrage debate taking place in Newport in the years immediately before the First World War. There were two other major strands. The public meetings here – afternoon and evening – mark the formation of a local organisation against votes for women in Newport in April 1909. ‘What lady would not defend the dignity of her sex and show her disapproval of the suffragette party who thus brought discredit on womanhood?’ declared the president of the Newport branch of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League, Georgiana Rolls, Baroness Llangattock of The Hendre, near Monmouth.

Newport emerged as the strongest and most energetic anti-suffragist society in Wales. It was active for more than five years, from 1909 to 1914, holding meetings and social gatherings, organising petitions, canvassing the public and lobbying parliamentary candidates. Several local women emerged as prominent activists and speakers – including Lady Llangattock, Alice Biddle, wife of the printer here, and Miss Prothero of Malpas Court – that is, Margaret Prothero, the great granddaughter of Thomas Prothero, the arch-enemy of John Frost and the Chartists three generations earlier.

Slide 27: NUWSS

From March 1911, Newport also had a branch of the law-abiding National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, which quickly became a much larger organisation than the WSPU branch in the town.

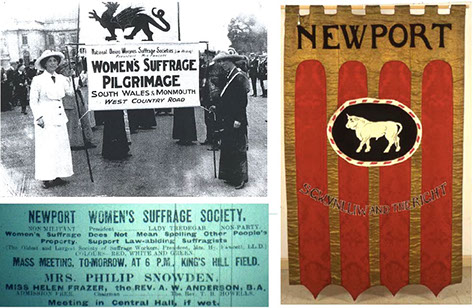

The photograph above shows one of the NUWSS’s most successful enterprises – a ‘pilgrimage’ from all parts of the country to London. The South Wales contingent is about to set off from Cardiff, arriving in Newport later in the day, where a mass open-air meeting was held. Note that the newspaper advertisement reads: ‘Women’s Suffrage Does Not Mean Spoiling Other People’s Property. Support Law-Abiding Suffragists’. This meeting took place the day after Margaret Mackworth’s conviction and imprisonment – accordingly, speakers forcefully condemned ‘suffragette criminal behaviour’, which, they insisted, was ‘alienating hundreds of thousands of supporters and sympathisers’. Note too that the NUWSS is described here as ‘The Oldest and Largest Society of Suffrage Workers’. And indeed it is important to emphasise that by this time it had 450 branches, organised into sixteen regional federations, thereby dwarfing the WSPU.

The photograph above shows one of the NUWSS’s most successful enterprises – a ‘pilgrimage’ from all parts of the country to London. The South Wales contingent is about to set off from Cardiff, arriving in Newport later in the day, where a mass open-air meeting was held. Note that the newspaper advertisement reads: ‘Women’s Suffrage Does Not Mean Spoiling Other People’s Property. Support Law-Abiding Suffragists’. This meeting took place the day after Margaret Mackworth’s conviction and imprisonment – accordingly, speakers forcefully condemned ‘suffragette criminal behaviour’, which, they insisted, was ‘alienating hundreds of thousands of supporters and sympathisers’. Note too that the NUWSS is described here as ‘The Oldest and Largest Society of Suffrage Workers’. And indeed it is important to emphasise that by this time it had 450 branches, organised into sixteen regional federations, thereby dwarfing the WSPU.

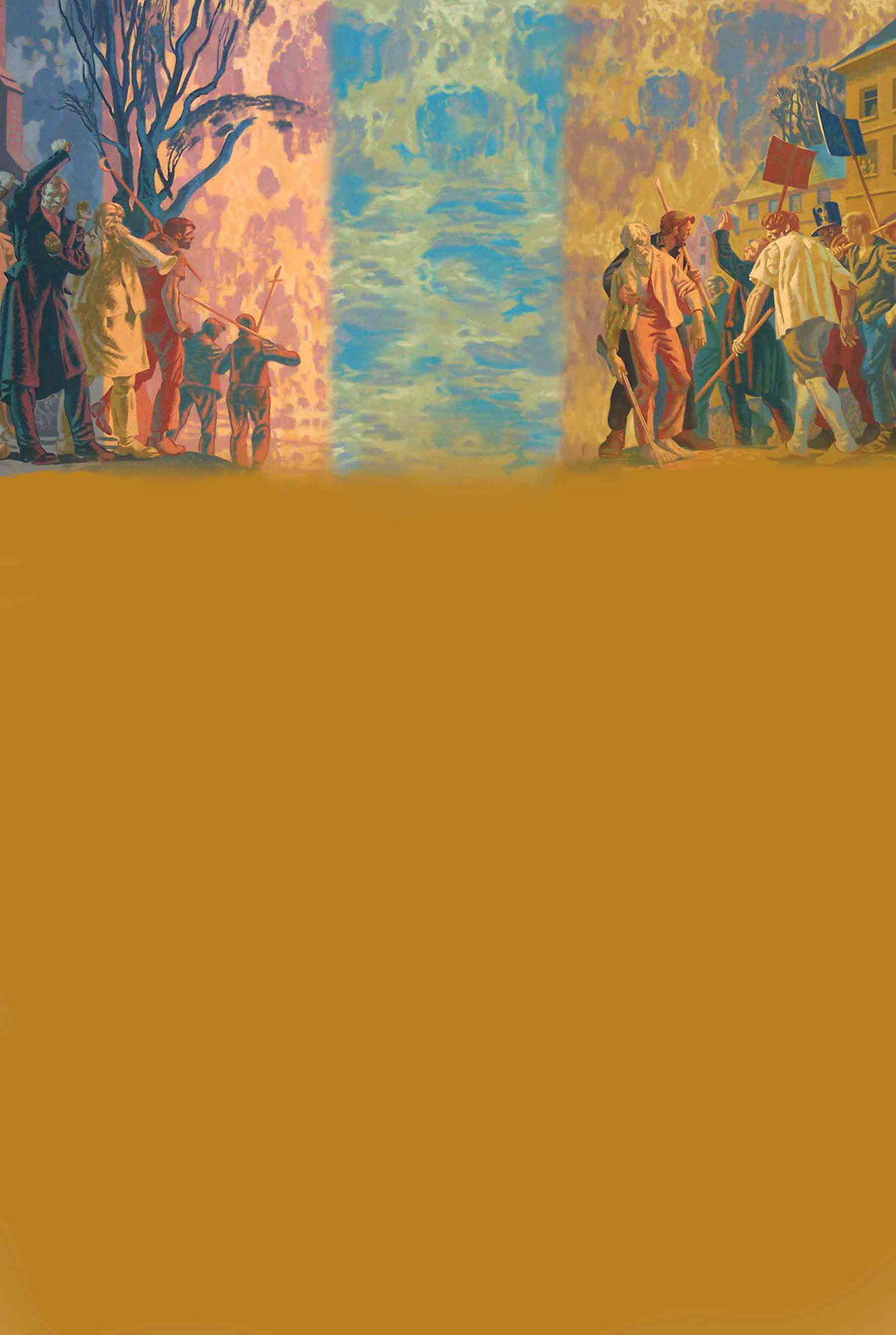

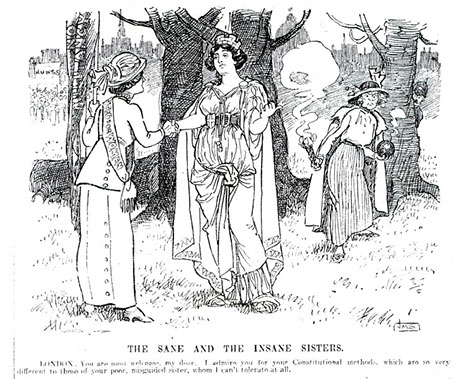

J. M. Staniforth cartoon:

‘The Sane and the Insane Sisters’

I end with another Western Mail cartoon. By 1913 – in terms of leadership strategy – there was indeed a deep division between the emphatically law-abiding suffragists of the NUWSS and the law-breaking deeds of the suffragettes of the WSPU. The ‘sisters’ here have the same aim but they are poles apart in temperament and conduct. On the left, we have an orderly NUWSS procession and a thoroughly ladylike figure with her neat ‘votes for women’ sash and ‘no militancy’ banner. On the right, we have the hysterical, frenzied suffragette – a bomb in one hand and a lit torch in the other – a fearful policeman cowers behind a tree. Thus they are ‘The Sane and the Insane Sisters’ with the caption reading: ‘You are most welcome dear. I admire you for your Constitutional methods, which are so different from those of your poor, misguided sister who I can’t tolerate at all.’ And this is how the suffragettes were widely portrayed by 1913 – in the words of a Western Mail editorial, they were ‘the shriekers, the raiders and the martyrs'.

What I have sought to argue this afternoon is that being a suffragette was broad-ranging and multi-dimensional. Law breaking was not a requirement of WSPU membership. Time and again, speakers at Newport branch meetings voiced these kinds of sentiments: ‘If they did not all want to be militants they could help in many other ways to advance the movement.’ Or, referring to Olive Fontaine and other imprisoned window smashers: ‘Everyone must admire the self-sacrifice and the splendid spirit these women have shown, even if they did not agree with their tactics’. Thus, it seems to me, that we ought to distinguish between ‘suffragettes’ and ‘militant suffragettes’. Most local suffragettes – that is, members of Mrs Pankhurst’s WSPU – did not engage in illegal or violent action. They were able to find their own type and degree of commitment to the cause and thus branches like Newport embraced women of varying persuasions. ‘No one should criticise anyone else’s methods’, insisted Sybil Thomas, ‘it is up to each individual activist’.

Whatever their personal views and reservations about window smashing and other forms of law breaking, the suffragettes of Newport and elsewhere promoted their cause with great endeavour, commitment and zeal, driven by a deep sense of righteousness and fired by what they saw as the repeated injustices of a dishonest, disingenuous government towards women.

The suffragettes generally, and certainly here in Newport, were not the insane, lunatic fringe of the women’s suffrage movement. Rather, they were women of ability and passion, resilience and courage.